The Scorpion on the Potomac: Navigating Drew Pearson’s Washington

Donald A. Ritchie’s The Columnist: Leaks, Lies, and Libel in Drew Pearson’s Washington offers a probing look at one of the most controversial journalists to ever stalk the halls of power.

Donald A. Ritchie, The Columnist: Leaks, Lies, and Libel in Drew Pearson’s Washington (New York, NY: Oxford University Press). 367 pp., $34.95.

AS A native Washingtonian in a politically aware family—my paternal grandfather was a friend of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s secretary of state, former Tennessee senator Cordell Hull, a frequent target of the columnist Drew Pearson’s invective, and my maternal grandfather was a prominent attorney who was a legal advisor to the formidable socialite “Cissy” Patterson, the proprietor of the Times-Herald, the dominant morning paper in the nation’s capital, but playing second fiddle in those days to the solid, staid, all-too-respectable Evening Star—I was already aware as a child of the competition for the spotlight among the city’s newspapers and the leading role played by Pearson. Placing a feeble third in the journalistic sweepstakes was businessman Eugene Meyer’s modest morning paper, The Washington Post. Most journalistic insiders at the time would have laughed out loud at anyone who predicted that, by century’s end, both the Times-Herald and the Evening Star would be faint memories and the Post a paper of national stature, surpassed only by The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal. As it happens, Pearson briefly was married to Patterson’s fetching daughter, and the Times-Herald became the first Washington newspaper to carry his column, which later migrated to the Post, where it was relegated to the comic pages. But while it appeared in the Times-Herald, my grandfather, Rudolph Yeatman, would often receive late-night calls asking him to vet a Pearson column—or one of Patterson’s own feverish editorial fulminations—for libel potential just minutes before press time, yet another reason I was aware of Pearson’s impact from early childhood.

It was thus with no small measure of interest that I turned to The Columnist, historian Donald A. Ritchie’s engrossing new biography of Drew Pearson. A muckraking left-wing columnist and radio commentator, Pearson is largely forgotten today. In his lifetime, however, he was arguably the most feared, loathed, and influential American journalist of his generation, unique then and never really equaled since. Perhaps the only thing that Pearson’s fans and detractors could agree on was that he was truly one of a kind, something for which the latter group was probably deeply thankful.

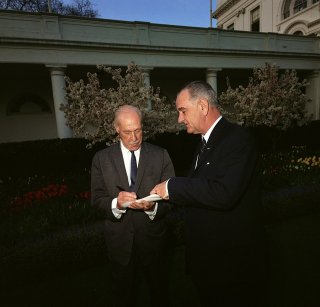

TO THOSE of us old enough to remember some of his baser performances, Drew Pearson was more of a calumnist than columnist, a man who carefully selected the muck he raked and the targets he threw it at, driven by a personal agenda rather than a clear sense of right and wrong. For some mysterious reason, Pearson’s sexual, financial, and legal exposés—both true and false—almost always targeted conservatives and anti-communists while ignoring the same kind of misbehavior at the hands of “progressive” politicians and other personal favorites he tolerated or lavished with praise. Thus, Pearson turned a blind eye to President John F. Kennedy’s scandalous private life and ignored the long record of political and personal corruption surrounding Lyndon B. Johnson. Such was the usually hard-boiled columnist’s susceptibility to LBJ’s manipulative skills that for a time Pearson actually deluded himself into believing that Johnson might make him his secretary of state.

If he had, it would not have been on the basis of two of Johnson’s Democratic predecessors’ opinions. FDR branded Pearson a “chronic liar” while Harry S. Truman simply dismissed him as an “S.O.B.” From across the Atlantic, Winston Churchill joined the chorus and moved the criticism up a notch, calling the columnist “the most colossal liar in the United States.”

Nor did Pearson’s journalistic colleagues rate his integrity very highly. In 1944, Ritchie informs us, “the Washington press corps grudgingly voted him the Washington correspondent who exerted the greatest influence on the nation, giving him twice the votes of Walter Lippmann [the most prestigious, respected national columnist at the time].” In the same poll, however, his colleagues placed Pearson at the bottom of the heap when it came to accuracy and even-handedness.

A case study of his modus operandi helps explain why. In a pre-publication article, Ritchie described how, in 1934,

General Douglas MacArthur sued Pearson for a column that charged him with using his father-in-law’s influence to win promotion to major general over more senior officers. Pearson got that story from MacArthur’s ex-wife, but she would not repeat in court what she had said at dinner. MacArthur only agreed to drop the suit after Pearson obtained the general’s love letters to his mistress.

