The Hagiography of Mr. Holbrooke

Mini Teaser: Richard “The Bulldozer” Holbrooke left a deep mark on U.S. foreign policy. Yet this collection of essays by his friends and admirers, which gushes with praise, leaves out significant elements of the story.

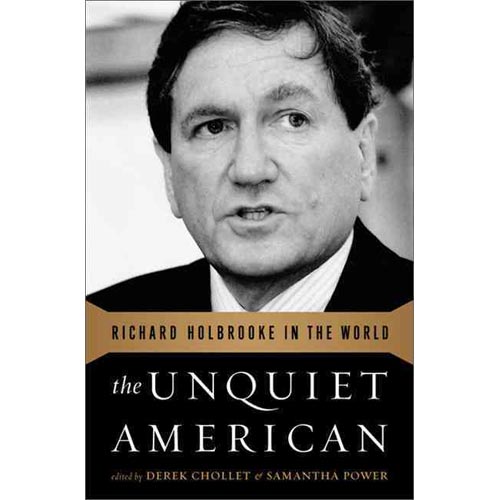

Derek Chollet and Samantha Power, eds., The Unquiet American: Richard Holbrooke in the World (New York: PublicAffairs, 2011), 400 pp., $29.99.

[amazon 1610390784 full]WHEN RICHARD Holbrooke died unexpectedly in December 2010, he left behind a large contingent of friends and admirers who revered the man, his contributions in the realm of foreign policy and his geopolitical outlook. This memorial volume gives testament to that esteem by presenting essays by friends and colleagues as well as Holbrooke’s own writings over the decades. Editors Derek Chollet and Samantha Power succeed in providing a reasonably insightful portrait of Holbrooke the man as well as the foreign policy that he both shaped and embodied.

But a corrective is in order. Holbrooke’s actions and philosophy were problematic in many ways. It does no great service to Holbrooke, and certainly not to his country, to modulate or ignore the controversy generated by his particular geopolitical views—or, for that matter, by the brash, impatient and often bullying demeanor he projected in the course of his official duties. Whatever one thinks of his philosophy or his personal style, it can’t be denied that Holbrooke was a powerful figure who left a large mark, for good and ill, on American foreign policy.

In providing a window into Holbrooke’s foreign-policy views and objectives, The Unquiet American also sheds light on the foreign policy of the Democratic Party’s liberal establishment. Holbrooke was in many respects a poster boy for that faction of America’s foreign-policy elite. His career highlights both the strengths and weaknesses, mostly the latter, of that elevated element of officialdom. Gordon M. Goldstein observes in his contribution to the book that the younger generation of policy makers and scholars emerging from the Vietnam War (the group that the late New York Times columnist William Safire aptly dubbed “the new-boy network”) “remained central to Holbrooke’s life in the decades that followed. And to a remarkable degree, Holbrooke’s circle of intimate colleagues from that chapter would go on to shape the U.S. foreign policy establishment in the post-Vietnam era.”

The role of Holbrooke and other liberal foreign-policy figures is not just a matter of academic or historical interest. Obama administration officials obtain their views from that same intellectual wellspring and embody similar values and prejudices. Thus, the worldview of the Democratic establishment is likely to guide Washington’s foreign policy as long as the current administration remains in power—and in any other Democratic administration in the foreseeable future. One can almost sense Holbrooke’s ghost hovering. And it is a ghost with some hard and sharp edges.

Several essays in this book confirm what many people in Washington already knew: Richard Holbrooke was not an easy man to like. Although Strobe Talbott argues in his contribution that Holbrooke did not fit the stereotype of either the “Quiet American” or the “Ugly American,” he was closer to the latter than the former. One of his nicknames, “The Bulldozer,” captured his utter lack of subtlety and finesse. This bulldozer approach proved particularly damaging when he served President Obama as special envoy to Afghanistan and Pakistan. He alienated rather than intimidated the prickly government and tribal leaders in those countries.

A Holbrooke trait described by Power illustrates his rampantly egotistical persona. “Richard Holbrooke could be crushingly blunt,” she writes:

When he came over for dinner, he would take up the whole meal venting about the inanities of the bureaucracy he served, but then yawn ostentatiously when it took his dinner companions longer than a couple of sentences to get to the point.

Yet he did possess some redeeming qualities. During one of the periods when his Democratic Party was out of power and he did not hold appointive office, Holbrooke worked tirelessly to focus greater attention on the aids epidemic in Africa, even though he received little notice or credit for his efforts. The same was true of his actions to secure the release of journalist David Rohde and others who found themselves held hostage in perilous situations.

A unique feature of Holbrooke’s career is that he served both as assistant secretary of state for East Asia (in the Carter administration) and for Europe (in the Clinton administration). His early career prepared him far more for the former post than the latter. His initial assignment was as a young Foreign Service officer in South Vietnam, where he loyally attempted to execute Washington’s counterinsurgency and nation-building strategy. That experience sobered Holbrooke to some extent, and as the chapter that he wrote for the Pentagon Papers revealed, he had concluded by the late 1960s that the war in Vietnam was unwinnable. Goldstein’s chapter on that phase of his life is one of the stronger contributions to The Unquiet American.

