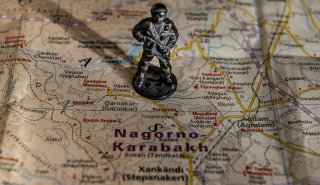

Russia’s Last Stand in the Caucasus Is Over

Does this remove a roadblock to peace?

With the war in Ukraine in its second year, it is easy to pass over the fact that in other parts of the former Soviet Union conflict, both hot and cold, has been ongoing since the early 1990s, mostly at Russia’s instigation. By exploiting a string of unrecognized states and provinces Moscow has maintained influence in its so-called “near abroad” for a generation after its empire’s collapse.

But, like Ernest Hemmingway’s quote on bankruptcy, the end has been coming first gradually, then suddenly. Russia’s geopolitical insolvency, actual but almost inconspicuous for a generation, is now emphatically laid bare everywhere, and Ukraine has been the catalyst.

The ouster late last month of Russian oligarch Ruben Vardanyan as state minister of the contested territory of Karabakh in the South Caucasus is the latest, startling demonstration of Russia’s departure from the scene. Parachuted to the region in November to stabilize the Kremlin’s crumbling control over the Armenian separatist-run enclave within Azerbaijan, the removal of Vardanyan will likely presage a peace agreement that has eluded the region for decades, precisely because it has been against Russian interests to advance one.

Just how fast Moscow’s great power shrinkage has accelerated in a region such as the Caucasus is stark. Merely two years ago Russia seemingly bestrode the place, single-handedly negotiating a ceasefire agreement in 2020 between ex-Soviet states Azerbaijan and Armenia following their vicious forty-four-day war. A U.S. attempt to end the conflict had fizzled; European Union efforts seemed supine. It was in Moscow with Vladimir Putin present that the leaders of both combatant countries signed the deal. In a shock to international observers, they even consented to Russian peacekeepers in Karabakh. This represented the first Russian boots on Azerbaijani soil since Soviet times.

Despite a five-year remit, Russia’s new military presence smelled permanent; but in the last twelve months that near-certainty has vanished. Armenian-Azerbaijan border skirmishes with the worse casualties since 2020 were not halted by Russian peacekeepers but rather by American pressure. The European Union has done the heavy lifting on peace talks, with negotiators reaching further and faster than ever before on interminable issues, from border demarcation to the exchange of landmine maps for prisoners. Most important of all, the EU has made headway in facilitating the first-ever direct talks between Azerbaijan and the Armenian separatists, paving the way to a potential agreement hinged around an enhanced minority status within a sovereign Azerbaijan.

With Russia becoming a bystander, Vardanyan was exported from Moscow to shake the tree. Installed as Karabakh “state minister” over the heads of the Armenian government, the traditional guiding hand of separatist politics, Vardanyan spoke openly of fighting Azerbaijan, waged a public war of words with the Armenian prime minister, and raised the stakes by opening gold mines in the territory and exporting their contents. Some of his supporters in the Karabakh “parliament” even called for the enclave to become a territory of the Russian Federation. The intention so clearly was to fan flames that only the Kremlin would then be able to extinguish.

At any other point over the last thirty years, the imposition on the Karabakh political scene of this Armenian-born businessman—who made billions in Russia, where he had lived since 1985—might have stuck. But at no other point in those thirty years would it have been necessary for Russia to place one of their own into this position to maintain influence. Evaporating fear of Moscow’s power, so clearly wanting in Ukraine, made it necessary for an intervention while at the same time removing its effectiveness.

Vardanyan’s fall is proof of the region’s liberation from Moscow’s oversight. The oligarch’s role triggered previously unthinkable criticism of Russia from both Armenian and Azerbaijani leaders at last month’s Munich Security Conference. “Ask him, ‘Who sent you to Karabakh and why? Why did you cause a split within the Karabakh authorities [with the Armenian government]?’ Of course, the Russians sent him. Who else could send him?” said Gagik Melkonian, a senior advisor to Armenia’s prime minister Nikol Pashinyan. The day before, Azerbaijani president Ilham Aliyev said at the Conference: “We are ready to start practical communications with Karabakh’s Armenian community…But we can only move forward with it when Ruben Vardanyan, a Russian citizen, organized crime oligarch, and a person who laundered money in Europe, leaves your territory.”

Now, Vardanyan is out, and peace talks will resume. The chances of Russia’s peacekeepers lasting beyond the remainder of their five-year mandate look vanishingly slim. Armenians are considering the previously unspeakable, even of cutting off Russian energy supplies and connecting with those of their petrostate former archenemy Azerbaijan. Azerbaijanis are speaking of reconciliation with those who they allege committed war crimes against them a generation ago.

None of this would surely be happening had Moscow been able to sustain its regional deep freeze. But it could not. Now, with Russia’s last stand in the Caucasus over, a roadblock to peace is removed. The signs of the thaw are everywhere.

Mat Whatley is a British army veteran. He is also the former head of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) in Donetsk, Ukraine, the EU Monitoring Mission in Georgia, and an OSCE spokesman in former Yugoslavia.

Image: Pavel Byrkin/Shutterstock.