Is the World Big Enough for Middle Powers?

Hope for stepping back from the precipice best rests on bringing difficult questions of values and political culture—and their compatibility with the liberal order—back to the table.

These issues provide the broader context underlying concerns over China’s alleged attempts to reshape the UN and other global bodies. China’s influence in the UN arguably peaked in 2020, when its citizens held leadership posts in four of the fifteen UN specialized agencies, as well as the position of under-secretary-general for the UN Department of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA). While Beijing’s new-found influence cast a shadow over the World Health Organization during the Covid-19 pandemic and helped bring DESA on board to assimilate China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) into the UN Sustainable Development Goals, a bigger concern has been its attempts to restrict the participation of human rights NGOs in events and impede the UNCHR from fulfilling its mandate. In June of the following year, UNCHR high commissioner Michelle Bachelet was left to lament “the most wide-reaching and severe cascade of human rights setbacks in our lifetimes,” criticizing, among other problems, the “chilling impact” of the introduction of Hong Kong’s national security law. She waited till just before midnight on August 31, merely minutes before the expiration of her four-year term, to release her long-awaited report on alleged human rights abuses in Xinjiang.

Middle Democracies: Between a Rock and a Hard Place

This backdrop brings us back to where we are today. Biden has reasserted America’s commitment to the UN and the “rules-based order,” winding back the “America first” rhetoric of his predecessor, former President Donald Trump. But if anything, he has gone far further than Trump in leveraging values-based alliances, as well as American military, economic and structural power, to create parallel institutions that not only hedge against the subversion of these global bodies but also undermine their primacy as instruments for managing disputes between world powers. It is patently clear that the core guiding tenet of these new institutions is containing America’s primary geostrategic rivals, China and Russia.

For instance, in response to Russia’s stumbling invasion of Ukraine, U.S.-led countermeasures largely bypassed the UN, and military assistance aside, brought to bear the full weight of Western (and Western-allied) systemic power in areas such as trade, finance, and technology supply chains. Some of that disruptive power is now being directed towards China, especially in relation to access to cutting-edge technology. On the American side, the demonstrated potency of these measures in the wake of the Russian invasion is arguably proving to be a drawcard to democratic allies, which may in turn have been a factor inspiring NATO to shift its attention to China and the Pacific, in alignment with the increasingly popular “one theater” (or combined theater) thesis. These precedents also threaten to further weaken the liberal international order by drawing other less democratic or authoritarian governments, fearful of being targets of similar measures, into a resilience strategy that brings them closer into Beijing’s orbit, potentially strengthening the latter’s own counter-ballasts against Western systemic power.

It should be noted that this multifaceted mobilization of alliances arguably extends in scope beyond anything the United States did in the latter part of the Cold War. During that period, U.S. analysts also decried the strategic subversion of the UN by the Soviet Union, which similarly had some success in rallying the Global South. Yet the efforts of the Soviet Union to accumulate structural power through global bodies were hampered by its relative economic weakness. With China’s near-peer status vis-à-vis the United States extending to economic and technical strength, and its prospects of greater success in translating this into structural power, old alliances, as well as new ones such as the Quad, are branching out from platforms narrowly preoccupied with defense and security cooperation, extending to the dimensions of economics, infrastructure, trade, regulation, supply chain security, and technology cooperation. While pledging to sustain the “rules-based order,” they are essentially reconstructing it.

In the Pacific, the domain of China’s more immediate push for regional hegemony, this situation is shrinking the middle ground for liberal democratic middle powers that have long enjoyed close security relations with Washington yet have retained strong economic ties with China. And there are inchoative signs that they are leaning towards entering a U.S.-led security and economic bloc. Australia, having for some years been the most vocal middle power critic of China’s hegemonic ambitions and a victim of punitive trade measures from China, has enthusiastically signed up to this broader-spectrum Quad and other programs aimed at re-engaging Washington in what it openly acknowledges to be a strategic competition for regional influence. Australia has also attempted to diversify its trade and increase security over critical knowledge, infrastructure, and innovation drivers. And, echoing the tenets of a 2021 government report, Australia is facing calls to enhance its technological sovereignty by developing an indigenous semiconductor manufacturing capacity, which Australia-China Relations Institute researcher Marina Zhang cautions could mean a step towards “technology decoupling.”

