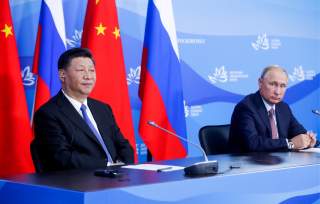

America Has Leverage with China that It Lacks With Russia

And Washington should use it to tilt great-power politics in its favor.

At present, U.S. foreign policy confronts a difficult dilemma concerning China. There is a growing consensus in Washington that China is America’s primary strategic competitor, if not adversary. However, most of Washington’s other major foreign-policy challenges, Iran, North Korea, Venezuela, withdrawing from Afghanistan and an intensifying strategic contest with Russia, are rendered more manageable if Washington preserves a working relationship with Beijing.

A Paradigm Shift on China

The Trump administration has now settled on a strategic approach towards Beijing, which Robert Sutter characterizes as a “broad hardening of U.S. defense, internal security, and economic operations against China.” This is a departure from Donald Trump’s initial stance, which was transactional, focused primarily on stemming perceived U.S. economic losses resulting from predative Chinese behavior. On the campaign trail, Trump zeroed in on what he saw China doing to America: trade imbalances due to insufficient market reciprocity and (alleged) currency manipulation; he noted the eroding U.S. competitive advantage resulting from years of intellectual property theft and forced technology transfer. In his characteristic hyperbole, candidate Trump slammed China for perpetrating “the greatest theft in the history of the world.” This strain of thought persists in the administration with Trump advisors’ (Peter Navarro most vociferously) mantra of “economic security as national security.” However, since late 2017, Trump’s approach has morphed from striving to inoculate the United States and its allies from detrimental Chinese behavior to a sweeping crusade that proactively seeks to counter Chinese political influence and economic penetration across the world. This is manifested most dramatically in the high-tech sector, where (per Sanger et al) the United States has embarked on a “stealthy, occasionally threatening, global campaign to prevent Huawei and other Chinese firms from participating in the most dramatic remaking of the plumbing that controls the internet [development of 5G networks]” since its creation. Clearly the U.S. squeeze on Huawei is starting to chip away, at least at its wireless infrastructure operations, with the telecom giant recently suffering a 1.3 percent drop in its networking business.

The United States lacks a telecommunications company willing or able to compete with Huawei or ZTE in 5G network infrastructure development. As a result, competition to build 5G infrastructure in the United States and other countries that block Chinese telecoms, is falling to the big Scandinavian telecoms (Ericsson, Nokia). South Korea’s Samsung, a latecomer to the race, is also mounting a strong push to up its share of the 5G market. Importantly, for Ericsson, Nokia and Samsung, 5G is solely a business venture. To be sure, Huawei and ZTE are publicly traded companies operating based on profit-seeking business motives. However, due to their deep links to the Chinese state, Huawei or ZTE laying the wiring for 5G networks would give Beijing an exploitable strategic advantage that boosts key elements of national power: cyberwar, intelligence gathering and information operations.

There is a certain cold-blooded logic to U.S. efforts to exclude Huawei and ZTE from the 5G network market. The high-tech sector is a salient area where the United States and its allies hold a substantial, yet narrowing, comparative advantage over China, which it is in Washington’s interest to preserve. However, in the context of the Trump administration’s overall China policy, particularly, tough actions on trade and investment and enhanced support for Taiwan, the counter-Huawei/ZTE campaigns will only be seen by Beijing as part of a U.S. attempt to go for the jugular, to bring China to its knees.

Unfortunately, this is exactly the direction the Trump administration is trending. Based on conversations with former senior administration officials, Harry Kazianis observes there is a line of thinking prevalent in Trump’s foreign-policy team that the United States should strive to “crush” China, to “drive them into the ground.” This aggressive attitude is premised on the misperception that Beijing harbors ambitions not only to dominate Asia, but eventually the world. While Sinologists generally concur that China seeks to resurrect its historical sphere of influence in East Asia; most see scant evidence that Beijing seeks world domination. This new adversarial approach is a fundamental departure from the China policy that the United States has followed for the past four decades wherein Washington sought to correct Chinese behavior that diverged from international norms, but refrained from making such an explicit and sustained effort to cut China down to size. Then-Deputy Secretary of State Robert Zoellick’s “Responsible Stakeholder” speech in 2005 famously epitomized this traditional “rules-based order” approach to China.

It would be difficult, but immensely beneficial for Washington to shift to a more subtle China policy, which combines decoupling in the high-tech sector with sustaining interdependence across the rest of the U.S.-China economic relationship. Japan, which is deeply economically interconnected with China, has shown it is possible to go this route. Tokyo has quietly sought to quarantine its high-tech infrastructure from Chinese penetration through measures such as “data reciprocity, strategic investment protections, and blocking Chinese participation in Japanese 5G infrastructure development.” At the same time, Tokyo remains deeply committed to maintaining robust trade ties, particularly as China accounts for nearly all of the limited export growth on which Japan’s economic health depends. Last October, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, who has since 2012 overseen a hardening of Japan’s own position towards China, inked a series of economic cooperation agreements with Chinese leaders during his visit to Beijing.

The United States should consider quietly undertaking its own China policy shift that brings its “get tough” strategy more in line with Tokyo’s nuanced approach. This would complement Washington’s efforts to deepen security ties to allies and partners that are economically interlinked with China, but share the United States’ aim of hedging and balancing growing Chinese military power in the Asia-Pacific region. To provide additional ballast, Washington should proactively seek to engage Beijing on pressing international security issues such as arms control and WMD proliferation.

