Why Xi is Purging the Chinese Military

Much has been made of the flurry of announcements in recent months by Xi Jinping—China’s president, general secretary of the Chinese Communist Party, and chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC)—signaling major structural reforms to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), scheduled for completion by 2020. Veteran China watchers have diligently catalogued what is known and unknown at this point from authoritative pronouncements, and what is speculated on the basis of unofficial sources. Observers, for example, have paid especially close attention to Xi’s establishment of the PLA Strategic Support Force and ruminated over its stature in the PLA vis-à-vis the services, as well as its precise role and mission. Analysts have also pondered questions such as the future membership of the CMC and how cooperative the traditionally army-dominated top levels of the PLA’s leadership will become under the reforms.

While understanding the details of Xi’s reforms is critical to assessing the direction of PLA modernization going forward, it is also necessary to consider the broader implications of Xi’s apparent relationship with the military. Many observers have stated the obvious: Xi is as “large and in charge” in military circles as he is in Chinese politics generally. This is true, but his control over the PLA deserves more attention than it has received. That is the subject of this article. We argue that Xi is reviving Maoist-style tactics—including purges of corrupt officers, forced public displays of respect for Mao and support of Maoist thinking, and a formidable internal monitoring system—to ensure his personal dominance over the military. Xi’s leadership style vis-à-vis the military will have profound implications for civilian-military relations in China.

Purging the Military

When Xi assumed power in November 2012, he vowed to fight both “tigers” and “flies”—a reference to taking on corrupt leaders as well as lower-level bureaucrats engaged in corrupt practices throughout the Chinese system. The PLA would be no exception.

The first warning shot was aimed toward the tigers. In 2014, Xi arrested a former CMC vice chairman, Xu Caihou, for participating in a “cash for ranks” scheme. After expelling Xu from the party, Xi followed up in 2015 with the arrest and purging of another former CMC vice chairman, Guo Boxiong, on similar charges. The arrests were unprecedented in that Xu and Guo were the two highest-ranking officers in China’s military when they served as CMC vice chairmen, and their arrests marked the first time the PLA’s highest-level retired officers faced corruption charges. As of early March 2016, Xi’s anticorruption campaign had resulted in the arrest of at least forty-four senior military officers, although the actual numbers could be higher.

Xi did not forget about the flies, either. At least sixteen lower-level military officers are facing punishment for corruption charges as well. The military anticorruption drive is part of a much broader dragnet: all told, nearly 1,600 individuals throughout China’s government are either under investigation for corruption, or have been arrested, purged or sentenced since Xi came to power.

The only other PRC leader that resorted to purges at such a high level—and so routinely—was Mao. After the establishment of the PRC in 1949, there were at least four major purges; two of these episodes involved military leaders. Mao first purged his defense minister Peng Dehuai in 1959 for questioning the disastrous Great Leap Forward. Peng’s purge was more about leadership politics than it was a struggle between Mao and the PLA, but Peng was also known as an advocate of Soviet-style military modernization and professionalization, which Mao believed ran contrary to his own emphasis on political indoctrination. Mao’s second purge of the PLA occurred in 1971, against the lieutenants of Peng’s replacement Lin Biao, who was widely viewed as Mao’s heir apparent during the tumultuous years of Mao’s Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution. Although historical accounts differ on the details, it appears that Mao suspected Lin was involved in plotting a coup against him, perhaps impatient to replace the “Great Helmsman” as China’s supreme leader. Whatever Lin’s knowledge or involvement, he suffered the consequences when he died in a plane crash as he was supposedly fleeing China en route to the Soviet Union. A substantial number of Lin’s supporters were reportedly purged following his mysterious death.

According to one recent assessment, Xi’s anticorruption campaign represents the largest systematic purge since Lin’s death and, according to new analysis from noted China scholar David Shambaugh, the largest in PRC history. Xi’s immediate predecessors, Hu Jintao and Jiang Zemin, both used such purges sparingly. More to the point, neither Hu nor Jiang ever used them against the PLA in so daring a manner, probably because neither had the stature among top brass to do so. Even Deng Xiaoping, who like Mao was a paramount leader himself, never technically purged the PLA in the way Xi has done. It is often said that Deng “purged” fellow communist revolutionaries General Yang Shangkun and General Yang Baibing (the “Yang brothers”) after suspicions that they were trying to depose Jiang Zemin, who was then Communist Party general secretary. Deng forced Yang Shangkun to retire, and sidelined Yang Baibing by removing him from the CMC, in effect ending their influence over the PLA. But it is important to note that neither was arrested or expelled (i.e. purged) from the party. In fact, in the case of Yang Shangkun, he retained ceremonial honors until his death.

In contrast to Jiang’s approach, Xi’s anticorruption campaign has regularly featured expulsion from the party and harsh punishment. To be sure, Xi seems focused on cleaning up rampant corruption when deciding whether to purge military officers, whereas mere disagreement with Mao was often sufficient for removal—and in some cases far worse, with punishment so severe that it resulted in the demise of some of Mao’s ousted rivals. It would also appear that purges might not be the first go-to option, as Xi has relied on massive reshufflings of military officials to reduce their influence, echoing tactics that Deng Xiaoping employed as China’s top leader.

