A Russian Perspective On Foreign Affairs: An Interview with Konstantin Zatulin

Is Vladimir Putin truly on a mission to resurrect the Russian empire or the Soviet Union?

President Vladimir Putin’s 2005 statement that the collapse of the Soviet Union “was the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century” led to accusations that the Russian leader harbored imperial aspirations. Russia’s actions since then, including the seizure of Crimea in 2014 and fomenting of warfare in eastern Ukraine, have only heightened scrutiny of its aspirations abroad.

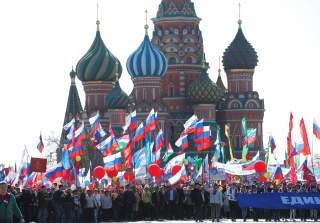

Is Putin truly on a mission to resurrect the Russian empire or Soviet Union? To obtain a better understanding of Russia’s foreign-policy goals, the National Interest spoke with Konstantin Zatulin, first deputy chairman of the Duma’s committee for relations with the CIS and Russians nationals abroad, for nearly an hour on July 23 in his Moscow office at the Institute for the Countries of CIS, which Zatulin directs in addition to his role in the Russian parliament. Zatulin is a leading figure in Putin’s United Russia party and is regarded as one of the government’s foremost experts on the Russian “near abroad.” He presented an assessment of Russian foreign policy that is quite different from the one that is often held by the West and by many of Russia’s neighbors.

From the outset, Zatulin dismissed the notion that Putin holds ambitions of major territorial conquest. The Russian president, he said, “is a person living in real time and who understands well that whatever our personal feelings, opinions, and assessments might be, restoring the Russian empire or the Soviet Union is impossible because they are in the past.” While Russia may have serious issues with some of its neighbors like the Baltic states, a move to invade them “is completely beyond the realm of common sense.” Zatulin argued that a policy of territorial conquest is totally unnecessary. He contended that Russia is a “self-sufficient nation” which has all the necessary assets “to be confident in her ability to build her own future” and not feel “critically dependent on relations with other governments.”

At the same time, Russia has no interest in being just another country. Zatulin explained that Russia aspires to have greater sway over global affairs. “If by the restoration of the Russian empire, one means restoring the big role that the Russian empire or the Soviet Union played in international life, then we would of course be happy to have such a role today,” he stated. The Russian lawmaker asserted that such a desire is in no way unusual or nefarious, claiming “if we are being honest, all the other key players in the international process are striving for the same thing.” Thus, he views accusations that Russia behaves like a rogue state as unfounded.

Zatulin charged that the leadership in many former Soviet republics exaggerated the threat posed by Russia for political reasons. Political elites in those countries, he insists, use Russia as a bogeyman to distract disgruntled citizens from internal problems. Moreover, Zatulin said that Russia’s neighbors want to draw the West into a conflict with Moscow. “Of course local politicians want to make their problems NATO’s problems. They really want someone to fight with Russia on their behalf,” he contended.

Western policymakers and experts almost uniformly view the annexation of Crimea as a violation of Ukraine’s sovereignty. However, Zatulin maintained that Russia’s recognition of Crimea as part of Ukraine was never unconditional. Referencing the 1997 Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Partnership between the two countries, he argued that Russia’s pledge to not challenge the status of Crimea was contingent on good relations with Kiev. “We accepted these borders under the condition that we have friendship, cooperation, and partnership with Ukraine. But as soon as Ukraine signed this treaty, it immediately started asking to join NATO,” he said. According to him, even during the Yeltsin administration, Russian leadership was so displeased with Ukraine’s behavior that it threatened to declare the deal void.

The Russian lawmaker also accused the Ukrainian government of pursuing a long-standing policy of discrimination against ethnic Russians and Russian speakers in the country. Zatulin blamed the decline of the Russian population’s size in Ukraine on a “process of assimilation” aimed at creating a hostile environment in which “Russians do not feel comfortable to be considered as Russians, so they pretend to be Ukrainians instead.” The resulting tension backlash from Russians in Ukraine ultimately “detonated the events in Crimea in 2014.” In this way, Zatulin contends the Ukrainian government brought about the loss of Crimea and the current civil war in the Donbass on itself. This is more than a general observation. Instead Zatulin’s statements indicate the Moscow is likely to insist on significant concessions for the Russian speaking population in Donetsk and Luhansk before agreeing to return those regions to Ukraine.

Unease about NATO enlargement remains at the forefront of Russian foreign policy decision-making. Citing NATO’s 1999 bombing of Yugoslavia, Zatulin challenged the claim that the alliance is merely a defensive coalition. From Russia’s perspective, NATO is without a question an organization with offensive military capability and intent. Subsequently, Moscow “cannot be happy about seeing a military-political bloc that has a much mightier military potential than the Russian federation alone move ever closer to our borders.”

Anxiety over NATO expansion is exacerbated by Russia’s history of invasions from the West. Pointing to attacks from the Swedish empire, Napoleonic France, and Nazi Germany, Zatulin concluded, “Clearly, our historical experience tells us that we must be concerned with our security, and we are concerned about it.”

Zatulin argued that Ukraine and Georgia at this moment in time are de facto members of NATO. The Russian parliamentarian noted that the two former Soviet republics participate in joint maneuvers with NATO, send officers from their armed forces to study in NATO colleges, and receive logistical support from alliance members. “They essentially are in NATO. The only thing they lack is official legitimation of their membership,” he said.

Nevertheless, Russia would still retaliate if Ukraine or Georgia were to formally join the alliance. Zatulin warned that such a development “would undoubtedly mean a confrontation between Russia and the governments of NATO.” Further NATO expansion would also incentivize Moscow to continue deepening cooperation with Beijing to counterbalance the West. “The United States, with its missionary zeal, extreme behavior, and reckless positioning pushes Russia into ever tighter relations with China,” Zatulin said.

Moscow’s relations with many of its neighbors are clearly strained. At the core of this tension is the prospect of former Soviet republics aligning ever more closely with the West. Russia views this development as a dangerous opportunity for Russia’s geopolitical rivals to encircle it and for its ex-territories to settle old scores while hiding behind the West’s military umbrella. But for these newly independent state, like Ukraine and Georgia, moving into the NATO orbit is viewed as a manifestation of their sovereignty and requirement for their security. For now, there is no sign of the mutual distrust between Russia and its former territories subsiding any time soon.

Dimitri Alexander Simes is a reporter-intern at the National Interest.