Beyond the Taliban: Afghanistan’s Future Lies Outside Kabul

The United States must push for the decentralization of power in Afghanistan, with a focus on community autonomy and decision-making at the provincial level.

Editor’s note: In August, The National Interest organized a symposium on Afghanistan one year after the U.S. withdrawal and the Taliban takeover of Kabul. We asked a variety of experts the following question: “How should the Biden administration approach Afghanistan and the Taliban government?” The following article is one of their responses:

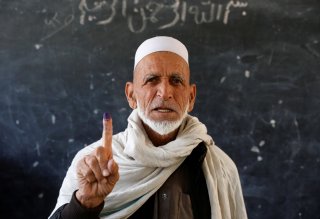

Afghanistan’s fall to the Taliban was not an ordinary regime change through an elite-led coup or a takeover of the government offices through a popular revolution. Rather, it was a total collapse of the political order, state machinery, and police and military apparatus. Further, the Taliban’s seizure of power put women's rights in jeopardy and removed them from work and public spaces, sidelined other ethnicities and religious minorities, and led to the abolition of civil liberties and freedom of speech. In short, the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan represented a social and institutional apocalypse, a complete shattering of an infrastructure that was the product of two decades of hard work, international expertise, thousands of Afghan and international soldiers’ lives, and billions of Western taxpayer dollars.

On the one-year anniversary of the U.S. military withdrawal from Afghanistan, the Biden administration's treatment of Afghan citizens and approach towards the Taliban regime shouldn’t be myopic. Rather, it must be developed against this background of a social apocalypse. An apocalyptic change requires an apocalyptic treatment, guided by strategic policy and devoid of shortsighted solutions and quick remedies. The current situation in Afghanistan is a critical juncture in the history of the country, similar to the one in 2001 that facilitated the laying out of a new democratic order, with the advantage that this time, the Taliban will not be excluded from any potential power-sharing mechanism. The United States and the international community are in the position to support a deal much more inclusive and sustainable than the 2001 Bonn Agreement, should they not fall prey to hasty engagement with or recognition of the Taliban regime for the sake of quick remedies and, possibly, election campaign goals. As similar historically critical junctures have set countries on either prosperous or miserable trajectories, this opportunity for Afghanistan could be seized to create sustainable peace and a truly inclusive system of governance. On the other hand, it could end with the consolidation of an ethno-religious regime with no respect for human and women’s rights that poses an ever-increasing threat to the future of peace in the world. Such an extraordinary opportunity calls for a more thoughtful, strategic, and patient approach, as well as more sustainable solutions on the issues of the legitimacy of power and governance in Afghanistan.

Past Mistakes and the Road Ahead

One of the main mistakes of U.S. engagement with Afghanistan in the past two decades was America’s tendency to resort to swift, military-centered measures to achieve counterterrorism goals rather than focusing on state-building and the sustainability of the democratization process in Afghanistan. One such quick measure that served these counterterrorism goals was the adoption of centralized rule in Afghanistan, a decision made without any regard for the indigenous institutions of a society that has historically been organized in a decentralized way. Afghanistan’s societal structure is closer to federalism, with the country organized along different ethnic, geographical, and cultural lines, which constitute the hubs of power and identity in regions throughout Afghanistan. Adopting a more centralized political system made it easier for U.S. officials to engage with Afghanistan’s rulers and streamlined the implementation of military goals, but it came at the cost of state-building and fostered an incompatibility between the nascent political institutions and the ethnic and social composition of the country.

The main lesson the United States can learn from its past two decades of engagement with Afghanistan is to avoid resorting to quick remedies and short-term policy goals. Instead, it should seek more strategic and sustainable solutions for the problems of governance and legitimacy in Afghanistan. One such long-neglected solution is the decentralization of power, with a focus on community autonomy in governance and decision-making at the provincial level. This would not only solve the long-standing legitimacy problem faced by almost all centralized Kabul-based rulers but would also improve accountability and efficiency in governance and eliminate the costs imposed on locals by centralized rules—either militarily or through political patronages.

The Taliban’s Fragility

The Taliban’s nature as an insurgent group and its lack of capacity and experience in governance will make time the catalyst for its demise. The Taliban’s failure in governance and its internal rivalries over rent-seeking behaviors are becoming more salient every day, building frustration among the public and even some of the movement's past moral supporters and lobbyists. Further, facing military resistance (primarily in the north) and having failed to suppress the resistance in its early stages, the Taliban regime is under great pressure, both financially and in terms of human casualties. Afghanistan’s rough geography, which once provided safe havens for the insurgent group, has now turned against it, giving the upper hand to the guerilla resistance forces in places such as Panjshir, Andarab, and parts of Takhar province in the north, adding another layer of frustration for the Taliban’s military leadership.

All these factors, coupled with a deteriorating economic situation, have placed the Taliban regime on a ticking bomb, with the group’s control over the country weakening day by day. Moreover, the Taliban’s inability to provide public services, restrictive rules such as banning girls from secondary education, and the treatment of the populace as prisoners of war have tarnished its previous slogan of being a liberator and savior. These dynamics, along with the emergence of corruption among the mostly uneducated Taliban soldiers who are appointed to important government positions, have led to mounting frustration and anger among the already struggling citizens. This calls for a more strategic approach, one that favors the long-term perspective over hasty engagement with the Taliban for the sake of short-term goals. The approach taken by the United States and other Western countries should be focused on supporting a viable long-term solution to the current social and institutional apocalypse in Afghanistan—an inclusive government with a focus on sustainability.

Moreover, the accommodation of Al Qaeda leader Ayman al-Zawahiri by the Taliban’s leadership in Kabul highlighted the Doha Agreement’s flaws and the Taliban’s lack of commitment to the deal. Both the United States and the Taliban are accusing each other of breaching the agreement, which is indicative of an ineffective and useless agreement and calls for other viable solutions for Afghanistan.

Beyond the Taliban

An alternative solution to the problem of power in Afghanistan would be for the United States to lead an international coalition in levying maximum pressure on the Taliban for its accommodation of Al Qaeda, pushing it to form an inclusive system encompassing all of Afghanistan’s ethnic, political and social groups. This could be achieved by convening an international conference and reaching an agreement similar to that of the 2001 Bonn Agreement, a necessary first step toward establishing an inclusive and decentralized new political order in Afghanistan. This necessitates reaching out to all of Afghanistan—the resistance forces, the former political elite in the diaspora, the liberals and activists, the technocrats, and the representatives of other sectarian and religious minorities.

This grand agenda is necessary, as any other short-term solutions to the current situation in Afghanistan would be ineffective and could lead to the consolidation of the current repressive, theocratic regime into one the likes of which have never been seen. If the Taliban regime succeeds, it will serve as a role model for other theocratic models of governance, emboldening other insurgent and terrorist groups in their destructive efforts and political agendas.

Tariq Basir is a Research Scholar at the Center for Governance and Markets in the Graduate School of Public and International Affairs (GSPIA) at the University of Pittsburgh where he contributes to the Afghanistan Project. He is also an Assistant Professor at the Faculty of Economics at Kabul University. He has served as an economic advisor to the Ministry of Finance in Afghanistan.

Image: Reuters.