The United States Needs a Plan to Compete with Huawei

If the United States wishes to stop Huawei—and Beijing—from building our allies’ 5G infrastructure, it must consider a national project to do so.

It is likely that the recent Financial Times article by former GCHQ director Robert Hannigan caught U.S. alliance managers and intelligence officials completely by surprise. A seeming trial balloon by the UK government in advance of its ongoing telecommunications security review, the article argued that in assessing Chinese tech risks, the UK has a unique advantage because of its Huawei-funded facility at Banbury, which vets the Chinese company’s technology, code and practices. Following hard on the heels of the article, a second one cited a source inside the UK National Cyber Security Centre that said it would be possible to mitigate the risk from using Huawei equipment in the nation’s 5G networks. While it is true that the UK does have this center, it is also true that this center itself found that Huawei had not lived up to promises to improve its “engineering processes.” Its code has been sloppy, either out of laziness or ill intent. It is also true that—despite appearances and media reporting—the other Five Eyes share the United States’ concern.

Huawei messaging in London has been incredibly effective. For Britain’s foreign policy elites, debating and confronting Brexit on a daily basis, it is a frightening time, and Beijing has played its cards beautifully. “We still trust in the UK, and hope that the U.S. will trust us even more,” Huawei founder and CEO Ren Zhengfei told the BBC in a recent interview. He also promised to shift investment from the United States and put it in the UK. “We will invest even more in the UK. Because if the US doesn’t trust, us, then we will shift our investment from the U.S. to the UK on an even bigger scale.” Coming hard on the heels of a softening-up by Hu Chunhua, the vice-premier who canceled a trade-signing deal with Chancellor Philip Hammond over remarks made by Defence Minister Gavin Williamson, Britain seems close to capitulation. Even Alexander Younger, the MI6 chief who warned of Huawei’s insertion into UK infrastructure in December, seemed to change his tune, saying, it was more complicated than “in or out” when it came to managing the risks.

There is no doubt that this is one of the most critical moments in the history of both the Five Eyes intelligence grouping and in the Trans-Atlantic Alliance. U.S. alliance managers must take heed if they are to maintain the Special Relationship with Britain. There are a number of policy directions available to us, but they require considered action. The first of these is that the United States must provide its allies with an alternative. Simply rolling out the FBI, Homeland Security and Commerce in a slightly awkward press conference, providing slightly weak evidence will not cut it. The United States has come to an intersection: if it wishes to deny Huawei—and Beijing—the capability to build our allies’ 5G infrastructure, it must consider a national project to do so. Give London, Tokyo, Canberra and Ottowa a choice. For one, reconsider the memorandum written by Air Force Brig. Gen. Robert Spalding on a national effort to build 5G last year, while he was senior director for Strategic Planning. Yes, it’s true that was panned by the telecom industry, but frankly, they’re not in charge of our national security, nor are they cognizant of the wider geopolitical impact this will have on U.S. power and influence.

Second, Canberra and Washington will have to present a better case than they have done so already. The fact that UK experts are still able to say that there is no credible evidence of a risk reveals not only Huawei’s incredible PR talents, it also shows our failures to persuade. The case needs to be improved by the following means: (1) build up a dossier of case studies, including those in New Delhi, the Africa Union, Poland and Canada; (2) review at length the Australian Intelligence Service Organization report on a third country that was hacked by Huawei; and (3) track the money. Why is it that no study on Huawei’s incredibly low-cost products has been produced? It would almost certainly reveal the subsidies of the Chinese state—and hence its strategic direction—in supporting Huawei. If we are to persuade our allies in London that Huawei is an arm of the Chinese state, we must do so convincingly.

Third, the other four Eyes must be convinced by Britain that it is not merely bowing to economic considerations and allowing its carrier-led model to decide the issue. Britain will also have to fully explain and justify its risk assessment system, since it appears that the National Cyber Security Centre is prioritizing system failure over data leakage, and while system failure is obviously more of a critical issue for national security, British officials must explain where they’ve drawn the line in the trade-off between the two. It was disconcerting to be told in discussions with UK officials that data was always going to get out and one had to trade-off between the economic value of getting 5G infrastructure early and the loss of data. If Britain is going to say to the other four that it knows better, it will have to prove it, if it wishes to remain inside the intelligence alliance. While it sounds cruel to suggest a Britain being ousted from one of history’s longest-lasting alliances, the fact is that the consequences of Britain’s policy will have major repercussions on the other four, particularly, if the UK is wrong. It is important that we know, for example, whether Huawei involved in helping build China’s surveillance system in Xinjiang and China-proper. This is less an academic question and more an intention one, particularly when it comes to “smart city” programmes that Huawei is interested in trialing in the UK.

Historically, London has been caught out at its economical approach towards large-scale infrastructure funding and this has made it incredibly vulnerable to China, the one state that is willing to finance mega-projects like 5G. In addition to offering to finance and build Britain’s digital network, China is also willing to finance the country’s nuclear power plant expansion. From a grand strategic perspective, it looks as though Beijing has chosen to use London’s Brexit-based vulnerability to prise the UK away from the United States and its allies. This is not as impossible as it sounds, for it does not mean creating a Sino-British alliance, what it really means is nullifying Britain’s will to oppose its policy preferences. This only requires a “middleman” posture, a possibility I warned about in a piece for RUSI in 2016. In such a case, we will see a UK that is nominally inside NATO and the West, but one in which is increasingly intent on benefitting from a balancing posture between the United States and China. This would see a UK that pays lip service to the Western alliance, but that prioritizes mercantilism over its role as guarantor of the rules-based order. There are signs that Beijing is working hard for that eventuality and has put a number of attractive lures on the table to encourage this, including offering to make the City of London, the global trade hub for the RMB, creating the most Confucius Centers in Europe, investing in a massive new embassy complex near the financial center, and building an impressive new CGTN hub in West London. When one thinks about Britain’s global media reach, its financial markets, and its core technologies, it is clear that Huawei is not simply building a 5G network.

Dr. John Hemmings is Director of the Asia Studies Centre at the Henry Jackson Society and an adjunct fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies. He is based in London.

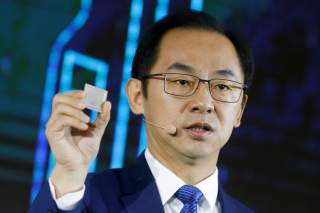

Image: Ryan Ding, the chief of Huawei's carrier business group, holds a Tiangang 5G base station chipset during a product presentation in Beijing, China, January 24, 2019. Reuters.