Will Erdogan’s Turkey Gain From the War in Ukraine?

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has opened up new opportunities for Turkey, but Erdogan should not overplay his hand.

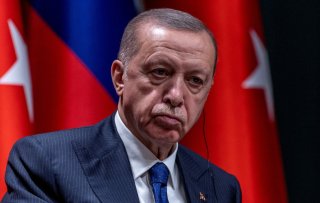

Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdogan turns crises into opportunities—it’s his modus operandi. The crisis around Ukraine is only the latest example. After the initial shock of the Russian invasion, which put Turkey in an uncomfortable position, Erdogan now seems to be enjoying the new geopolitical reality. The West and Russia are where he wants them to be: the former beholden to him, the latter too weak to go against him. Or so he thinks.

In the aftermath of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Turkey’s key role in Black Sea security and Erdogan’s gymnastic balancing act between Moscow and Kyiv substantially boosted Ankara’s standing in the West. After years of frosty relations over a host of issues, including Turkey’s incursion into northern Syria and purchase of the Russian S-400 missile defense system, which prompted Western sanctions, relations between Turkey and its Western allies are cordial again. Turkey’s drone sales to Ukraine and its decision to close the Bosporus and Dardanelles to Russian warships, exercising Ankara’s right under Article 19 of the 1936 Montreux Convention, and its airspace to Syria-bound Russian aircraft have won Turkey praise in Western capitals. Boosting Turkey’s standing further is Ankara’s recent offer to help clear mines off the coast of the Ukrainian port of Odesa and escort ships carrying Ukrainian agricultural products to avoid a major global food crisis. Erdogan is confident that the West has finally understood Turkey’s indispensable role in Western security. Swelling his confidence is the veto card Turkey holds against Sweden and Finland’s bid to join NATO, a move that will transform Europe’s security landscape.

The greater strategic importance that Turkey has assumed for Western efforts to counter Russia in the wake of its invasion of Ukraine provides Erdogan with the perfect opportunity to extract concessions from the West. One key area for Erdogan in this regard is defense procurement. Several EU countries, including Sweden and Finland, halted arms exports to Turkey over the country's late 2019 military incursion into northern Syria. However, the genuinely disruptive setback came earlier in 2019 with the U.S. decision to block the sale of F-35 warplanes to Turkey after Ankara bought the Russian-made S-400 missile defense system. Turkey has since requested to purchase forty new F-16 fighter jets and eighty modernization kits for its existing fleet. However, members of Congress have been piling pressure on the Biden administration to prevent the sale. Western sanctions have upset Turkey’s modernization plans and dealt a significant blow to its defense industry.

One key area where sanctions have created a bottleneck is engine technology. Turkey is unable to produce its own engines, hindering the country’s otherwise burgeoning defense sector. Before the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Turkey entertained several options to overcome these challenges. One idea was to purchase Russian fighter jets. Another was cooperating with Ukraine, which has successfully sustained its Soviet-era legacy of designing and manufacturing engines capable of powering many different types of aircraft. However, the Ukraine crisis made those plans unfeasible, at least for now. Russia's dismal military performance in Ukraine and the stigma associated with Russian brands have all but eliminated the option of buying fighter jets from Moscow. The war’s uncertainty has also upended Turkey’s plans to cooperate with Ukraine to address its defense needs, forcing Ankara to turn back to Western markets. Erdogan hopes to use Turkey’s renewed status as a key NATO member and its veto power over Sweden and Finland’s accession to force Western countries to lift restrictions on defense exports to Turkey.

Erdogan wants to take advantage of a weakened Russia as well. He has long sought to launch another military operation into northern Syria to establish a safe zone that can host some of the 3.6 million Syrian refugees living in Turkey. However, Russian and U.S. objections put his plans on the back burner. Erdogan seems to be calculating that this is the perfect time to launch a fresh incursion, given Russia’s distraction in Ukraine and the growing nationalist backlash against Syrian refugees at home ahead of the 2023 elections. He wants to utilize Turkey’s veto power over Sweden and Finland’s NATO membership to ensure Western acquiescence.

Erdogan might get some of the things he wants if Sweden and Finland lift their restrictions on exports of defense equipment to Turkey or Russia greenlights another Turkish incursion into northern Syria. But Erdogan’s efforts to strong-arm Washington could also backfire as another Turkish operation into Syria is likely to strengthen the anti-Erdogan front in Western capitals.

The Biden administration seems willing to sell Turkey the F-16s. In a letter to Congress, the State Department said a potential sale of F-16 fighter jets to Turkey would be in line with U.S. national security interests and would also serve NATO's long-term unity. Erdogan’s stance over Ukraine had convinced some critical members of Congress to back the sale, but Erdogan’s recent threat to block Sweden and Finland’s accession to NATO seems to have changed the mood on the Hill, with a bipartisan majority raising concerns about what they see as Erdogan’s blackmail. The rising tension between Greece and Turkey is not helping Erdogan either.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has opened up new opportunities for Turkey, but Erdogan should not overplay his hand. Turkey’s opportunistic posturing and obstruction of Sweden and Finland’s NATO bid could become another milestone in its diminishing standing as a NATO ally.

Gonul Tol is the Director of Turkish Program at the Middle East Institute.

Alper Coskun is a Senior fellow within the Europe Program at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Image: Reuters.