The Good Autocrat

Mini Teaser: A stark contrast exists between the tyrannical rulers of the Middle East and the benign despots of East Asia. The precepts of Enlightenment thought dictate freedom for all, but Confucian leaders offer a heretical alternative to Western ideals.

If ever any one, possessed of power, had grounds for thinking himself the best and most enlightened among his contemporaries, it was the Emperor Marcus Aurelius. Absolute monarch of the whole civilized world, he preserved through life not only the most unblemished justice, but what was less to be expected from his Stoical breeding, the tenderest heart. The few failings which are attributed to him, were all on the side of indulgence: while his writings, the highest ethical product of the ancient mind, differ scarcely perceptibly, if they differ at all, from the most characteristic teachings of Christ.

And yet, as Mill laments, this “unfettered intellect,” this exemplar of humanism by second-century-AD standards, persecuted Christians. As deplorable a state as society was in at the time (wars, internal revolts, cruelty in all its manifestations), Marcus Aurelius assumed that what held it together and kept it from getting worse was the acceptance of the existing divinities, which the adherents of Christianity threatened to dissolve. He simply could not foresee a world knit together by new and better ties. “No Christian,” Mill writes, “more firmly believes that Atheism is false, and tends to the dissolution of society, than Marcus Aurelius believed the same things of Christianity.”

If even such a ruler as Marcus Aurelius could be so monumentally wrong, then no dictator, it would seem, no matter how benevolent, could ever ultimately be trusted in his judgment. It follows, therefore, that the persecution of an idea or ideals for the sake of the existing order can rarely be justified, since the existing order is itself suspect. And, pace Mill, if we can never know for certain if authority is in the right, even as anarchy must be averted, the only recourse for society is to be able to choose and regularly replace its forever-imperfect leaders.

But there is a catch. As Mill admits earlier in his essay,

Liberty, as a principle, has no application to any state of things anterior to the time when mankind have become capable of being improved by free and equal discussion. Until then, there is nothing . . . but implicit obedience to an Akbar or a Charlemagne, if they are so fortunate as to find one.

Indeed, Mill knows that authority has first to be created before we can go about limiting it. For without authority, however dictatorial, there is a fearful void, as we all know too well from Iraq in 2006 and 2007. In fact, no greater proponent of individual liberty than Isaiah Berlin himself observes in his introduction to Four Essays on Liberty that, “Men who live in conditions where there is not sufficient food, warmth, shelter, and the minimum degree of security can scarcely be expected to concern themselves with freedom of contract or of the press.” In “Two Concepts of Liberty,” Berlin allows that “First things come first: there are situations . . . in which boots are superior to the works of Shakespeare, individual freedom is not everyone’s primary need.” Further complicating matters, Berlin notes that “there is no necessary connection between individual liberty and democratic rule.” There might be a despot “who leaves his subjects a wide area of liberty” but cares “little for order, or virtue, or knowledge.” Clearly, just as there are good and bad popularly elected leaders, there are good and bad autocrats.

THE SIGNAL fact of the Arab world at the beginning of this year of democratic revolution was that, for the most part, it encompassed few of these subtleties and apparent contradictions. Middle Eastern societies had long since moved beyond basic needs of food and security to the point where individual freedom could easily be contemplated. After all, over the past half century, Arabs from the Maghreb to the Persian Gulf experienced epochal social, economic, technological and demographic transformation: it was only the politics that lagged behind. And while good autocrats there were, the reigning model was sterile and decadent national-security regimes, deeply corrupt and with sultanic tendencies. These leaders sought to perpetuate their rule through offspring: sons who had not risen through the military or other bureaucracies, and thus had no legitimacy. Marcus Aurelius was one thing; Tunisia’s Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, Egypt’s Hosni Mubarak and Syria’s Bashar al-Assad, quite another. Certainly, the Arab Spring has proved much: that there is no otherness to Arab civilization, that Arabs yearn for universal values just as members of other societies do. But as to difficult questions regarding the evolution of political order and democracy, it has in actuality proved very little. To wit, no good autocrats were overthrown. The regimes that have fallen so far had few saving graces in any larger moral or philosophical sense, and the wonder is how they lasted as long as they did, even as their tumultuous demise was sudden and unexpected.