Returning Mao to the Forefront of Thought

Since Mao’s death in 1976, his successors have tended to emphasize pragmatic and scientific thinking over conducting daily business in the spirit of Maoist thought. Xi, however, believes that a lack of civilian leadership intervention, especially under Hu and Jiang, has resulted in a substantial drift of the PLA away from party oversight. This, in Xi’s view, explains why the PLA has become so pervasively corrupt. Xi therefore instills fear in his senior military officers by reminding them that his “core” leadership status allows him to intervene at will to curb the PLA’s excesses. Regardless of whether Xi finds any truth in Maoist thought, he appears to see some utility in exploiting a supposed lack of adherence to it as a way to cow the military.

Xi drew a direct line between Mao and the present at a major meeting in November 2014. In commemoration of the eighty-fifth anniversary of the so-called Gutian Congress, at which Mao first affirmed the party’s absolute control over the military in 1929, Xi convened 420 of his most senior officers to meet in the small town of Gutian in southeastern Fujian Province. To our knowledge, this was the first time a PRC leader reconvened military leadership at Gutian since Mao—symbolism that was certainly not lost on the top brass.

The atmospherics of the 2014 Gutian meeting was perhaps best captured by Dr. James Mulvenon, vice president for intelligence at Defense Group, Inc., who describes scenes of military officials who “gazed upon a statue of Mao Zedong ‘with reverence,’ dined on a likely Spartan representation of something called the ‘Red Army meal,’ studied historical documents, listened to lectures about ‘tradition,’ and saw ‘red movies.’” Mulvenon goes on to detail a scene in which “Xi climbed the 151-flight staircase of the Chairman Mao Memorial Garden, ‘respectfully laid a floral basket at Mao Zedong statue, personally smoothed out the ribbons on the floral basket, led the people to bow three times to Mao Zedong statue, paid homage to the statue, and deeply remembered the great exploits of the revolutionaries of the older generation.’”

Besides the obvious deference to Mao, Gutian’s message was also very much derived from Mao’s notion of the proper balance between the party and military. Prior reading material, for example, reaffirmed the unassailable and preeminent position the party has over the military. This set the stage for Xi to implicitly convey to all in attendance that they, too, could become victims of his anticorruption campaign, just as General Xu had a few months earlier, if they refused to “deeply reflect on the lessons learned and thoroughly exterminate its influence.” According to Mulvenon, Xu’s successful purge probably contained enough incriminating material to be used against everyone present at Gutian, which may be the most important source of Xi’s power over the PLA.

Establishment of the CMC Chairman Responsibility System

Finally, Xi replaced the “CMC Vice Chairman Responsibility System” with a new “CMC Chairman Responsibility System.” From Xi’s perspective, the CMC Vice Chairman Responsibility System featured Hu and Jiang as figureheads while the PLA itself handled most decisions, particularly important administrative and personnel issues, which were the genesis of precisely the types of corruption scandals that involved former CMC vice chairmen Xu and Guo. Formally announced as part of Xi’s structural military reforms in January, the new system grants Xi full authority to manage the PLA and to intervene personally when deemed necessary. According to one source, Xi spends a half a day per week on average in his CMC office addressing military affairs—a stark contrast to Hu Jintao, who rarely worked there.

Xi’s new, self-appointed direct involvement moves him one step closer to acquiring Mao’s unfettered access to and influence over the PLA. Because the CMC Chairman Responsibility System and the PLA’s organizational reforms abolished the PLA’s four general departments, this means that the CMC now has direct control over the PLA’s top commanders, making resistance to Xi’s directives, or perhaps even feigned compliance, more of a challenge. In addition, the system will include a new disciplinary committee charged with monitoring and punishing corrupt PLA officials.

Implications

Xi’s tactics for handling the PLA, which echo Mao in certain respects, could have several significant consequences. First, Xi’s approach is not without its risks. The intense pressure wrought from Xi’s anticorruption campaign could foment rising dissatisfaction with and opposition to Xi’s leadership. Last month, for example, disaffected Communist Party members reportedly penned an open letter to Xi calling for his resignation. It was published briefly online and then removed by authorities. Hostility toward Xi’s style of rule seems real, and some observers have speculated that in an extreme but highly unlikely event, Xi might even become the victim of a coup attempt. After all, it was Mao’s defense minister Lin Biao who allegedly considered removing Mao because of the dire conditions created by the ideological witch hunt of the day—the Cultural Revolution. It would be extremely difficult, however, to muster enough credible opposition to Xi given his robust monitoring of corruption and disloyalty in the PLA ranks. Even if a coup is far-fetched, however, tensions could rise between the PLA and Xi in the coming years if officers perceive that his approach to the military is aggressive and high-handed.