But, typically, even the valid lessons that Holbrooke learned from Vietnam tended to be limited. To the end of his days, he remained committed to the concept of nation building, as evidenced by his April 2002 article in the Washington Post, “Rebuilding Nations.” His criticism of the Vietnam venture was not that the policy of U.S. paternalistic meddling and imperial social engineering was fatally flawed but only that a better strategy—and especially better execution—was needed. His enthusiasm for the nation-building crusades in Bosnia, Kosovo and Afghanistan demonstrated all too well the narrow extent of the lessons he took away from the Vietnam debacle.

The wisdom of Holbrooke’s views and prescriptions regarding other elements of U.S. policy in East Asia was decidedly uneven. He admired the Nixon-Kissinger decision to unfreeze relations with China. Later, as assistant secretary of state, he helped guide the Carter administration through its policy shift of transferring U.S. diplomatic recognition from Taipei to Beijing—in the face of perilous congressional hostility and vigorous opposition from Taiwan.

There were also early hints of new, refreshing thinking about U.S. relations with South Korea and especially the U.S. military presence in that country. While he was out of office during the Ford years, Holbrooke advocated the withdrawal of all U.S. troops from South Korea. As a Carter administration official, though, he reversed course and joined the contingent of diplomatic and military personnel who feverishly lobbied President Carter to abandon his plans to do just that. Unfortunately, Richard Bernstein’s otherwise solid chapter gives little insight into why Holbrooke’s views changed so dramatically.

One explanation is that he changed his mind after studying the issue in greater depth and honestly concluded that a troop withdrawal would pose serious, unanticipated dangers to important American interests. Or perhaps some sentiments of opportunism emerged when he discovered the extent of opposition to the shift from both the military leadership and senior Democrats. Holbrooke’s admirers readily concede his unwavering ambition was to become secretary of state in some future Democratic administration.

But whatever the underlying sentiments, Holbrooke’s ultimate position on the troop presence in South Korea and overall U.S. security policy in East Asia exemplified the myopic, conventional wisdom of the Democratic Party’s foreign-policy establishment—and, indeed, the bipartisan foreign-policy consensus. It was revealing that Holbrooke admired South Korean president Park Chung-hee’s success in persuading Carter that it would be dangerous not only for South Korea but also for Washington’s position and reputation in East Asia and the western Pacific if the proposed troop withdrawal proceeded.

One wonders what Holbrooke and other foreign-policy activists expected Park to say. Two iconoclastic experts on Korean issues—Edward Olsen, a professor emeritus at the Naval Postgraduate School, and Doug Bandow, a former assistant to President Reagan—pointed out that the U.S. military presence confirmed Washington’s willingness to continue providing a major component of South Korea’s defense. That constituted a multibillion-dollar annual subsidy that enabled Seoul to spend far less on its military than prudent national-security considerations regarding the North Korean threat would dictate if South Korea had to take care of its own defense needs. Such cynical free riding was still apparent in the late 1980s when Bandow attended a conference in Seoul and suggested that the time was overdue for South Korea to phase out its military dependence on the United States. A leading South Korean participant sputtered that the government didn’t want to do that because “we have domestic needs.” Park Chung-hee and his successors were not about to give up that robust U.S. defense subsidy, and their American enablers have allowed the free riding to continue to the present day.

The unwillingness (or inability) of the dominant faction in America’s foreign-policy community to envision a more limited, prudent and sustainable role for the United States in East Asia is also evident in its relations with Japan. Holbrooke described the U.S. role since 1945 as “demicolonial,” protecting the noncommunist states in the region from aggression and creating a framework that enabled those countries to pursue economic growth and political stability. To his credit, during his stint as assistant secretary of state in the late 1970s, he recognized that the traditional pattern of the demicolonial policy was already coming to an end.

But, once again, the limits to his analysis were on display. Yes, he (and some other officials) wanted Japan to play a slightly larger political and even military role, but it was always merely as Washington’s strictly controlled junior partner. Holbrooke regarded the notion of Tokyo playing a significantly more robust, much less an independent, role as dangerous radicalism that would threaten to destabilize the entire region. Such crabbed thinking three decades after World War II was already obsolete. Worse still, this thinking would persist far beyond the 1970s. The Pentagon’s 1995 and 1998 planning-guidance documents for East Asia still epitomized a barely concealed worry about a revival of Japanese militarism and saw the United States as the only power that could or should protect the peace and stability of the region.

Pullquote: Whatever one thinks of his philosophy or his personal style, it can’t be denied that Holbrooke was a powerful figure who left a large mark, for good and ill, on American foreign policy.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review