Titanium Subs: The Navy Won't Build Them (Russia Certainly Did)

During the Cold War, the Soviet Union experimented with titanium for submarine hulls, producing the fast and stealthy Lira-class submarines. Titanium offered benefits like high strength, low density, and corrosion resistance but was challenging to source and weld.

Summary and Key Points: During the Cold War, the Soviet Union experimented with titanium for submarine hulls, producing the fast and stealthy Lira-class submarines. Titanium offered benefits like high strength, low density, and corrosion resistance but was challenging to source and weld.

-Despite the Lira's impressive speed and maneuverability, the U.S. Navy chose not to pursue titanium for their submarines.

-The high cost, difficulty in shaping, and potential risks in welding errors made titanium less appealing. The U.S. decided the effort and expense were not worth it, showcasing a rare instance of restraint in Cold War weapons development.

The Cold War was a time of accelerated and rampant military-technological innovation. The bipolar world order motivated the two superpowers, America and the Soviet Union, to invest heavily in weapons development. The result was a multi-decade spree of military spending that enhanced humankind’s destructive – and scientific – knowledge.

Jets were developed that could travel at three times the speed of sound. Missiles were developed with computer tracking systems. Spacecraft were developed that could navigate to the Moon and back. And vital to much of the Cold War weapons development was innovation in materials science. The development of radar absorbent materials, to dampen a jet’s radar signature, for example. Sophisticated tank armor. Rocket fuels.

Or, in the case of the Soviet Union, the use of titanium to build submarine hulls.

Experimenting with Titanium for Submarines

Before the Soviets began experimenting in the 1960s, titanium had never been used to build a submarine hull.

Titanium was not the most natural, or easiest choice for crafting a submarine. Sourcing titanium is difficult. And welding titanium is difficult. Steel, which was (and is) typically used to build submarine hulls, was just easier to find and easier to weld. But the Soviets were interested in titanium, nonetheless.

Titanium did have low density and high strength – properties that were, in theory, attractive to engineers hoping to make a fast and strong weapons system.

“Titanium alloy is usually stronger than steel but weighs half as [much] Brent M. Eastwood wrote in The National Interest. “It is more expensive, up to three to five times more than steel. Titanium is also less corrosive in salt water. It can handle more pressure during deeper dives – all the way down to 2,200 feet.”

