The Army's Role in Israeli Politics

Mini Teaser: Has Israel’s military elite distorted Israeli politics—and rendered peace impossible—through its aggressive view of the world?

Ben-Gurion, on the other hand, Tyler writes, “believed in Zionist exceptionalism, and so he and the youthful sabra military establishment stood to fight.”

This is the core of Tyler’s thesis. He asserts, “Here was the essential tension in Israeli political culture: the clash between Sharett’s impulse to engage the Arabs and the military establishment’s demand to mobilize for continual war.” He summarizes this way: “Early Zionist notions of integration and outreach were undermined by a mythology that Israel had no alternative but war.”

But there is no real reason to believe that a combination of outreach, the UN Charter and the Eisenhower administration was going to resolve Israel’s problems with larger, mostly unstable neighbors led by military officers who were itching to take revenge for their defeat in the 1948 war. Nor was President Eisenhower, in those very different years, likely to come to the defense of Israel if it were being overrun. As Tyler himself writes, in 1956 Ben-Gurion told Eisenhower’s secret representative, Robert B. Anderson, “I do not believe that you would go to war against Egypt if they attacked us.”

Tyler simply puts too much weight on Sharett versus Ben-Gurion as the key to the formation of the Israeli mind-set and the supposed victory in modern Israel of Sparta over Athens, as Tyler would have it. There were not two equal roads diverging in the Israeli desert of the early 1950s, and a good case can be made that Ben-Gurion’s aggressiveness kept Israel alive at a delicate time.

Sharett may have been the right man at the wrong time. But in many ways Sharett, a man of diplomacy, was a weak leader and a failure. He presided helplessly over the fallout from the scandalous Lavon Affair, in which Israeli secret agents in Egypt planned to blow up Egyptian, American and British targets to make the Nasser regime seem unstable but about which he as prime minister was kept unaware. Later he proved unwilling to use this fiasco to confront his opponents.

Sharett was an inadequate leader who did not command the confidence either of the army or of his mentor Ben-Gurion; he was outmaneuvered and in some sense paralyzed by the new pan-Arab nationalism and the attraction of Nasser, which was clearly a danger to the new Jewish state.

SIMILARLY, TYLER tries to draw a broad line between the country’s military elite and the rest, and from time to time he seeks to draw a slightly more narrow distinction between a supposedly warlike “sabra” mentality of the native-born Israelis and the more dovish and ineffectual immigrants. But of course that’s a distinction with very little value, since over time nearly everyone in the military is native born. The most numerous new immigrants are Russians, who are more Likud than Likud—more anti-Arab and more willing to fight it out than most of the native-born or sabra population.

The military in Israel is one of the most vital institutions of the state, to be sure, and certainly the best resourced and best organized; its arguments carry great weight. Given generally universal military service, subject to complicated exceptions for Israeli Arabs and ultra-Orthodox Jews, the period that young people spend in the army tends to shape them. Those experiences also produce friends and alliances that persist through life, providing contacts throughout the society.

Young Israelis trained in military intelligence and computer work are the backbone of the country’s successful modern economy, founding companies that often get their start with military contracts. Soldiers in companies and brigades form fierce alliances, almost like tribes. The rivalry between the Givati and Golani brigades, for instance, shapes lives and friendships as well as political and business relationships. The paratroopers and the pilots of the air force have similar alliances.

And sometimes they go into politics, especially the generals, because they are among the best-educated, bravest and well-known figures in Israel. But of course they are not always very good politicians, especially in the political jungle that is the fractured Israeli system, where small parties devoted to single issues—religious education, for example, or ensuring that El Al does not fly on the Sabbath—make or break governments.

But while there is a military elite, it is hardly monolithic. There are generals on the Right and on the Left. There are heads of the intelligence services on the Right and on the Left. And in fact there are more generals, including intelligence chiefs, on the Left in Israel than on the Right. Indeed, it is the military elite, including former Mossad leaders Efraim Halevy and Meir Dagan, that has been most vocal in challenging Prime Minister Netanyahu on the wisdom of attacking Iran. But that has hardly stopped the decline of the Left in Israel.

Further, Israel’s failure to produce a lasting peace treaty with the Palestinians is hardly the sole fault of the generals or of some vague “military elite.” It is first and foremost a failure of politics, of nerve and of timing.