But this is also happening in democratic regional powers that have traditionally managed their relationship with China with far more success. The election of Japanese prime minister Fumio Kishida, known previously for a “dovish” foreign policy outlook, was expected to help Japan improve its relationship with China. Instead, Kishida has enthusiastically touted the Quad, tightened security cooperation with Washington and Australia, supported the Chip 4 Alliance (aimed at blocking China from semiconductor/high-performance chip supply chains), and passed an economic security law described by the Nomura Research Institute as “mainly devised to counter China.” Kishida later gave the post of minister of state for economic security to Sanae Takaichi, a strong critic of Chinese intellectual property theft who holds hawkish views on defense and diplomacy and sees overreliance on Chinese trade as a “grave” risk to Japan’s economic security. More recently, Japan’s ambassador to Australia, Yamagami Shingo, advocated that Australia block China from joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), arguing that “economic coercion has become a signature modus operandi” of Beijing’s foreign policy.

Finally, even South Korea—long one of the U.S. allies most friendly towards China—has seen its new conservative president, Yoon Suk-yeol, promise to “work together with like-minded nations that respect freedom,” a vow that has been described as a pledge to build “a value-based alliance with Washington.” Despite South Korea being tethered to China geographically and economically and Seol’s view of Beijing as an essential player in curtailing North Korean aggression, Yoon has agreed to preliminary negotiations on the Chip 4 Alliance and reinvigorated trilateral defense cooperation with Washington and Tokyo.

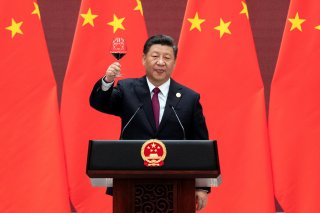

It increasingly seems that there is no easy path to safer pastures amid diminishing prospects for a middle way that combines a strong trade relationship with China and a strong American security license. Xi’s Putinesque rise towards lifelong, centralized leadership, his growing emphasis on power projection and national security, a litany of alleged Chinese human rights abuses, and other factors, such as China’s “economic coercion,” are making acquiescence to China’s regional ascendency a less tolerable proposition. And it is increasingly apparent that these middle countries must play an active role for there to be any hope of shoring up America’s waning regional hegemony.

As the scope of this alliance expands to account for the ongoing economic, technical, and diplomatic dimensions of China’s rise, and in doing so reduces the functionality of broader multilateral platforms, these nations will face a challenging paradox: forming a strategic bloc for the defense of their values might come at a cost to their agency. It will no doubt also eventually come at the expense of some of their interests. The reality is that locking themselves into the American-led alliance will not only expose these middle powers to grave consequences should America’s containment strategies fail but will also open them to unilaterally determined forms of obligation creep. Harsh American measures, such as recent restrictions that could mean China-based tech workers will have to choose between their jobs and their American citizenship, could well come with demands for mirror or aligned regulations among partner nations with whom America’s technology and security interests are integrated. Certain lucrative commodities with geostrategic importance, such as Australia’s burgeoning lithium trade with China, could well be subject to economically costly controls.

Finally, this direction will also mean that security is predicated upon nations’ success in making ongoing and inevitably costly investments in retaining the balance of power. Investing in reducing the primacy of the international bodies in which middle powers engage multilaterally with China, in addition to pursuing resilience strategies that reduce trade independence with Beijing, will remove the role of key buffers that mitigate the risks of diplomatic spats escalating into tensions or outright conflict. Actively blocking China’s structural, economic, and systemic avenues to assuming global hegemony, which Beijing sees as legitimate domains of great power competition and preferable to war, could increase China’s appetite for military conflict at the very time that a looming demographic crisis hastens Beijing’s strategic tempo.

Crises and Opportunities?

All this underlies that in this race to keep the world from a point of no return, a rapid change in tack is needed. The role of liberalized global markets in bringing unprecedented prosperity—and the need for nations to work together to address global crises such as climate change—continues to offer compelling arguments for the retention of the liberal international order. But it is evident that this is no longer enough to convince many states—and, most importantly, the world’s largest superpowers—to put aside their differences. There can be no coming together when pressing points of contention are in fundamental ways politically existential, especially when contentions are magnified by high levels of global integration or the effect of global free trade in amplifying and unevenly distributing systemic power.