Montana-Class: The U.S. Navy's Great Battleship Mistake?

Montana-class super battleships would have been nice-to-have assets for the U.S. Navy fleet during World War II and beyond. In a world of unbounded resources, that is.

Montana-class super battleships would have been nice-to-have assets for the U.S. Navy fleet during World War II and beyond. In a world of unbounded resources, that is. Everyone wants a castle of steel, a floating fortress that disgorges daunting firepower from behind walls of armor. Alas, though, no navy dwells in such a world. In the real world of finite resources, officers and officials have to weigh not just the direct costs of an implement of war but its opportunity costs and the likely return on the investment. A supersized battleship would have delivered too little extra capability beyond its predecessors to justify its costs.

Naval potentates were farsighted to cancel it. Five hulls were ordered, no keels ever laid.

That’s because the character of naval warfare was changing around the U.S. Navy by 1940, when the Navy’s General Board commissioned a series of studies meant to produce a design for superbattleships. Now, the Montana class would have been something to behold. Each hull would have bulked almost 71,000 tons compared to its 58,000-ton Iowa-class predecessors. That’s like adding a cruiser’s worth of steel to an already brawny ship of war. If built, the Montanas would have sported four 16-inch, .50-caliber three-gun turrets capable of flinging projectiles weighing up to 2,700 lbs. over twenty miles. That’s one more turret than found on board the Iowa class.

In other words, the Montanas’ broadside would have been one-third heavier and more destructive than the most fearsome artillery battery the U.S. Navy had ever put to sea.

Moreover, the Montana class would have been sheathed in enough armor to withstand its own broadside, whereas the Iowa class could not. The ability to ride out blasts from a peer battleship’s main battery is the measure of a battleship, and designers use the ship’s own armament as a proxy for the enemy’s. Those who fashioned the Iowa class deliberately skimped on armor to save weight and boost speed, resulting in a ship type better classed as battlecruisers than battleships. Unencumbered by extra plating, relatively lightweight Iowas were rated for 35 knots. The Montana class would have settled for a lower top speed, lumbering along at 28 knots in exchange for stouter shielding against gunfire, torpedoes, and bombs.

That would have been a true battleship.

And the newcomers would have been a useful adjunct to fleet operations. Contrary to common lore, it is not true that the aircraft carrier’s debut at Pearl Harbor doomed battleships to obsolescence. Battlewagons rendered yeoman service throughout World War II, chiefly by bombarding islands as part of amphibious operations. Fleet-of-foot Iowas boasted the speed and fuel capacity to keep up with carrier task forces. They bristled with antiaircraft guns, suiting them for picket duty. With even more real estate to install gunnery and sensors, Montanas would have more than matched their forebears in firepower of all kinds at the expense of slowing down the fleet by a few knots.

But air defense and shore bombardment were auxiliary missions, hardly worth the vast investment the Montana class would have demanded. For centuries capital ships had battled one another for maritime supremacy, but the era of gun battles was drawing to a close by midcentury. In short, World War II-era dreadnoughts were built for surface-to-surface engagements at a time when surface engagements were no longer the chief determinants of victory at sea. It would have been fleet-design malpractice to sluice scarce matériel, manpower, and taxpayer dollars into ever bigger, ever more elaborate, ever more resource-intensive assets that promised the fleet only ancillary value.

It’s hard to break with the past—especially when embodied in a glamour platform like a dreadnought. As one authority observes, “battleship gigantism was a thing” back in those days. And yet officialdom judged the Montana class a misfit, a throwback. Navy leaders made the right choice to discard it, and update the fleet inventory for new times.

Fitness for purpose was not the only objection to the Montana class, though. It was maladapted to the air age at exorbitant cost. Think about the costs and opportunity costs of such a venture in gigantism. Montanas would have been the largest American ships of war then afloat. A state-of-the-art Essex-class fleet carrier displaced 34,000 tons with a full load. A crude guess suggests the navy could have procured at least two Essexes for the cost and matériel that went into one 71,000-ton Montana—and carriers, unlike battleships, were war-winning implements in the 1940s. Few fleet commanders would have traded two flattops boasting precision long-range firepower—namely their complement of warplanes—for one superbattleship with twenty-mile armament, however heavy-hitting.

