The Hagiography of Mr. Holbrooke

Mini Teaser: Richard “The Bulldozer” Holbrooke left a deep mark on U.S. foreign policy. Yet this collection of essays by his friends and admirers, which gushes with praise, leaves out significant elements of the story.

Distancing himself from those who, he believed, held a “romanticized view” of the United Nations, Holbrooke noted in a November 1999 speech at the National Press Club that the United States had “other vital instruments of national power at our disposal.” Such capabilities were “demonstrated quite amply twice in the last four years: in Bosnia, where NATO, led by the United States, bombed and sent in a NATO-led force without UN authority; and in Kosovo, where the bombing again took place without UN authority.” He added tellingly: “I would advocate similar actions again unhesitatingly if it were in the national interest.”

In other words, Holbrooke, like other liberal interventionists such as Madeleine Albright, saw the United Nations—and, for that matter, other multilateral organizations—as an occasionally useful foreign-policy tool, or at least a convenient fig leaf, for Washington’s foreign-policy objectives. But such liberals did not flinch from bypassing such institutions to pursue very broadly defined national interests.

Holbrooke’s general preference for U.S. activism, within or outside a multilateral framework, underscored his reflexive view of the United States as the world’s one indispensible nation. That attitude was evident in his assumption that a significantly stronger and more active Japan should not become the primary force for security and stability in East Asia. He insisted that only America could, or should, play that role—even in the twenty-first century. Holbrooke preferred a similar static paradigm for Europe in the twenty-first century. Embracing the view that the United States was the only country capable of providing the appropriate security framework for the Continent, he revealed an interesting blind spot. “If the United States does not lead, its European allies could falter as they did in the early part of this decade,” Holbrooke wrote in the pages of the New Yorker in 1998. On other occasions, he sneered at Europe’s lack of any credible military capability to back up its diplomatic pretensions.

But as Alan Tonelson, a research fellow at the U.S. Business and Industry Council Educational Foundation, observed more than a decade ago, the lack of European (and East Asian) military capabilities is largely because of the “smothering strategy” that Washington has employed since the end of World War II. Not only did the United States take on a dominant role in the security affairs of both regions, but it also insisted on maintaining that preeminence. U.S. officials made it clear early and often that they did not view favorably independent security initiatives by their allies. Washington’s opposition to a substantially larger Japanese security role has already been noted, but the hostility to the European Union’s periodic flirtation with developing an independent military capacity was equally intense.

The insistence on U.S. primacy creates a massive incentive for European and East Asian allies to take a free ride on America’s defense exertions. As Cato Institute scholar Christopher Preble argues in The Power Problem, that arrangement has been a very good deal for taxpayers in allied countries. But it has produced two pernicious effects. One is that the allied free riding is an extremely bad deal for U.S. taxpayers. On a per capita basis, Americans pay four to five times as much in military spending as citizens in major European and East Asian allied countries. Even worse, the outsized U.S. security role has fostered an unhealthy, dependent mentality on the part of governments and populations in both regions. The European “fecklessness” that Holbrooke and his colleagues lamented regarding the growing turmoil in the Balkans during the 1990s was a direct—indeed, inevitable—consequence of the U.S. smothering strategy.

Incentives matter in foreign policy as much as they do in domestic policy. It was unrealistic for Holbrooke and others to insist that America is the indispensible nation and then complain about the lack of preparation or initiative on the part of the allies. That is the price of U.S. narcissism, and it is a price that grows ever larger as Washington retains all of its Cold War–era security responsibilities while adding new ones around the world. It is also a price that grows ever more burdensome as America’s fiscal and economic woes mount. It is bizarre, for example, that we are now borrowing money from China so that we can continue defending such nations as Japan and South Korea—at least in part against a possible Chinese security threat.

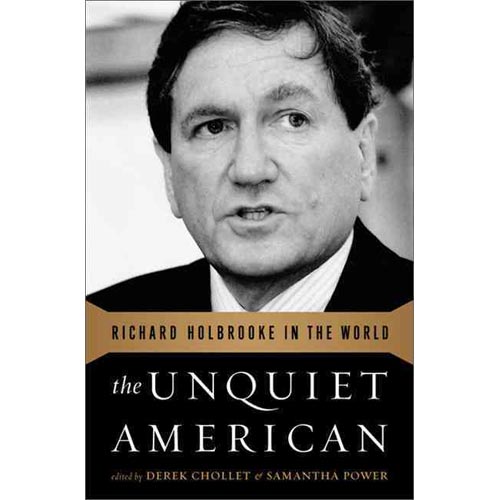

Richard Holbrooke was among a handful of extremely important and influential American foreign-policy figures of the past half century. As The Unquiet American demonstrates, he especially made his mark on policy with respect to East Asia and Europe. But his legacy is a mixed one with more negative than positive features. Ultimately, that disappointing record was due less to his own deficiencies than to the sterile, static worldview that characterizes so much of America’s foreign-policy establishment. The limited nature of the “debate” within that community about America’s appropriate diplomatic and military role in the world has been akin to an excruciatingly boring football game played only between the forty-yard lines.

Bold, new—and badly needed—ideas rarely emanate from the foreign-policy establishment that Richard Holbrooke embodied. The Unquiet American demonstrates that worrisome reality with unintended clarity.

Ted Galen Carpenter, a contributing editor at The National Interest and senior fellow at the Cato Institute, is the author of eight books on international affairs, including Smart Power: Toward a Prudent Foreign Policy for America.

Pullquote: Whatever one thinks of his philosophy or his personal style, it can’t be denied that Holbrooke was a powerful figure who left a large mark, for good and ill, on American foreign policy.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review