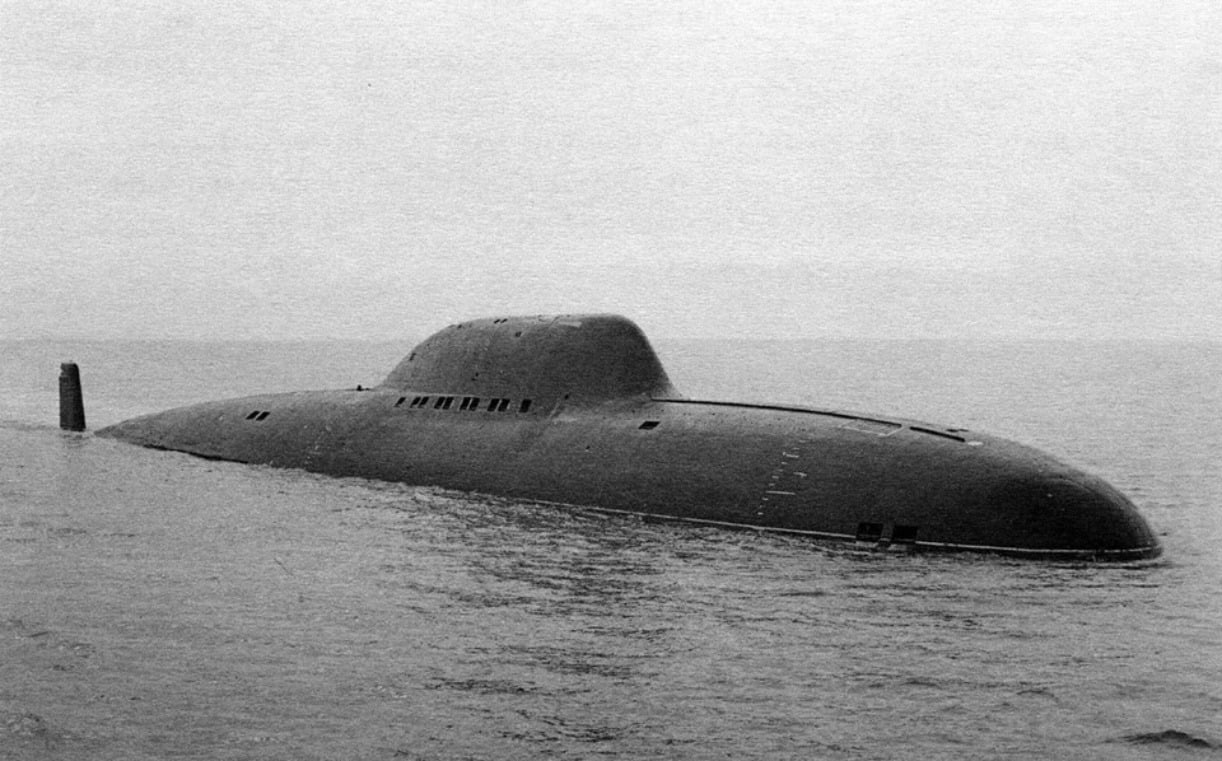

Lira-Class Submarines for Russia

Attracted to the benefits, and willing to overlook the flaws, the Soviets began building submarine hulls from titanium, starting with the Project 705 Lira.

The Lira was designed with a specific and demanding set of requirements – which the use of titanium facilitated.

The Lira was built to be fast enough to pursue any ship; to have low detectability; the maneuverability to avoid anti-submarine weapons; minimal displacement; and a minimal crew. Basically, the Lira was built to be fast, stealthy, quick, and small. A job for titanium. And indeed, the original Lira prototype weighed just 1,500 tons, with low drag. The result was an extremely fast submarine, capable of hitting speeds in excess of 40 knots. With such impressive speed, the Lira was to be used as an interceptor, kept in harbor until needed to confront an enemy submarine as quickly as possible.

The Lira “was state of the art in the 1960s,” Eastwood wrote. “It was going to reach speeds previously unattainable and be the quietest sub in the Russian navy. Titanium would be used for Lira hulls and a new lead-cooled reactor would power the ship to allow it to dive and turn quickly.” With top speeds in excess of 40 knots, the Lira “could quickly attain that speed and adroitly switch directions when needed.”

But as the Soviets soon learned, working with titanium had its drawbacks. Specifically, the Soviets found that welding with titanium was difficult, with a minimal margin of error, that “the slightest mistake during the welding phase could make the titanium brittle and less strong.”

Why Didn't the U.S. Navy Build Titanium Submarines?

Oftentimes during the Cold War, Soviet or American innovations were met with reciprocation; the two superpowers chased one another, and reacted to one another, in an ongoing duel to attain or negate a strategic advantage.

If the Soviets launched a man into orbit, the Americans raced to launch their own man into orbit. If the Americans released a supersonic bomber, the Soviets raced to develop their own supersonic bomber. And so forth. But when the Soviets released their titanium-hulled submarine, the Americans did not rush to counter. Instead, the Americans just let it slide.

“The United States was aware of the power, speed, and stealth of the Lira-class and took a close look at the titanium construction,” Eastwood wrote. But “titanium is rare and costly compared to iron. Titanium is not easy to shape either…Any mis-step by the welders would create a sub that would be dangerous to take on deep dives.”

In the end, the Americans “determined the effort and cost would not be worth it.” The result was a rare example of Cold War-era weapons development restraint.

About the Author

Harrison Kass is a defense and national security writer with over 1,000 total pieces on issues involving global affairs. An attorney, pilot, guitarist, and minor pro hockey player, Harrison joined the US Air Force as a Pilot Trainee but was medically discharged. Harrison holds a BA from Lake Forest College, a JD from the University of Oregon, and an MA from New York University. Harrison listens to Dokken.

Image Credit: Creative Commons.