Why Washington Can't Quit Qatar

America’s mixed messages on the Qatar crisis have illustrated the complex nature of the allegations against the gas-rich Arabian emirate.

Journalists in Middle Eastern media outlets have been engaged in harsh mudslinging ever since Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Egypt, and Bahrain (aka the quartet) severed diplomatic and economic relations with Qatar in June over Doha’s alleged support for the Islamic State (ISIS), al Qaeda, and Iranian-backed militias in numerous Arab states. Although some maintain that the move was long overdue, others argue that for Saudi Arabia to lead the charge was akin to the pot calling the kettle black and that Riyadh, more than any Arab capital, has promoted violent extremism across the Muslim world.

Based on the words and actions of the American diplomatic establishment and the Pentagon since the Qatar crisis erupted, it is clear that Washington plans to continue working closely with all Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states in the struggle against terrorism. Nonetheless, the U.S. government’s mixed messages on the Qatar crisis have illustrated the multifaceted and complex nature of the common allegations against the gas-rich Arabian emirate.

High-ranking officials on both sides of the partisan divide in Washington have pointed their fingers at Doha and/or Riyadh, viewing both of them as part of the problem. During Barack Obama’s presidency, Qatar’s ties with Hamas and other Sunni Islamist factions elicited strong condemnation from U.S. lawmakers such as then-Sen. John Kerry (D-MA), who in 2009 said that “Qatar can’t continue to be an American ally on Monday that sends money to Hamas on Tuesday.”

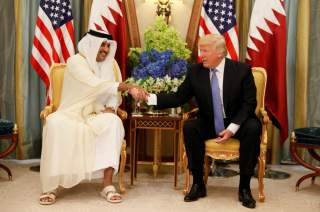

In June, U.S. President Donald J. Trump accused “high level” officials in Doha of supporting terrorism, as have neoconservative think tanks, congressmen and former Defense Secretary Robert Gates.

Earlier in July, in response to the quartet’s thirteen demands for reconciliation with Doha, U.S. Secretary of State Rex Tillerson’s communications adviser, RC Hammond, asserted that “this is a two-way street” and that “there are no clean hands.” On July 12, U.S. Sen. Bob Corker (R-TN), who chairs the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, stated that “the amount of support for terrorism by Saudi Arabia dwarfs what Qatar is doing.” Last year, U.S. lawmakers overrode Obama’s veto and passed the Justice Against Sponsors of Terrorism Act (JASTA), which implied that the Saudi government had a hand in the 9/11 terrorist attacks. As a candidate for president, Trump supported the legislation, as did Hillary Clinton, his Democratic opponent in the presidential election, although JASTA’s future now appears uncertain.

In the immediate aftermath of Tillerson’s shuttle diplomacy in the GCC, in which he said that Doha’s response to the quartet’s demands were “very reasonable,” it is clear that Washington’s diplomatic establishment continues to value Qatar as a close American ally. Moreover, the United States and Qatar signed a counterterrorism agreement when Tillerson was in Doha on July 11, which followed the two countries completing a $12 billion fighter jet deal in June. The following day, Trump stated in an interview with CBN News: “We are going to have a good relationship with Qatar and not going to have a problem with the military base [at al-Udeid].” Evidently, despite Trump’s tweets, Washington and Doha are set on maintaining close ties with the former rejecting the quartet’s case for blockading the latter.

Will this antiterror agreement shift the focus toward Riyadh and other GCC capitals which have accused Doha of patronizing extremism? It appears so. Now the Qataris can claim that they are complying with Washington’s standards for countering terrorism. Either the Saudi/UAE-led bloc of states will now come under pressure to sign similar agreements or explain the reasons behind their refusal to do so. In any event, Washington and Doha’s signing of this agreement will undermine the quartet’s efforts to convince the United States to see Qatar through their lens.

For all of the White House’s communications challenges, the U.S. government is committed to strengthening Washington’s counterterrorism cooperation with both Saudi Arabia and Qatar, and intends to nudge Riyadh and Doha toward reconciliation. Tillerson’s aim is to strengthen the United States and its Sunni Arab allies’ position vis-à-vis ISIS and other militant Salafist-Jihadist forces, as well as an ascendant Iran. Should diplomatic efforts to mediate a resolution to the Qatar crisis that leaves both sides with a sense security and dignity prove futile, the Trump administration will face a more challenging environment in the Middle East. This will limit the extent to which the White House can achieve its objectives in the region.

Giorgio Cafiero is the CEO of Gulf State Analytics (@GulfStateAnalyt), a Washington, DC-based geopolitical risk consultancy. Daniel Wagner (@Countryriskmgmt) is managing director of risk solutions at Risk Cooperative.

This article also appeared on the Atlantic Council's New Atlanticist blog here.