A Professor Asks a Serious Question: Can Anthrax Cure Cancer?

Let's test it on dogs first to make sure.

Can the feared anthrax toxin become an ally in the war against cancer? Successful treatment of pet dogs suffering bladder cancer with an anthrax-related treatment suggest so.

Anthrax is a disease caused by a bacterium, known as Bacillus anthracis, which releases a toxin that causes the skin to break down and forms ulcers, and triggers pneumonia and muscle and chest pain. To add to its sinister resumé, and underscore its lethal effects, this toxin has been infamously used as a bioweapon.

However, my colleagues and I found a way to tame this killer and put it to good use against another menace: bladder cancer.

I am a biochemist and cell biologist who has been working on research and development of novel therapeutic approaches against cancer and genetic diseases for more than 20 years. Our lab has investigated, designed and adapted agents to fight disease; this is our latest exciting story.

Pressing needs

Among all cancers, the one affecting the bladder is the sixth most common and in 2019 caused more than 17,000 deaths in the U.S. Of all patients that receive surgery to remove this cancer, about 70% will return to the physician’s office with more tumors. This is psychologically devastating for the patient and makes the cancer of the bladder one of the most expensive to treat.

To make things worse, currently there is a worldwide shortage of Bacillus Calmette-Guerin, a bacterium used to make the preferred immunotherapy for decreasing bladder cancer recurrence after surgery. This situation has left doctors struggling to meet the needs of their patients. Therefore, there is a clear need for more effective strategies to treat bladder cancer.

Anthrax comes to the rescue

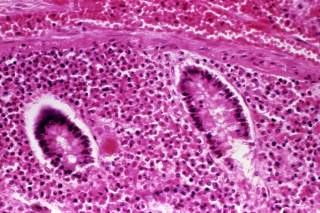

Years ago scientists in the Collier lab modified the anthrax toxin by physically linking it to a naturally occurring protein called the epidermal growth factor (EGF) that binds to the EGF receptor, which is abundant on the surface of bladder cancer cells. When the EGF protein binds to the receptor – like a key fits a lock – it causes the cell to engulf the EGF-anthrax toxin, which then induces the cancer cell to commit suicide (a process called apoptosis), while leaving healthy cells alone.

In collaboration with colleagues at Indiana University medical school, Harvard University and MIT, we designed a strategy to eliminate tumors using this modified toxin. Together we demonstrated that this novel approach allowed us to eliminate tumor cells taken from human, dog and mouse bladder cancer.

This highlights the potential of this agent to provide an efficient and fast alternative to the current treatments (which can take between two and three hours to administer over a period of months). I also think it is good news is that the modified anthrax toxin spared normal cells. This suggests that this treatment could have fewer side effects.

Helping our best friends

These encouraging results led my lab to join forces with Dr. Knapp’s group at the Purdue veterinary hospital to treat pet dogs suffering from bladder cancer.

Canine patients for whom all available conventional anti-cancer therapeutics were unsuccessful were considered eligible for these tests. Only after standard tests proved the agent to be safe in laboratory animals, and with the consent of their owners, six eligible dogs with terminal bladder cancer were treated with the anthrax toxin-derived agent.

Two to five doses of this medicine, delivered directly inside the bladder via a catheter, was enough to shrink the tumor by an average of 30%. We consider these results impressive given the initial large size of the tumor and its resistance to other treatments.

There is hope for all

Our collaborators at Indiana University Hospital surgically removed bladder cells from human patients and sent them to my lab for testing the agent. At Purdue my team found these cells to be very sensitive to the anthrax toxin-derived agent as well. These results suggest that this novel anti-bladder cancer strategy could be effective in human patients.

The treatment strategy that we have devised is still experimental. Therefore, it is not available for treatment of human patients yet. Nevertheless, my team is actively seeking the needed economic support and required approvals to move this therapeutic approach into human clinical trials. Plans to develop a new, even better generation of agents and to expand their application to the fight against other cancers are ongoing.

R. Claudio Aguilar, Associate Professor of Biological Sciences, Purdue University. This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Media: Reuters