How America Should Handle Iran and North Korea

Washington must not use a one-size-fits-all approach.

Last month, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo accused Iran of depriving its people to further its influence abroad, condemned Iran for violating human rights, and urged the Iranian people to provoke regime change. Yet just several weeks prior in a statement on North Korea, Pompeo did not call for the North Korean people to overthrow the regime of Kim Jong-un and wholly omitted any mention of human rights in North Korea, even though the country is a worse human rights abuser than Iran. Why has the Trump administration dealt with these two countries so differently? The answer, which comes down to differences in each country's political system, economy, and history, includes implications for how America can achieve denuclearization in both countries.

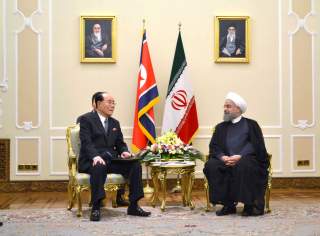

First, North Korea and Iran have different political and economic systems. Although the two countries seem to be similar in that their people live under totalitarian governments, Iran’s partial democracy allows the Iranian people to influence their government via presidential and parliamentary elections, not to mention demonstrations and strikes. Although the regime tightly controls these processes, Iranians certainly have more ability to influence their government than North Koreans do. For example, Hassan Rouhani, Iran’s current president, was elected against opposition from hardline factions because of his promise to lift international sanctions, develop his people’s livelihood, and pursue better relations with the West.

But Iran’s economic growth since the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA or Iran Deal) was signed in 2015 has been undermined by a tense political climate with the United States. The re-imposition a ban on Iranian oil exports, its primary source of income, and further sanctions, which are scheduled to go into effect in November, are directly targeted at the Iranians’ livelihoods. For example, cutting Iran off from the SWIFT system, which allows Iranian banks to transfer money internationally, will seriously undermine the Iranian economy by harming its ability to trade abroad. Indeed, Iran’s currency, the rial, has depreciated by nearly 80% since last year, raising the cost of imports and essential goods. The United States knows that its sanctions will be effective in Iran because Iranians are revolting as their economy goes into freefall. As more Iranians revolt, the pressure on the government increases and it becomes more likely to make concessions.

In contrast, North Korea is not your average tyrannical country. Although North Korea ostensibly has a democratic process for electing a legislature, this process is a farce; candidates face no competition and are selected by the state's single party. The North Korean people are forced to vote yes under surveillance or they face imprisonment without any ability to strike or demonstrate. Further, since the state's ideology brainwashes the North Korea people, they will follow any painful decisions made by their government out of fear, loyalty, or both. Thus, the effect of sanctions against North Korea, while certain to harm the people living there, is far less certain.

Moreover, North Korea is already very isolated from the world economy after decades of sanctions. Pyongyang earns its primary income from illegal sources (such as selling drugs and weapons and money laundering). This means that additional sanctions will have less of an effect on the regime's pocketbooks. North Korea remains heavily reliant on its primary trading partner, China, which comprises 91 percent of North Korea’s trade. Therefore, the effectiveness of international sanctions depends on China's participation. This is a crucial difference from Iran, which is not dependent on trading with a single outside state. This notable difference should be taken seriously in dealing with both countries.

Second, each country poses a different military threat to the United States and its allies. North Korea already has nuclear weapons and an advanced ballistic missile arsenal that includes missiles capable of reaching the United States. Indeed, North Korea has threatened many times to attack America in response to aggression from Washington. Although North Korea’s conventional military employs decrepit platforms, Pyongyang has formidable asymmetric capabilities including biological and chemical weapons, submarines, EMP and nuclear weapons.

In contrast, Iran doesn't have nuclear weapons or a missile system that can directly attack the United States. Instead, Iran's missiles can at most reach Central Europe, making the problem of Iran's nuclear capabilities an indirect threat to America, but a serious one for U.S. regional allies. The real concern is the possibility that Iran could eventually sell their nuclear weapons to terrorists, attack Israel, or use them to deter the United States while more aggressively expanding their influence in the Middle East. But these possibilities are hypothetical and can be addressed by other U.S. policy decisions.

