Is Trump Pushing China and Japan Together? Not Quite.

Security concerns will remain a barrier to Beijing-Tokyo rapprochement.

Over the past year, Sino-Japanese relations have been experiencing a thaw in their tense relationship. In September 2017, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe made a surprise visit to the Chinese Embassy in Tokyo to mark China’s upcoming National Day and the forty-fifth anniversary of the normalization of Japan-China relations. President Xi Jinping reciprocated Abe’s gesture by refraining from criticizing Japan at the Nanjing Massacre commemorative events in December 2017.

The warming in relations is being driven by uncertainty emanating out of President Donald Trump’s unpredictable policies towards allies and its increasingly hawkish policies on China. For Japan, the withdrawal from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade pact by the Trump administration sent shock waves through Japan’s government offices in Kasumigaseki. This was because the TPP was seen by Tokyo as the economic inculcation of the U.S. economy into the region to match America’s extensive network of alliances and security partnerships that can be found throughout North and Southeast Asia. With the U.S. withdrawal and Trump’s perceived transactional approach to foreign policy, Tokyo was left perplexed about how best to secure its interests in the region and to ensure that the region did not return to a Sino-centric order.

Concerns deepened when the Trump administration slapped steel tariffs on Japan, pressed for a bilateral free-trade agreement and unilaterally stopped joint training with the South Korean military on the peninsula without prior consultation with Tokyo.

Washington’s ire has also unnerved Beijing as the Trump administration has vacillated on issues that are meant to be the cornerstone of Sino-U.S. relations, such as questioning the “One China” policy, in the wake of President Trump’s election. On the one hand, pressure on Beijing to induce North Korea to denuclearize and to lower its belligerence in the region was understandable by leaders in China. On the other hand, Trump’s 180-degree turn towards prosecuting a damaging trade war, labeling China as a strategic competitor, and most recently Vice President Mike Pence’s speech at the Hudson Institute on Chinese influence in the midterm elections has alarmed Beijing.

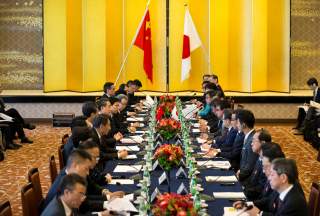

Beijing and Tokyo have responded to the Trump administration’s provocations since his election by trying to resurrect their troubled relationship, starting with a bilateral meeting on October 26, 2018, in Beijing. For Tokyo, these bilateral talks showcase Japan’s commitment to diplomacy, deepen economic engagement with China, and build multilateral trade by accelerating both the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (an alternative to TPP) and trilateral negotiations between for a South Korea, Japan, and China free-trade agreement.

The discussions between Japan and China might also be an opportunity for Tokyo to act as a bridge between the United States and China.

For Beijing, the summit is an attempt to bring some stability to the region after spending considerable political capital attempting to isolate and demonize Japan since the nationalization of the Senkaku Islands in September 2012.

In the same vein, the recent warming of Sino-South Korean relations after Beijing imposed sanctions on Seoul as punishment for deploying America’s Terminal High Altitude Area Defense missile system is an effort by China to mend fences. Ultimately, China hopes to work things out with all its neighbors so that it can concentrate its diplomatic energies on rapidly deteriorating Sino-U.S. relations.

In short, the Trump administration’s eschewing of the American-built liberal world order for a realpolitik, transactional approach to foreign policy has inadvertently provided the foundation for Japan and China to move historical grievances to the wayside and return to their post-normalization dynamic of “hot economics/cold politics” known as Seikei Bunri/ 政経分離 in Japanese.

This characterization is important. At the Russian Federation at the Eastern Economic Forum, where Japan-China held their summit, Abe articulated a return to the normal track of development. Furthermore, he suggested this would reset Japanese-Chinese relations to before the Senkaku Islands—taking Sino-Japanese ties back to the Seikei Bunri dynamic.

Optimists have called the warming as an incremental path towards a “Pax Sinae-Nipponica era.” They have highlighted that Abe and President Xi’s dominant positions within their polities places them in a unique position to advance their national interests through economic cooperation on the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), trade pacts, and developing co-dependence as the Germans and French did to make a future war between them a thing of the past.

This vision is enticing however unrealistic. Whereas a real warming of relations would be welcome in the region, the reality is that the difficult security, economic, and political issues that have divided the two Asia giants remain and they cannot be easily resolved.

For instance on security, lawfare tactics in the East China Sea to erode Japanese sovereignty over the Senkaku Islands are a sign of bad faith in any warming of relations. The same could be said for the militarization of human-made islands in the South China Sea and the rejection of the Permanent Court of Arbitration’s July 2016 decision against all of China’s claims in the South China Sea.

Japan does not help its own case against China’s artificial island claims when it is building artificial islands as well such as Okinotorishima. This inconsistent position sends the message to Beijing that Japan’s position is hypocritical and not wedded to any legal interpretation—only national interests.

Beijing’s concerns also stem from Abe’s leadership on the Free and Open Indo-Pacific (FOIP) Strategy and its sponsoring of counter-initiatives to the BRI such as the Asian-Africa Growth Corridor. Both initiatives push back against President Xi’s signature policy—the BRI—and are evidence that the leaders have different visions of the region’s future integration. Saliently, their normative nature suggests that Xi’s proposals are neither free nor open and thus inimical to states that China is promoting its keynote diplomatic initiatives such as Community of Common Destiny for Mankind.

While Trump's realpolitik foreign policy has created political space for Sino-Japanese relations to re-engage at the level of their top leadership, security remains a major stumbling block between the two neighbors that cannot be addressed in a single summit. Both leaders will need to build deeper and broader trust in their relationship.

Judging by the recent United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement’s Article 32.10 that limits Canada, Mexico and America from entering into a free-trade agreement with a “nonmarket” economy (read China), the Sino-Japanese thaw is likely to be ephemeral as any bilateral free-trade agreement between Japan and America is likely to have a similar demand from U.S. counterparts.

Lastly, the intensifying security competition between China and the United States will also place greater political, economic and military demands on Japan. This will complicate the transient warming of Sino-Japanese relations and compel Japan to choose between their U.S. alliance partner or their neighbor China. Security imperatives will trump trade, and as a result, the Sino-Japanese relationship will recalibrate to face the new realities of great-power politics and a return of realpolitik.

Stephen Nagy is originally from Calgary, Canada. He is a senior associate professor at the International Christian University based in Tokyo. Concurrently, he is a distinguished fellow with Canada’s Asia Pacific Foundation and was appointed China expert with Canada’s China Research Partnership. He also holds fellowship positions with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute (CGAI) and the Japan Institute for International Affairs (JIIA). Concurrently, Stephen is a Senior Associate Professor in the Department of Politics and International Studies at the International Christian University, Tokyo. He was selected for the 2018 CSIS AILA Leadership Fellowship in Washington.

Image: Reuters