Pakistan’s ‘America Problem’ Is Not Going Anywhere

Washington has been unable to address a series of troubles that it created for itself when it fractured its ties with Islamabad. This became a precursor to its shameful flight from Afghanistan.

Months after President Joe Biden announced the complete, irreversible, and long-awaited withdrawal of U.S. forces from Afghanistan, the last contingent of U.S. troops left Kabul. This safe exit was facilitated through a cooperative arrangement between Washington and the Afghan Taliban, a group that the former had uprooted in 2001 and fought against ever since. That the United States has left Afghanistan at the Taliban’s mercy is reflective of how badly it failed in stopping the insurgent group from reclaiming what it had lost due to Operation Enduring Freedom: absolute control of Afghanistan. The abject U.S. failure to prevent the Taliban from staging a comeback, according to many, is but a result of Pakistan’s unsubstantiated, unflinching espousal of its “strategic asset and proxy” in the Afghan Taliban. Daniel Markey noted in an op-ed published by Foreign Affairs that “the Taliban would not exist today without Pakistan’s support.” Markey’s argument is not new. For Washington, Islamabad’s so-called, highly-touted duplicity had impeded its entire gambit and schemas for Kabul. Islamabad, on the other hand, took and continues to take exceptions to these allegations. Also, it looks askance at attempts to scapegoat it for the turmoil in Afghanistan. Instead, Pakistan has been grappling with its America problem for the past two decades. Washington has been unable to address a series of troubles that it created for itself when it fractured its ties with Islamabad. This became a precursor to its shameful flight from Afghanistan. There are two elements that have gone on to craft Pakistan’s perennial America problem.

Do More, Advise Less

Following the 9/11 attacks, Pakistan became a willing, frontline ally in the U.S.-led Global War on Terror. The decision proved costly, for the country lost both men and material and has still not fully recovered from the deleterious ramifications of the ensuing spate of terrorism. Much of what Pakistan went through was a direct result of ruckus and mayhem in Afghanistan. For its part, Pakistan did try to persuade the United States to not invade Afghanistan, not lump together the Taliban and Al Qaeda, and diplomatically engage with the Taliban. But the United States, despite early overtures from the Taliban, would not have any of it. Washington not only scoffed at Islamabad’s counsel but also ascribed the negative fallout of its military-centric policy to Pakistan allegedly not doing enough.

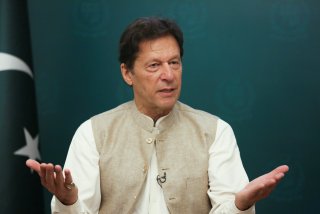

Pakistan’s Prime Minister Imran Khan claims that the United States accusing Pakistan of playing a double game, despite the latter having made meritorious sacrifices in a war it had nothing to do with, marked the worst phase of Pakistani-U.S. relations. The do-more mantra, coupled with its continued reticence to take Pakistan’s peace plans seriously, became a major stumbling block in bilateral relations. However, on the back of engagements at the highest levels, Washington agreed to substantively engage with the Afghan Taliban in a dialogue process that Islamabad facilitated. While Islamabad welcomed the Doha deal that was signed between Washington and the Taliban, it warned Washington against withdrawing without achieving progress towards establishing an inclusive political settlement in Afghanistan. However, rather than pay heed to seemingly practical advice, the United States left hastily. What’s more, U.S. interlocutors continue expecting Pakistan to do the heavy lifting in Afghanistan, even after the United States is gone.

Sovereignty, India, and China

In a 2011 appearance in BBC HARDtalk, Khan flayed the United States for conducting the airstrikes in Abbottabad that killed Osama bin Laden. He described the act as an indication of how Washington disrespected Islamabad. Khan posed the question: Does the Pakistani government not have any semblance of sovereignty? He vowed to fight the war on terror as prime minister without being perceived as a lackey of the United States. Even today, the sovereignty issue dictates Khan’s policy positions on the United States; Pakistani-U.S. relations continue to be strained over Washington’s utter disregard for Islamabad’s territorial integrity. An unremitting drone campaign, the Raymond Davis saga, the Abbottabad raid, and the brazen kinetic action against Pakistani soldiers in Salala, were clear examples of how the United States did not respect the sovereignty of a country it called an ally.

All this is coupled with Washington’s growing strategic bonhomie with New Delhi. The United States has propped up India through a flurry of defense deals, including a nuclear deal that jeopardizes its non-proliferation and strategic stability-related goals in the region and beyond. Not only have these U.S. weapons and surveillance capabilities emboldened an even otherwise risk-acceptant India, but they have also damaged the United States’ credibility and leverage to act as an effective mediator. It is expected that the United States might turn the other way should India launch kinetic actions against Pakistan while also pressuring the latter to stand down. While the United States won’t be offering carrots, it will certainly be willing to use sticks against Pakistan going forward. In effect, the United States could just ratify actions that harm the prospect of maintaining strategic stability in South Asia.

Another factor that adds to the already complex relationship is Pakistan’s burgeoning strategic partnership with China. The Sino-U.S. rivalry has had an effect on Pakistan given that the United States has openly expressed its misgivings about the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). That Pakistan is committed to enhancing its economic security profile is reason enough for it to take enunciations against CPEC as veiled threats to its sovereignty. Also, the Sino-Pak concert may not please the United States due to both countries’ openness to engaging with a Taliban-led Afghanistan. Rabia Akhtar recently drew attention to China’s positive outlook on the developments in Afghanistan. “China’s impact on regional stability is not to be underestimated and while Beijing would like to fill the political vacuum created by the US retreat, it is also poised to assume a leadership role in bringing its current and prospective Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) member countries in the region together on one platform to realize its South Asian economic ambitions,” Akhtar said in a short analysis posted on the Atlantic Council’s website.

While this will indeed open avenues for regional connectivity, it will give China much more space and say in the region, something which is not in the United States’ national interest. Pakistan, by virtue of being China’s junior and most important regional partner, will be in the thick of things.

All this, coupled with the lack of appetite in Washington to recalibrate its ties with Islamabad, means that the United States will have more freedom to pin down Pakistan on many issues. The safety and security of Pakistan’s nuclear weapons could be one of the issues that could yet again become a bone of contention between the two countries. Next, the United States could increase its criticisms of Pakistan over its alleged support to terror outfits, lack of media freedoms, and other anomalies. The United States could then be expected to tighten the noose around Pakistan by influencing international organizations like the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank.

While Pakistan has time and again expressed its desire to broaden the scope of its ties with the United States, the latter’s lackadaisical approach has further aggravated Pakistan’s worries when it comes to bilateral relations. The U.S. bid to have stable and productive relations with Pakistan has and is not supplemented by actions required to achieve them. Pakistan has tried incessantly to set the record straight, dispel many a wrong impression, and actually support the United States. However, it has been unable to evade America’s attitudinal biases and structural barriers. Pakistan’s America problem is not likely to dissipate anytime soon.

Syed Ali Zia Jaffery is Research Associate, Center for Security, Strategy and Policy Research (CSSPR), University of Lahore.

Image: Reuters