After all, who actually achieved the various peace treaties that Israel has managed to negotiate? A former military commander and terrorist named Begin, a former general named Rabin and a former general named Barak. The same people had their failures at peace, too, but they were hardly against the idea when they judged that the national interest demanded it. Ariel Sharon, presented by Tyler as Israel’s Mad Max, dripping with aggression and blood, may have had ulterior motives, as he certainly had strategic and political ones, but he did after all pull Israeli troops and settlers completely out of Gaza.

And when the Israeli military has had clear political orders, it has generally followed them. It dismantled the settlement of Yamit when Begin ordered it, pulled out of Sharm el-Sheikh and the Sinai, and dragged Israeli citizens and settlers out of their synagogues and homes in Gaza as well as four settlements in the West Bank—with much emotion but also with professionalism.

And of course if the political leadership orders the army to war against Iran, it will obey, however reluctantly.

Even Shimon Peres, who famously never served in the military and is considered a grand old man of the peace movement, was deeply involved in military planning as a defense aide, defense minister and prime minister. This same Peres, a contradictory and human figure, was vital to convincing France to give Israel the plutonium reactor at Dimona, vital to the beginning of the settlement movement and vital to the Oslo peace process.

DESPITE THE old phrase about defeat being an orphan, the failure to make peace has many parents. And certainly included among them are the failures of the fedayeen to get their act together under the British; the failures of the United Nations to enforce the 1948 agreement creating two states out of the British mandate; the failures of the Palestinian people—and they have become a people and deserve a nation—to seize opportunities when they arose; the failures of Palestinian leaders from Yasir Arafat to Mohammed Dahlan to Mahmoud Abbas to manage their own people and be truthful with them about what peace would require; and the failures of the Arab world to give much more than mere rhetoric to the Palestinians—especially to Abbas, when he had a legitimate democratic mandate and wanted to make peace. But the Arabs failed Arafat, too, who was loved by the Arab world when he was fighting Israel but not when he was negotiating with it.

Certainly the failures must include the Israeli settlement program, the government-supported effort to colonize what some Israelis regard as God’s land grant to Abraham and thus create “facts on the ground.” But this program was not initiated by the military; it was the product largely of the Left, including the chameleon Shimon Peres, and ignored by Israeli politicians who should have known better, such as Ehud Barak.

And among the greatest failures must be included indifferent, wavering and often contradictory American policies—led by successive presidents reluctant to challenge the power of Congress and offend the fund-raising machine that is the American Israel Public Affairs Committee (AIPAC). That reluctance continued even when Israeli leaders such as Rabin and later Barak had policies that were far more flexible than those of AIPAC and criticized the lobby for daring to oppose them.

What’s striking about these American presidents is that they have not been willing to push Israel to live up to even its own freely given promises—pledges made not to the Palestinians or the United Nations but to those presidents themselves. For example, Sharon promised George W. Bush personally that he would remove all illegal outposts created by Israeli settlers after March 2001, when Sharon took office. The pledge was written into the road map of the international quartet (composed of the UN, United States, European Union and Russia), along with the language on a settlement freeze, including “natural growth.” Sharon signed the road map. After Sharon’s stroke, Ehud Olmert was elected as his successor and said he would stand by those promises.

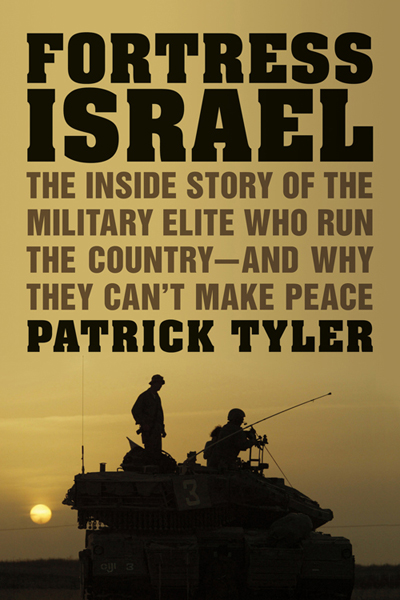

Pullquote: Tyler's book is less an investigation into “fortress Israel” and its supposed ruling military elite than a diligent and insightful history of Israel’s leaders and their military engagements.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review