There are also compelling systemic reasons to preserve a working bilateral relationship. John Negroponte, director of national intelligence under President George W. Bush, has asked, “Do we want to preserve one world, one system? The relationship with China is critical to that . . . clearly, if there is one world, two systems, it’s going to be much harder to deal with global issues.” This underscores that Washington lacks the luxury of dealing with China in isolation. Certainly, if the United States were to concentrate the lion’s share of its strategic focus and resources on China, as it once did on the Soviet Union, there is little doubt that a “pushback” or neo-containment strategy would stand a good chance of success. However, the United States’ China policy does not exist in a vacuum, but rather intersects with other intractable foreign-policy challenges: Iran, North Korea, Venezuela, drawing down in Afghanistan, and an intensifying, parallel strategic rivalry with Russia. On all of these issues, having a working relationship with Beijing serves Washington’s interests. However, as long as Beijing perceives an all-out strategic rivalry with the United States lurking over the horizon, China will derive utility from the U.S. enmeshment in nettlesome regional struggles with difficult middle powers such as Iran and North Korea.

The perceived inevitability of U.S.-China strategic rivalry also reinforces Beijing’s receptivity to Russian entreaties to cooperate more closely to keep the U.S. strategically off-balance. The United States can considerably improve its strategic situation if it finds a way to put some daylight between China and Russia. For Trump, a good start to loosening the Sino-Russian entente would be cutting a deal with Xi Jinping on trade.

The Scalene Strategic Triangle

A straightforward approach to triangular diplomacy suggests that the United States, as the strongest power in the triangle, should seek to break its ongoing impasse with Russia, the weakest power, in order to keep its closest near-peer challenger, China, off balance. Putting aside the obvious domestic political obstacles (in both the United States and Russia) to U.S.-Russia rapprochement, there is the difficult reality that Washington lacks much positive leverage over Moscow. There is little economic complementarity between the United States and Russia. If anything, there are competitive drivers: Russia’s biggest exports are by far hydrocarbons, which following the shale gas revolution, also rank among the top U.S. exports. Trade ties are very modest with the United States accounting for 4.5 percent of Russia’s total export value in 2017, well behind China at 11 percent, the Netherlands at 8.1 percent and Germany at 5.8 percent. Trade the other way is even more meager with less than one percent worth of U.S. exports Russia bound in 2017. As a result of its lack of “carrots,” Washington relies primarily on its considerable negative leverage, “sticks” (military pressure, sanctions and restricting Russian access to the dollar-based international financial system) to deal with Moscow. While these punitive measures hurt Russia by weakening its economy, they also reinforce Russian intransigence towards the United States.

By contrast, Washington has far more carrots to deploy with Beijing. China remains economically reliant on the United States as a market, which took in a fifth of total Chinese export value in 2017), and as a source of advanced technology. If you think otherwise, revisit ZTE’s near death experience from U.S. sanctions last year, or recall the U.S. full-court press versus Chinese telecoms detailed earlier in this article. Of course, the United States is itself also vulnerable to Chinese retaliation, which has the ability to inflict reciprocal, although not necessarily commensurate, economic hardship (e.g. retaliatory Chinese tariffs have seriously hurt the U.S. Agricultural sector).

As Western sanctions ramp up, Russia is becoming increasingly, economically reliant on China, which provides Beijing with substantial leverage over Moscow. For its part, China still depends on Russia for access to some advanced armaments and as a diplomatic partner with which to counter the West, particularly in the UN Security Council.

Due to these imbalances, the U.S.-China-Russia strategic triangle is now more disadvantageous to the United States than at any time since the early 1950s. As former People’s Republic of China Vice Foreign Minister Fu Ying observes, U.S.-China-Russia trilateral relations “currently resemble a scalene triangle in which the greatest distance between the three points lies between Moscow and Washington.” China now occupies the envious “hinge position” of having better relations with the other two poles than they do with each other, which Nixon and Kissinger exploited to great advantage. As a result, Angela Stent surmises that “If any country has a card to play, it is China.”

Proponents of Kissinger-style triangular diplomacy often forget that an underlying driver that engendered Chinese receptivity to Nixon’s overtures was Beijing’s long-simmering bitterness over intensive diplomatic engagement between Moscow and Washington dating back to the Khrushchev-Eisenhower summits of the 1950s. No one at that time would have claimed that the PRC was stronger than the Soviet Union, but after Stalin, the United States possessed leverage and a working relationship with the more pragmatic leaders in Moscow (particularly on managing the precarious nuclear arms race) that Washington lacked with the revolutionary Maoists in Beijing. Now, the situation is effectively reversed. The United States has substantial leverage over China, and Chinese leaders are more pragmatic than their Russian counterparts. While Putin is obviously very different from Mao, like 1950s and 1960s Mao, he defines Russia and Russian power primarily in opposition to the United States.

Finally, if Trump and Xi are able to achieve some kind of modus vivendi on trade and other economic issues, then it will deeply unsettle Russia. Moscow knows that at the end of the day, despite all the Putin-Xi bonhomie, the economic relationship with the United States is salient to China’s national interest. A prime example of this, is that as Russia has faced increasing U.S. sanctions since 2014, Chinese banks have been “largely unwilling to provide credit to Russian entities under U.S. sanctions for fear of the consequences for their dollar-denominated transactions and dealings with U.S. firms.”

The dawning realization in Moscow that Russia risks becoming a chip at the U.S.-China bargaining table may eventually spur Putin to rethink his policy of permanent confrontation with the United States. Perhaps then, conditions will be right for an American mission to Moscow akin to Nixon’s 1972 visit to Beijing. Until then, the real opening in the strategic triangle is in Beijing, not Moscow.

John S. Van Oudenaren is assistant director at the Center for the National Interest. Previously, he was a program officer at the Asia Society Policy Institute and a research assistant at the U.S. National Defense University.

Image: Reuters