The House That Stalin Built

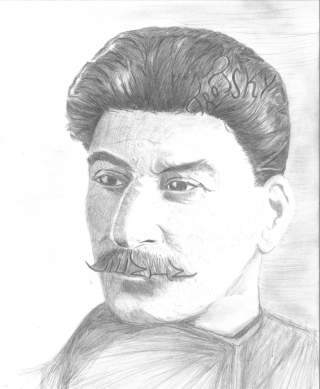

Stephen Kotkin’s meticulous biography of Joseph Stalin dispenses with the myth that he was an intellectual dullard, showing that he was quite shrewd as well as forceful.

Some of the conditions that helped lead to Ukraine’s current fractured state were created during and after World War II, when Stalin attached large portions of eastern Poland and smaller portions of eastern Czechoslovakia and Romania to Ukraine. (He was not responsible, however, for transferring Crimea to Kiev’s jurisdiction. That happened after Stalin died, when Nikita Khrushchev was in control of the Communist Party.) As in the 1920s, borders were drawn or changed to suit Moscow’s convenience, without consultation with the residents or their consent. Nevertheless, when the Soviet Union collapsed, what had been local administrative boundaries became international frontiers overnight.

IN ASSESSING Stalin’s character, Kotkin rejects both Trotsky’s view (that Stalin was a plodding, second-rate apparatchik) and the psychological interpretation that attributes Stalin’s behavior as an adult to his reaction to abuse he experienced as a child. In fact, Kotkin argues, Stalin was hardworking, a prolific journalist and propagandist, with a knack for getting things done and political skills far superior to Trotsky’s. Nor were his childhood experiences any more trying than those of other Georgian students in Tbilisi’s Russian Orthodox seminary, many of whom became Mensheviks.

Stalin’s battle against Trotsky began in 1917, and the fallout from Lenin’s “Testament” (which purported to recommend that Stalin be replaced as the party’s general secretary) haunted him in his subsequent struggle with Lev Kamenev, Grigory Zinoviev and Nikolai Bukharin. One of the most valuable features of Kotkin’s study is his acute analysis of the Lenin “Testament.” There are reasons to suspect its authenticity. This paper with “a few typed lines, no signature, no identifying initials” surfaced after the Twelfth Party Congress in April 1923—several months after Lenin died. There is no record of it in the logs kept of Lenin’s dictation. Lenin’s widow, Nadezhda Krupskaya, had a legitimate grudge against Stalin and cooperated with Trotsky to spread the “Testament” initially. But Krupskaya was the only person, aside from his physicians, who saw Lenin regularly following his incapacitation. Lenin may well have expressed similar thoughts to her, perhaps in response to her complaints about Stalin’s behavior.

Whether the “Testament” was authentic or not, Stalin managed to neutralize its impact by maneuvering to prevent anyone else from taking advantage of it. Put bluntly, Trotsky’s political skills were no match for Stalin’s. He famously wrote, “Stalin did not create the apparatus. The apparatus created him.” This was wrong. Stalin’s construction of a Soviet apparatus, Kotkin says, “was a colossal feat.” Kotkin adds, “He demonstrated surpassing organizational abilities, a mammoth appetite for work, a strategic mind, and an unscrupulousness that recalled his master teacher, Lenin.” When Lenin appointed Stalin general secretary in 1922, he had, more or less, handed him the keys to the Bolshevik kingdom. Stalin immediately began to construct a personal dictatorship within a dictatorship.

In a marvelous set piece, Kotkin vividly describes Trotsky’s internal exile in January 1928, which coincided with the expulsion of several dozen other “bawlers and neurasthenics of the Left,” as Stalin dubbed them. Trotsky himself was trundled out of his Moscow apartment by Stalin’s goons. He wore a fur coat over pajamas and socks as he was brought to the train station where a single rail coach with him, his family members and a secret police convoy left Moscow. After he arrived at the last station on the Central Asian rail line, Kotkin writes, “a bus laden with the luggage hauled them the final 150 miles across snowy mountains, and arrived in Alma-Ata at 3:00 a.m. on January 25. He and family were billeted at the Hotel Seven Rivers on—what else—Gogol Street.”

It was merely the first in a series of crushing blows that Stalin would deal to the old Bolsheviks. Overall, his character was filled with traits usually considered contradictory. He was, in Kotkin’s words, “Closed and gregarious, vindictive and solicitous,” “an ideologue who was flexibly pragmatic” and “a precocious geostrategic thinker . . . who was, however, prone to egregious strategic blunders.” The contrasting features of the old boy’s character echo George Kennan’s observation that if one is confronted with contradictory statements about Russia, the wisest assumption is that both are true.

In 1928, Stalin was poised to launch a massive program of forced collectivization, creating a human catastrophe that transformed the Soviet Union. If Stalin had not lived to carry it through, Kotkin is convinced, and is convincing in his arguments, then no other Bolshevik leader would have done so. “More than almost any other great man in history,” wrote the British historian E. H. Carr, “Stalin illustrates the thesis that circumstances make the man, not the man the circumstances.” Not so. In human history, individual leaders matter. Kotkin’s work, the first of a projected trilogy, shows why.

Jack F. Matlock Jr. is a former professor at the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton and a former U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union.

Image: Rebecca M. Miller