Trying Harder Is a Bad China Strategy

By treating competition as a means rather than a defining feature of great power relations, the Biden administration’s China strategy avoids confronting any tradeoffs.

In a speech on May 26, Secretary of State Antony Blinken outlined the Biden administration’s strategy on China. China, not Russia, he reaffirmed, constitutes the greater long-term threat to U.S. national interests, because it is “the only country with both the intent to reshape the international order and, increasingly, the economic, diplomatic, military, and technological power to do it.” “Beijing’s vision would move us away from the universal values that have sustained so much of the world’s progress over the past 75 years,” he warned.

The administration’s strategy to meet this challenge is “invest, align, compete”—a strategy to invest in American competitiveness and innovation, align U.S. efforts with allies and partners, and compete with Beijing to safeguard U.S. interests and the rules-based order. This amounts to little more than “trying harder.” But this is not the “unipolar moment.” The old primacy playbook no longer applies. An era of multipolarity requires reckoning with the limits on American power and influence and accepting strategic tradeoffs.

The Biden administration’s strategy calls for investing more in the development and application of cutting-edge technologies and advanced manufacturing to sharpen America’s competitive edge. But the object of such spending, despite Blinken’s denial, is the same as that of the previous administration. The Biden administration has embraced Trump-era economic “decoupling” to reduce U.S. dependencies on Chinese imports and supply chains. For this decoupling strategy to work, Washington would need to draw other countries that have substantial trade and investment ties with China into an alternative U.S.-led economic bloc, but few countries seem prepared to follow suit. European and Asian trade experts warn decoupling from China would be too costly, as it would undermine the international competitiveness of their companies and slow economic growth. “Being able to compete in China is a ticket to competing in the global market,” explained a Japanese executive. Nor is it obvious what incentives U.S. policy will provide to convince key economic actors to rethink their approach. With no appetite to ink new trade deals, since walking away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), Washington comes empty-handed.

The Biden administration’s strategy to align more closely with allies and partners in order to counter China faces serious challenges. The Biden administration overestimates its power and influence to organize a counter-balancing coalition against China. At the height of its power, the United States expected its allies and partners to quietly go along with its preferred vision of the world order. Today, a multipolar world gives them more strategic options and reduces Washington’s leverage over them. U.S. allies and partners prefer to remain on good terms with both Beijing and Washington, hedging between China as a trading partner and the United States as a security partner. But in a region where, as former Secretary of State John Kerry often said, “foreign policy is economic policy, and economic policy is foreign policy,” Washington needs to get back in the trade game if it wants to give countries in the region incentives to counter Chinese influence.

We should also pay more attention to what countries do, not merely what they say. Regional leaders express growing concern about Chinese intentions, but defense spending by these U.S. allies and partners remains anemic. Even Japan and Australia, two of China’s most vocal regional critics, respectively spend a paltry 1.3 percent and 2.09 percent of their GDP on defense annually. Compare that to the over 3 percent of GDP the Biden administration intends to spend on defense. U.S. allies and partners have limited military capabilities to bolster deterrence, casting serious doubt on the willingness of U.S. allies and partners to put their resources behind U.S.-led defense initiatives. Trying harder will not make the administration’s alignment strategy any more workable.

Still, the White House wants to commit the United States to new Cold War with China. Though Blinken was quick to dispel this notion—“We are not looking for conflict or a new Cold War”—the China strategy that he detailed threatens to produce exactly that. It casts the future as a choice between alternative visions—America’s vision for a rules-based order or Beijing’s expansive authoritarianism—and asks countries to choose a side. This zero-sum framework is a recipe for relentless competition and overextension, obliging Washington to needlessly match or counter every Chinese action—however peripheral to U.S. national interests. It is also dangerous, raising the risks of an escalation into conflict.

Above all, competition itself is not a strategy. It offers only a description of the strategic environment. And it is hardly a novel one. Great power competition is as old as the Westphalian system itself—and our age is no different. Strategy, however, requires a theory that links means to ends. By treating competition as a means rather than a defining feature of great power relations, the Biden administration’s China strategy avoids confronting any tradeoffs. It succumbs to the fallacy that if the United States simply tries harder, it can sustain primacy forever. But failing to come to terms with the world as it is will tragically accelerate American decline.

Kelly A. Grieco (@ka_grieco) is a resident senior fellow with the New American Engagement Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

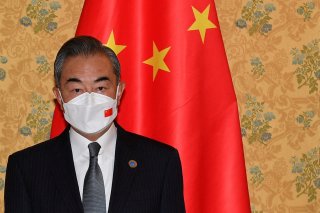

Image: Reuters.