Third, the two countries have different goals for expanding their influence as a result of the nuclear negotiations. The negotiations with Iran thus far have given Tehran a chance to extend its ideological influence in the Middle East. After sanctions were lifted, Iran sought to use its oil revenue to provide weapons and money to the Syrian President Bashar al-Assad's government forces and to militants and terrorists in Iraq and Yemen. Surely, with the impending victory of the Assad regime, Iran will retain an influential role in the country from which it can threaten Israel and the Arab Gulf states. Israel, in particular, has also been concerned by Iranian support to Hamas and the Lebanese Hezbollah, as well as Iran's efforts to militarize the Syrian side of the Golan Heights. That Iran's influence is embedded throughout the region makes addressing Iran's nuclear program all the more complicated and pressing. Any agreement that legitimizes Iran's nuclear program or gives it a windfall of cash without taking into account these factors will strengthen its regional influence and prestige.

Unlike the negotiations with Iran, successful denuclearization in North Korea would result in the growth Pyongyang's political and economic influence in East Asia. However, the critical point here is that North Korea doesn't want to export its ideology to other countries like Iran. North Korea's national ideology is only confined to the Korea Peninsula, and Kim Jong-un just wants regime stability, rather than expansion. For that reason, negotiations with North Korea will bring many direct and indirect benefits to the United States. For instance, ending North Korea's nuclear weapons program will be helpful in reducing tensions, and the correspondingly vicious arms race, in East Asia. By alleviating a significant threat to Japan and South Korea, interstate relations in the region will likely become more stable and secure. In addition, America can reduce the need for North Korea to illegally sell weapons and advanced technologies abroad by opening up legal means for Pyongyang to earn foreign currency, eliminating further threats to Israel and other states.

Because of the above differences between Iran and North Korea's nuclear ambitions, the United States should deal with each differently while pursuing denuclearization. But before suggesting a process tailored to these two nuclear negotiations, it is essential to define the metrics for success in both countries. For the United States, what is most important in North Korea is eliminating the nuclear security threat while regarding Iran it is blocking its growing regional influence and potential nuclear proliferation.

In the nuclear negotiations with Iran, America should remember that the Iranian people are the regime’s greatest weakness. By provoking the Iranian people through targeted economic sanctions, the United States can create leverage to use as a bargaining tool. However, in North Korea, America should separate the political issues and human rights problems. As some people have observed, the United States is not pressuring North Korea on human rights because it is likely to ruin the negotiations rather than create leverage.

Second, the United States should focus on calculable factors in its negotiations with Iran. America already knows the locations of Iran’s nuclear facilities, how many centrifuges Iran has and how much uranium the country is enriching and has stockpiled. Seeking limits on these factors is both more feasible and verifiable than trying to address abstract and complex concepts such as blocking Iran’s “malign influence” in the region.

In contrast, the United States doesn’t have accurate information on the location or number of North Korea’s nuclear facilities or weapons. These uncertainties greatly complicate the negotiating process with North Korea. Given these circumstances, America should seek a more detailed agreement that starts with an understanding that complete, verifiable, irreversible denuclearization (CVID) is almost impossible. North Korea's sizeable domestic uranium deposits, cadres of unknown scientists, and hidden facilities make a permanent solution infeasible. Furthermore, North Koreans have no access to the internet and have been brainwashed by their government, which dramatically complicates the ability of the United States to gather intelligence or flip human sources as it did with Iranian dissidents. For these reasons, even if North Korea sent their nuclear warheads out of the country, it could restart its nuclear program again whenever it wants. Hence, the United States should be satisfied with an outcome of North Korea giving up its nuclear weapons capability and abandoning its intercontinental ballistic missiles. But the United States needs to make some conditions in the negotiation. Specifically, if CVID is achieved, but America finds out there is another nuclear facility or that Pyongyang has restarted its program, Washington should declare all these all negotiations invalid and reinstate the sanctions against North Korea immediately.