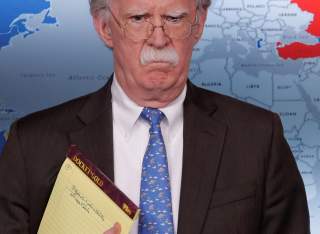

Trump Makes the Right Call: Bolton Out

In each of his positions in government, Bolton has made the world a more conflictual place and the United States a more isolated and despised country.

That President Donald Trump will soon have his fourth national security adviser in less than three years reflects the lack of strategic sense underlying the president’s foreign and security policies. When policy is more a matter of applause lines and appealing to a domestic political base than of implementing a coherent view of America’s place in the world, then seeing whether the president and the job candidate share the same coherent view is not part of the hiring process. Trump’s hires have not brought about anything like Henry Kissinger and Richard Nixon meeting at the Pierre Hotel after the latter’s election victory in 1968, with the president-elect determining that he and the Harvard professor shared a realist way of thinking about how the world worked and America’s place in it.

Trump’s filling of the national security adviser’s position has been a scattershot response to diverse needs and impulses. Michael Flynn clearly was never properly vetted. H. R. McMaster had the attraction of wearing a general’s uniform without Flynn’s baggage. But Trump evidently did not anticipate how he would tire of McMaster’s dutiful reminding his boss of the way the world really works, even when that way does not fit into a slogan. The appointment of John Bolton seemed to many as the oddest of any of these three hires, given how this uber-hawk’s views appeared to clash with Trump’s campaign rhetoric about staying out of wars. But Bolton offered bureaucratic savvy and the opportunity to win points with hawkish parts of Trump’s Republican base.

The single biggest factor in getting Bolton the job was Sheldon Adelson, whose weighty political checkbook has won him much influence over Trump’s policies. The policies that by far have mattered most to Adelson are any that deal with Israel or are important to the right-wing government of Israel. Adelson and Bolton both have openly advocated bombing Iran, which is music to the ears of the ultra-hardline policy toward Iran favored by Benjamin Netanyahu’s government. It was this sort of stance by Bolton that made him Adelson’s favored candidate for the White House job.

It possibly is no coincidence that the firing of Bolton comes shortly after a sharp public falling-out between Adelson (along with his wife, Miriam, a dual Israel-U.S. citizen) and Netanyahu. This altercation, which surfaced during an investigation of corruption allegations against Netanyahu and evidently has involved the prime minister becoming especially assertive in trying to direct the editorial practices of Israel Hayom, the free-distribution newspaper Adelson owns, is a marked and surprising departure from what had been a close political and financial partnership between the Adelsons and Netanyahu. Trump may believe that with this split, he still has his Israeli bases covered despite ousting Adelson’s man from the West Wing.

More fundamental to Trump’s calculations, however, was his realization that Bolton’s determination to wreck deals clashed with Trump’s desire to make deals. This has been the case on several fronts. It is true of North Korea, where Bolton’s wrecking career began as an undersecretary in the George W. Bush administration, when Bolton boasted of his role in killing the earlier Agreed Framework dealing with the North Korean nuclear program. Trump reportedly had already sidelined Bolton from a further major role in policy toward North Korea. He also partially sidelined him on policy toward Afghanistan, although Bolton may get the last word there given that it now looks, according to the president, that a prospective agreement with the Taliban is dead.

The major foreign-policy issue on which Bolton’s departure is likely to make the biggest difference is Iran. Bolton has always wanted war; Trump has increasingly indicated that he wants a deal. It had to be clear to the president that any effort to reach such a deal would be subject to sabotage efforts by Bolton every inch of the way. Iran is also an issue where current policy is manifestly failing, with the “maximum pressure” campaign resulting only in harder line Iranian postures regarding nuclear matters, activity in the Middle East, and domestic Iranian politics. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo has been Bolton’s maximum pressure partner in all this, but Pompeo’s first priority is to stay in tune with the president. With Bolton gone, the president’s, and thus Pompeo’s, tune may change.

President Trump has done the right thing by firing John Bolton. In each of his positions in government, Bolton has made the world a more conflictual place and the United States a more isolated and despised country. This certainly has not made the country safer. One indication of how much Bolton’s policies have been at odds with U.S. national interests is that he still believes that the disastrous offensive war in Iraq was a good idea.

It is impossible, of course, to gauge just how much Bolton’s departure represents an improvement until a new national security adviser is announced. That appointment will be all the more important because of another part of Bolton’s legacy, which has been to destroy the policymaking procedures of the National Security Council and circumvent the national-security bureaucracy in general, and to make policymaking a more irregular and closely held game of maneuvering to influence the president. A previous time when foreign policy was in large part run out of the national security adviser’s vest pocket was when Kissinger had the job, and to the extent it worked it was only because of the intellect and talents of the man wearing the vest. Kissinger himself recognized how shaky the arrangement was and recommended in his memoirs against any attempt to repeat it. What President Trump could use most right now is a national security adviser who will restore an orderly policymaking process in which policy options are carefully considered, from all angles and by everyone in the executive branch with relevant responsibilities. But given Trump’s own operating style, that is probably not going to happen.

Paul R. Pillar is a contributing editor at the National Interest and the author of Why America Misunderstands the World.

Image: Reuters