The Army's Role in Israeli Politics

Mini Teaser: Has Israel’s military elite distorted Israeli politics—and rendered peace impossible—through its aggressive view of the world?

Olmert dismantled exactly one such outpost, Amona, in early 2006. He chose to do so after considerable warnings to the settlers and during the daytime. The result was a predictable conflict between settlers and the police and army, which Olmert then used as a pretext to say that it was too politically difficult to dismantle any more. When I asked him if he had no sense of shame about breaking his promises to his finest allies and lying to them as if the United States were the British rulers of mandatory Palestine, to be hustled and worked around, he bristled.

I asked him why he as prime minister chose not to enforce his country’s own laws, and he bristled again.

I said that the Israeli army dismantled supposedly illegal Palestinian houses in occupied territory, and even in Jerusalem, at will. They could do so because they acted with no warning and operations took place before dawn. Olmert then looked at me like I was an idiot who could not understand the obvious fact that he could not treat Israelis the way he treated Palestinians. Olmert, it should be noted, did not serve in the military, except in an arranged journalist job so he could have the army on his résumé. Yet it was Olmert who pressed for the most recent wars in Gaza and Lebanon.

But where was Washington on the settlement issue? Even to me it was obvious that “natural growth” could not explain the explosion in the number of Israeli settlers living beyond the Green Line—and not just in the so-called major population centers in the West Bank such as Gush Etzion and Ma’ale Adumim. Even Kurtzer, who did not like it, admits that the Bush administration was largely silent in the face of these Israeli policies.

Political dysfunction—whether Israeli, Palestinian or American—has had as much to do with the failure to finally force through a lasting two-state solution as any supposed Israeli military elitist cabal or groupthink.

A last memory. In October 2004, when Sharon was trying—yes, Sharon—to get political support for his decision to pull out of Gaza, he sent then defense minister and former military chief of staff Shaul Mofaz to meet with the religious sage of the Shas Party, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef, the former chief Sephardic rabbi of Israel. Rabbi Yosef is a kind of ayatollah-like supreme leader for the Shas Party, and his word is law.

So Mofaz spent much time with him, showing him maps of Gaza and humbly explaining the need to withdraw Israeli settlers there. I remember most vividly the rabbi’s long white beard spread out over a map of Gaza, covering settlers and Palestinians alike with a wiry white fuzz, as Mofaz explained.

The rabbi condemned the withdrawal because it was done without concessions from the Palestinians. But the elected leader of Israel, the scion of the military elite, nonetheless carried out his plans, the first withdrawal of Israeli settlers from occupied land since Yamit.

Steven Erlanger writes on foreign affairs and has been the Paris bureau chief for the New York Times since 2008. He was bureau chief in Jerusalem from 2004 to 2008.

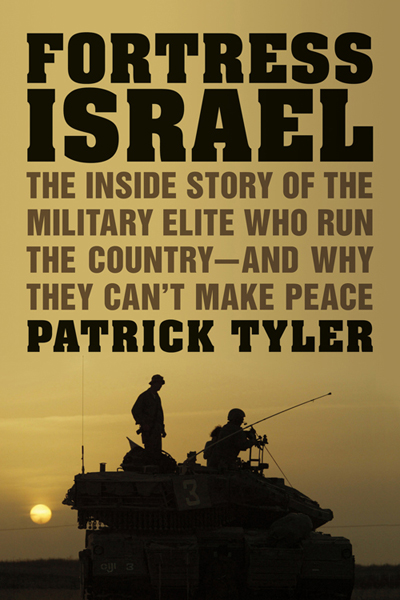

Pullquote: Tyler's book is less an investigation into “fortress Israel” and its supposed ruling military elite than a diligent and insightful history of Israel’s leaders and their military engagements.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review