Plus, the navy would have needed an array of new infrastructure to support a flotilla of superbattleships. Drydocks and piers would have needed major upgrades to accommodate these behemoths. To make full use of the new class, furthermore, the U.S. armed forces would have needed to widen the Panama Canal. The beam, a.k.a. width, of Iowa-class hulls was 108 feet. That was by design. It made them narrow enough to fit through the canal’s locks, which measured in at 110 feet wide. The ability to transit the isthmian waterway let Iowas swing back and forth between the Atlantic and Pacific, bolstering their mobility. By contrast, either the hulking Montanas would have been forced to circumnavigate South America to shift oceans, or engineers would have had a major public-works project on their hands in Central America. Expanding the Panama Canal to handle a mere five ships sounds mighty wasteful on its face.

No fleet designer constructs a battle fleet to fight a type of war that is no longer relevant, and at colossal upfront and opportunity cost. No sane fleet designer, anyway.

Again, Montana-class battleships would have been nice to have. But they would have been nice to have for reasons other than their primary reason for being, namely outdueling enemy dreadnoughts. They were massively overdesigned for the secondary functions they would have performed, such as air defense and naval gunfire support. Some or all Iowa-class vessels returned to duty during the Korean War, Vietnam, and the late Cold War—testament to the value a heavy-hitting, thickly armored gun platform brings to amphibious warfare and power projection. The U.S. Navy and Marine Corps have been trying to replicate that capability—to little avail—ever since mothballing the battleships for the last time in 1992. But the sea services and Congress have also refused to let their desire to furnish the fleet with gunfire support crowd out platforms fit for this age of sea combat, such as supercarriers, destroyers, and submarines. The tradeoffs were too forbidding during World War II. They remain too forbidding today.

Letting that capability lapse may not have been a desirable move. It was—and is—the prudent move.

About the Author: Dr. James Holmes, U.S. Naval War College

James Holmes is J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the Naval War College and a Faculty Fellow at the University of Georgia School of Public and International Affairs. The views voiced here are his alone. A former U.S. Navy surface-warfare officer, he was the last gunnery officer in history to fire a battleship’s big guns in anger, during the first Gulf War in 1991.

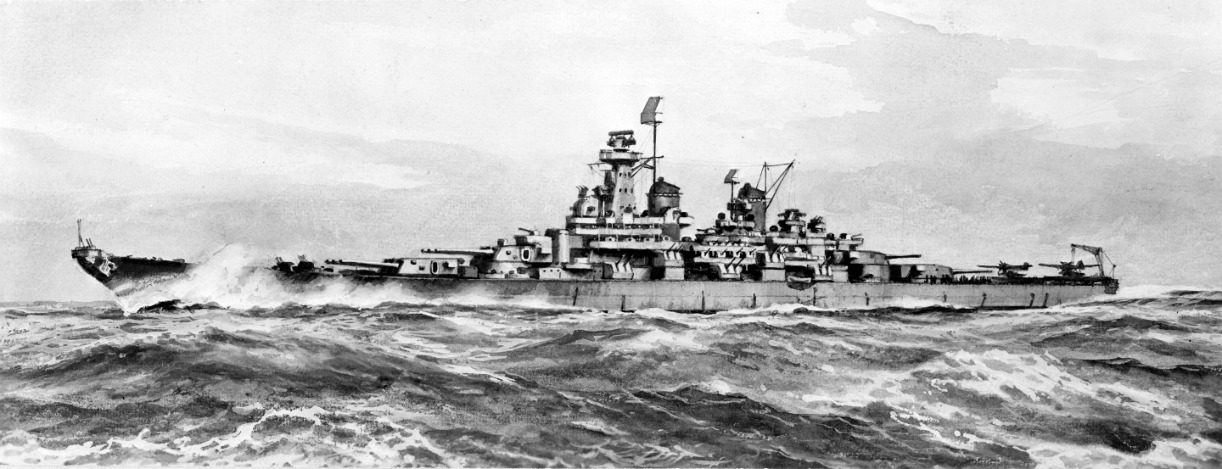

Image Credit: Main image is a Creative Commons image of an Iowa-Class battleship. All others are of possible Montana-Class battleships.