It will also be instructive to see how Xi’s reassertion of paramount leader-type power over the PLA plays out for his successor. The general trend after Deng had been to increasingly leave the PLA to its own devices. Jiang ordered the PLA to get out of business and focus on improving its professionalism and combat capabilities, but by the time the torch had passed to Hu, he had very little leverage over the military and had to find ways to work with senior military officials that were mutually beneficial in nature. Like Jiang, Hu lacked any military experience and did not have anything approaching the stature of Mao and Deng, who were vaunted communist revolutionaries. This made his time as China’s commander-in-chief exceptionally challenging.

The trend has certainly reversed under Xi, but will more personalized control over the PLA continue after him? The critical factor in answering this question may be whether Xi’s successor is the scion of a well-respected communist revolutionary or otherwise possesses ties to the PLA. Xi is the son of a former revolutionary and served briefly in a secretarial position for a top CMC official. It is difficult to imagine that a future leader would have such personal control over the military without connections to it or the PRC’s revolutionary past.

Another important question that we can probably put to rest, at least for now, is whether the PLA is a rogue actor in the Chinese system. Clearly, the military is more closely managed under Xi than at any time since Mao. And now that the general departments have been reconstituted and placed directly under the CMC, commanders may have to respond directly to a new joint staff or even the CMC itself. On its face, this new chain of command might be a hindrance to decisionmaking downrange, whether pertaining to the South China Sea, Taiwan or elsewhere. To be sure, Xi’s new war zone commands—announced as part of the sweeping military reforms—are supposed to empower, not limit, commanders to make critical decisions. We will have to wait and see how this dynamic progresses.

Finally, despite some speculation to the contrary, Xi’s assertion of control over the military is unlikely to negatively impact the PLA’s ongoing modernization efforts. Part of Xi’s “China Dream” is to produce a strong military capable of deterring, or if necessary taking on powerful potential adversaries including even the United States. Xi seems intent on keeping his anticorruption campaign and homage to Mao severely circumscribed, to focus on combating the problem of corruption and rooting out any disloyalty or opposition to reform within the ranks. Mao, on the other hand, sought ideological purity as defined by him at the expense of PLA modernization and professionalization efforts.

To date, there is no evidence that Xi is considering this path. In fact, his military reforms suggest quite the opposite: Xi wants a PLA that demonstrates utmost loyalty to the party, but he also wants a far more competent and operationally capable PLA by 2020—one that is commensurate with China’s status as a major world power and capable of protecting China’s regional and global interests.

Derek Grossman is a senior project associate at the nonprofit, nonpartisan RAND Corporation. Michael Chase is a senior political scientist at RAND and a professor at the Pardee RAND Graduate School.

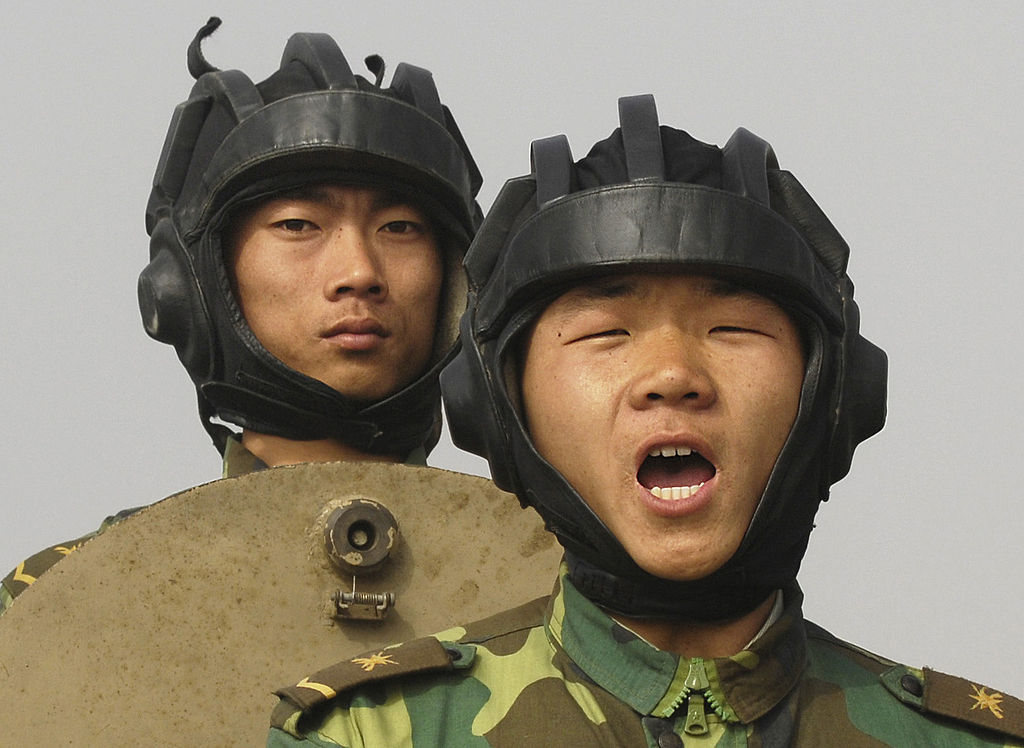

Image: Flickr/Johnathan Nightingale