Exactly what is going on here? Pearson, a Quaker who had avoided service in World War I, takes a cheap shot at MacArthur, who had distinguished himself under fire as chief of staff of the much-decorated “Rainbow Division.” The latter had, indeed, become the youngest major general in the U.S. Army by being promoted over the heads of a number of older mediocrities with greater seniority. But it was on the basis of his outstanding wartime record and a remarkable peacetime career that began with his graduation from West Point at the top of his class and included service as an outstanding superintendent of his alma mater. The cheap shot itself is based on an alleged private conversation with MacArthur’s embittered ex-wife at a dinner party. There is no supporting evidence, and the ex-wife refuses to corroborate Pearson’s story in court. So, Pearson manages to get his hands on private correspondence between MacArthur and an alleged mistress. He then uses the letters, shakedown fashion, to “persuade” MacArthur to drop his libel suit. Not exactly journalism at its finest.

It is entirely possible that MacArthur did, indeed, have a mistress. I can remember my late father, a second-generation Washingtonian, talking about a rather louche Washington apartment building on 16th Street where senior military brass who had acquired “exotic” oriental mistresses during service in the Philippines between the world wars housed their paramours. Built in 1920, the building’s official name was “The Chastleton,” but it was popularly referred to in those days as “The Riding Academy”—and Douglas MacArthur was rumored to be one of the riders. But even if this was the case, the use Pearson made of purloined or purchased personal correspondence to dodge a libel action was reprehensible at best, outright blackmail at worst. For Pearson, however, it was pretty much business as usual.

Ritchie explains, “Though Pearson aimed for the truth, the pressure of daily deadlines meant sometimes settling for less than the whole truth. When challenged, he occasionally found he could not substantiate a claim…” One is reminded of the humorous tag attached to the title of German rocket scientist Wernher von Braun’s postwar memoir emphasizing his role as a pioneer NASA space scientist and downplaying his work developing the Nazi flying rocket bombs: “I Aim for the Stars … But Sometimes I Hit London.”

AN EVEN more glaring case of journalistic abuse took place a generation after the MacArthur episode. In 2010, Mark Feldstein published a book entitled Poisoning the Press: Richard Nixon, Jack Anderson, and the Rise of Washington’s Scandal Culture. In a National Public Radio interview touting his book, Feldstein described how, after Nixon was elected vice president in 1952, Pearson and Anderson, his chief “leg man” and later co-writer,

...published a false story based on a forged document that claimed that Nixon was getting payoffs from Union Oil, one of the biggest oil companies, now Chevron, and it turned out to have been a fraudulent document, distributed by the Democratic National Committee.

And Pearson and Anderson didn’t just base their story on this pre-Trumpian “phony dossier,” Feldstein continued. They also “worked behind the scenes, hand-in-glove with Democrats, to orchestrate congressional hearings to try to keep Nixon from being seated as vice president.” Feldstein concluded,

Nixon’s paranoia goes back to the very beginning, and the paranoia that would ultimately bring his destruction in Watergate had some basis in fact. And it goes back to, among other things, this forged memo that Jack Anderson and Drew Pearson publicized.

In the same interview, Feldstein recounted a 1958 bugging operation that Anderson engaged in on behalf of the column. It reads like a virtual mini-Watergate incident, but it took place fourteen years before the actual Watergate break-in and the perpetrator got off Scot-free: “…in 1958, Anderson was caught red-handed with a Democratic congressional investigator, bugging [the premises of a wheeler-dealer suspected of corrupt influence peddling].”

Anderson managed to beat the rap

...[b]ecause he was with a congressional investigator [and] he argued that he was just there as a reporter covering the story. In fact, behind the scenes, he was really the principal mover and shaker. And, indeed, they could have nailed him on perjury because he did, in fact, perjure himself when asked under oath where he got the bugging equipment. He feigned amnesia, as he later admitted … in some oral history interviews.

Ritchie’s biography is conscientious, informative, fast-moving, and generally well-researched, and he makes a serious attempt to place his subject in historical perspective. But, too often, he is either incredibly naïve or willfully suspends disbelief when it comes to his hero. Time and again, he simply takes Pearson at his very dubious word, ignoring or downplaying his subject’s flagrant disregard for the truth. The reason for this may be revealed—wittingly or unwittingly—in the opening sentence of the opening section of his book when the author begins his “Acknowledgments” with the following words: