A War with North Korea Could Kill Millions—and Devastate the Global Economy

Any further escalation of the Korean Peninsula crisis could inflict economic pain across the globe.

North Korea has ignored international sanctions to test-fire eight ballistic missiles this year, as the “Hermit Kingdom” builds up its nuclear capabilities. Amid threats of nuclear war against the United States and its allies, the region is already suffering economic damage and even worse could lie ahead should the crisis escalate.

The latest ballistic-missile test on May 21 further ratcheted up tensions in the region, despite numerous warnings from the United States, Japan, South Korea and even North Korea’s major ally, China.

While the latest test flew an estimated 310 miles, North Korea’s previous test-firing of a Hwasong-12 flew at a step trajectory and was estimated capable of flying around 2,800 miles, within range of U.S. military facilities on Guam.

North Korea’s Foreign Ministry has stated that it will “react to a total war with an all-out war, a nuclear war with nuclear strikes of its own style . . . in the death-defying struggle against the U.S. imperialists.”

Even Australia has earned a mention, with Pyongyang warning that Australia’s comments in support of U.S. efforts to isolate the Stalinist state are “a suicidal act of coming within the range of the nuclear strike” from North Korea.

“The threat of a nuclear attack on Seoul, or Tokyo, is real, and it’s only a matter of time before North Korea develops the capability to strike the U.S. mainland,” U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson has warned.

In the firing line are some twenty-eight thousand U.S. military personnel in South Korea, forty thousand in Japan and the Guam base, while the United States is obliged to defend Japan under the postwar security alliance.

Financial Markets Calm

Yet despite Pyongyang’s hostile actions, financial markets have appeared relatively calm. Asian stock markets posted their fourth straight monthly rise in April, while the benchmark MSCI Asia-Pacific index has risen by 12 percent this year.

On May 25, South Korea’s benchmark Kospi Index hit a record high of 2,342, while Japan’s Nikkei Stock Average was at 19,813, up 3.6 percent for the year and only slightly below its year high. Even the Shanghai Stock Exchange’s composite index was showing a positive return for 2017, despite a crackdown by authorities on market speculation and Moody’s downgrade of Chinese debt.

The Japanese yen, typically a safe haven in times of crisis, has risen by 5 percent against the U.S. dollar this year, while the South Korean won has remained relatively stable.

“If you look at the reaction from the financial markets, the consensus is that nothing major will happen. We did see some impacts on U.S. bond yields when the U.S. aircraft carrier [USS Carl Vinson] was deployed, but it wasn’t very significant,” said Suman Neupane, senior lecturer in finance at Australia’s Griffith Business School.

Regional Economies Threatened

Yet the escalation of tensions on the Korean Peninsula has already caused economic damage, with potentially even worse ahead.

South Korea’s installation of the U.S. Terminal High Altitude Area Defense missile defense system in response to the crisis sparked economic sanctions from China, which sees the system as a threat to its national security.

According to Credit Suisse, China’s move to cancel tourist group tours to South Korea could cut 20 percent off South Korea’s GDP growth this year, given that Chinese tourists inject $7.3 billion a year into the Korean economy.

South Korean consumer stocks were also hit, after China also moved to restrict sales of Korean cosmetics and entertainment along with duty-free shops and Korean casinos. Consumer-goods company Lotte Group was singled out, since it has provided land to host the missile defense system in Korea.

“We don’t have to make the country bleed, but we’d better make it hurt,” China’s Global Times newspaper warned Seoul.

China itself could also suffer though, given reports that U.S. sanctions against North Korea could include penalties against Chinese banks and companies doing business with the regime.

North Korea is economically dependent on China, with which it conducts almost 90 percent of its trade, including exports of coal, iron ore and zinc, along with seafood and textiles.

Despite reported Chinese sanctions on the North, the latest data actually showed a 37 percent increase in Chinese trade during the first quarter of 2017. Chinese exports to North Korea increased by nearly 55 percent, while Korean imports rose by 18 percent, China’s customs administration said.

Japan, Asia’s second-largest economy, also faces the risk of a strengthening currency, given the yen’s safe haven status during times of crisis. An appreciating yen would hit exporters’ profits along with Tokyo stocks, harming the Abe administration’s “Abenomics” program aimed at reviving growth.

“Japan’s economy would be impacted directly, whether or not a conflict occurs, if air and sea routes in the areas between China and Japan were blockaded,” said Nikko Asset Management’s chief strategist, Naoki Kamiyama in a May research note. “If Japanese firms manufacturing electronics in China using Japan-made machinery and parts had to suspend production for several months, profits would be negatively impacted. Also, an attack on U.S. troops stationed in Japan would affect production levels there.”

“The issue is how long any disruption would last, as the extent of the impact on the economy would depend on the duration.”

Kamiyama expects the Japanese yen to appreciate if Japan is not directly entangled in a conflict, while direct involvement would hit the yen along with Japanese bonds and stocks. Other likely impacts would be a rise in oil and other commodity prices and reduced global economic growth, while increased military expenditure by Washington could crimp activity.

“If the crisis plays out longer, there may be a significant increase in demand for safe haven assets such as the Japanese yen, U.S. Treasuries and gold,” Griffith’s Neupane said.

The Korean won, bonds and stocks would similarly face selling pressure should the crisis worsen further.

Should Trump order a preemptive strike on North Korea, both South Korea and Japan would face the risk of a counterattack, potentially devastating Seoul and putting Japanese cities under threat of missile attack.

And should the North collapse, the cost to Seoul of reunification has been estimated at $3 trillion, according to Australian National University researcher Leonid Petrov.

Petrov estimates it would take “at least a decade” for full reunification, saying the reunification of East and West Germany was a “walk in the park” compared to the Koreas.

Ultimately, North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un’s saber rattling is likely aimed at securing economic concessions in return for a suspension of further missile tests. But given the importance of Asia to world economic growth, any further escalation of the crisis could inflict economic pain across the globe.

Anthony Fensom, a Brisbane, Australia-based freelance writer and consultant with more than a decade of experience in Asia-Pacific financial/media industries. You can find him on Twitter: @a_d_fensom.

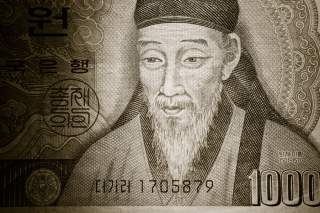

Image: South Korean thousand-won bill. Wikimedia Commons/Creative Commons/Brandon Oh