The Middle East's Conflicts Are About Religion

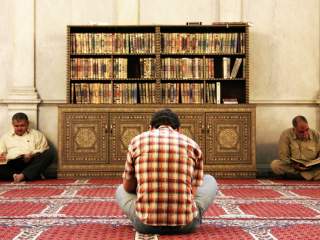

Piety—not just power—remains a driving force in the region.

A meme is gaining traction within American government and media, and it goes like this: The conflicts of the Middle East aren’t about religion. Jihadist violence? Garden-variety criminality, the president says. Young people flocking to ISIS? “Thrill-seekers,” posits the secretary of state, who are desperate for “jobs,” per a State Department spokeswoman. Iran’s belligerence? A reaction to ostracization, a former embassy hostage insists. Sunni-Shiite bloodletting? Jockeying for power, the pundits conclude.

It’s not just a false narrative, but a dangerous one. It’s true that the Middle East offers no easy policy options: witness Syria, where the choice of sovereign increasingly appears to be between the Islamic State and Islamic Republic (but neither of which, we’re told, takes Islam all that seriously). Still, if we’re to even try to address the region’s maladies, we have to first correctly diagnose its disease.

It’s not that religion is the only force at play. It’s not that the ranks of jihadist groups don’t also include common criminals, or that leaders never use religion to their own cynical ends (Saddam Hussein’s Faith Campaign is one salient example). It’s that these phenomena are relatively minor compared to the vast influence religious belief still wields across much of the Middle East and the broader Islamic world.

It is, of course, near impossible to empirically demonstrate the motivations behind human actions, whether individual or collective. That doesn’t mean, however, that our only recourse is to project our own motivations onto societies for which they don’t fit. The debate over the religiosity of groups like ISIS, or of regimes like Saudi Arabia or Iran, is largely confined to the Western chattering classes. In the Islamic Middle East, the influence of faith is more often than not taken as a given.

Polls are instructive. In 2013, Pew—one of the world’s leading pollsters—conducted a survey of thirty-eight thousand people in thirty-nine Muslim-majority countries. The results showed an overwhelming majority backed the implementation of Islamic law, particularly in countries that are some of the primary hubs of terror groups: 99 percent in Afghanistan, for example, and 91 percent in Iraq.

On matters of identity, results have been comparable. In Pew’s 2011 survey, 94 percent of respondents in Pakistan said they identify first as Muslims rather than Pakistanis. In Jordan, a Western-oriented country and close U.S. ally, three times as many identified primarily as Muslims. Even in comparatively secular Turkey (and, incidentally, in the United States), twice as many people identified more as Muslims than citizens of their respective countries.

For most Middle Eastern Muslims, it is a personal and professional third rail to call for the removal of religion from public life, let alone to call into question God’s existence. In Egypt, according to Pew, just 6 percent of respondents said the Quran need not be consulted in drafting laws, while more than eight in ten said those who leave the faith should be stoned to death (the Palestinian Authority, Afghanistan and Pakistan yielded similar results). In these countries at least, the community of secular-minded individuals, let alone atheists, is exceedingly small. Why then we do conclude that it is precisely those most loudly trumpeting their religious convictions who belong to it? I see two factors at play.

First, most post-religious Westerners have never felt the pull of faith. The prospect that a mentally sound person—let alone billions of them—would let spiritual conviction guide their most consequential actions doesn’t quite add up. So too the notion of religion as one’s primary identity marker. We deem one’s nation to be an entirely legitimate identity marker; indeed, it’s the default option, and in this country, failure to take sufficient pride in being American is grounds for suspicion. The prospect that faith, or even membership in a faith community, could fill that role rings hollow.

Second, from a policy perspective, nonreligious motives are more comforting. Addressing terrestrial motivations (money, land, grievance) is far easier than confronting a person’s closest-held beliefs and the immutable scripture that underlies them. That’s particularly the case because scrutinizing specific religious doctrines remains one of the last great taboos, all the more so when the faith in question is the supposedly non-white creed of Islam.

That’s why even when religion is conceded to be at play, the assumption among right-thinking people is that faith is being “twisted” or “used” for some ulterior motive. Rarely considered is the possibility that billions of people take religion seriously and do their best to follow its precepts—precepts that can lead just as easily to charity and loving-kindness as to tribalism and terror.

On January 4, Vox published a lengthy article on the Saudi-Iranian rivalry that concluded, predictably, that “it’s not really about religion.” The very next day, the same author published a similar piece that offered this: “No one who seriously studies the Middle East considers Sunni-Shia sectarianism to be a primarily religious issue.” That article approvingly cited a video by the Washington-based Al Jazeera anchor Mehdi Hasan, asserting that faith-based sectarian conflict is a “myth” and that regional rivalries are actually about “power, not piety.”

It’s particularly rich for Hasan to dismiss the very notion of sectarianism’s sway. In an undated YouTube video (it’s since been scrubbed from the Internet but a description is here), Hasan, who is Shiite, descends into a prolonged, tearful wail when recounting the story of the seventh-century Battle of Karbala, a formative moment in Shiite history in which Muhammad’s grandson Hussain was killed. In another, he describes “kuffar” (non-Muslims) as “cattle. . . animals bending any rule to fulfill any desire” (that video is still online). So much for Hasan’s pieties, as it were, over the power of faith and faction.

Nearly a year ago, Graeme Wood authored an Atlantic cover piece, “What ISIS Really Wants,” propounding the apparently revolutionary notion that the group is driven by genuine religious fervor, and that its fire is based on a literal reading of Islamic texts.

The backlash was swift. In the same outlet, Wood was condemned for demonizing Muslims, and in the New Yorker for playing into the hands of extremists. Last month, responding to the second Vox piece, Wood tweeted: “Thought experiment: if these conflicts *were* about ‘ancient religious hatreds,’ how would they be different?”

It wasn’t so long ago that Westerners took religion seriously. The Crusades, the Inquisition and Europe’s wars of religion were about a lot of things—power, dynastic politics, land—but they were also genuinely, inseparably, fundamentally about religious belief. Barely a century ago, religion guided the lives of Westerners just as it does in much of the Islamic world today. For hundreds of millions in America it still does, and those Americans are rarely the ones asking whether the doctrinal devotion of most ISIS fighters, Saudi sheikhs or Iranian mullahs is a sham.

The rest of us are increasingly expected to nod to certain shibboleths: that power, money, resources and hegemony are the stuff of human motivation and, by extension, of international relations. Belief, after all, isn’t—for the simple reason that it isn’t for us.

Oren Kessler is deputy director for research at Foundation for Defense of Democracies.

Image: Wikimedia Commons / Erik Albers.