Yet, the issues about which Mill and Berlin cared so passionately must still be addressed. For in some places in the Arab world, and particularly in Asia, there have been autocrats who can, in fact, be spoken of in the same breath as Marcus Aurelius. So at what point is it right or practical to oust these rulers? It is quite possible to force through political change, which leads, contrary to aims, into a more deeply oppressive, militarized or, perhaps worse, anarchic environment. Indeed, as Berlin intimates, what follows dictatorial rule will not inevitably further the cause of individual liberty and well-being. Absent relentless, large-scale human-rights violations, soft landings for nondemocratic regimes are always preferable to hard ones, even if the process takes some time. A moral argument can be made that monsters like Muammar el-Qaddafi in Libya and Kim Jong-il in North Korea should be overthrown any way they can, as fast as we can, regardless of the risk of short-term chaos. But that reasoning quickly loses its appeal when one is dealing with dictators who are less noxious. And even when they are not less noxious, as in the case of Iraq’s Saddam Hussein, the moral argument for their removal is still fraught with difficulty since the worse the autocrat, the worse the chaos left in his wake. That is because a bad dictator eviscerates intermediary institutions between the regime at the top and the extended family or tribe at the bottom—professional associations, community organizations, political groups and so on—the very stuff of civil society. The good dictator, by fostering economic growth, among other things, makes society more complex, leading to more civic groupings and to political divisions based on economic interest that are by definition more benign than tribal, ethnic or sectarian divides. A good dictator can be defined as one who makes his own removal less rife with risk.

While the logical conclusion of Mill’s essay is to deny the moral right of dictatorship, his admission of the need for obedience to an Akbar or a Charlemagne at primitive levels of social development leaves one facing the larger question: Is transition from autocracy to democracy always virtuous? For there is a vast difference between the rule of even a wise and enlightened individual like the late-sixteenth-century Mogul Akbar the Great and a society so free that coercion of the individual by the state only ever occurs to prevent the harm of others. It is such a great disparity that Mill’s proposition that persecution to preserve the existing order can never be justified remains theoretical and may never be achieved; even democratic governments must coerce their citizens for a variety of reasons. Nevertheless, the ruler who moves society to a more advanced stage of development is not only good but also perhaps the most necessary of historical actors—to the extent that history is determined by freewilled individuals as well as by larger geographical and economic forces. And the good autocrat, I submit, is not a contradiction in terms; rather, he stands at the center of the political questions that continuously morphing political societies face.

GOOD AUTOCRATS there are. For example, in the Middle East, monarchy has found a way over the decades and centuries to engender a political legitimacy of its own, allowing leaders like King Mohammed VI in Morocco, King Abdullah in Jordan and Sultan Qaboos bin Said in Oman to grant their subjects a wide berth of individual liberties without fear of being overthrown. Not only is relative freedom allowed, but extremist politics and ideologies are unnecessary in these countries.

It is only in modernizing dictatorships like Syria and Libya—which in historical and geographical terms are artificial constructions and whose rulers are inherently illegitimate—where brute force and radicalism are required to hold the state together. To be sure, Egypt’s Mubarak and Tunisia’s Ben Ali neither ran police states on the terrifying scale of Libya’s Qaddafi and Syria’s Assad nor stifled economic progress with such alacrity. But while Mubarak and Ben Ali left their countries in conditions suitable for the emergence of stable democracy, there is little virtue that can be attached to their rule. The economic liberalizations of recent years were haphazard rather than well planned. Their countries’ functioning institutions exist for reasons that go back centuries: Egypt and Tunisia have been states in one form or another since antiquity. Moreover, the now-fallen dictators promoted a venal system of corruption built on personal access to their own ruling circles. And Mubarak, rather than move society forward by dispensing with a pseudomonarchical state, sought to move it backward by installing his son in power. Mubarak and Ben Ali were dull men, enabled by goons in the security services. The real story in the Middle East these past few months, beyond the toppling of these decrepit regimes, is the possible emergence of authentic constitutional monarchies in places like Morocco and Oman.

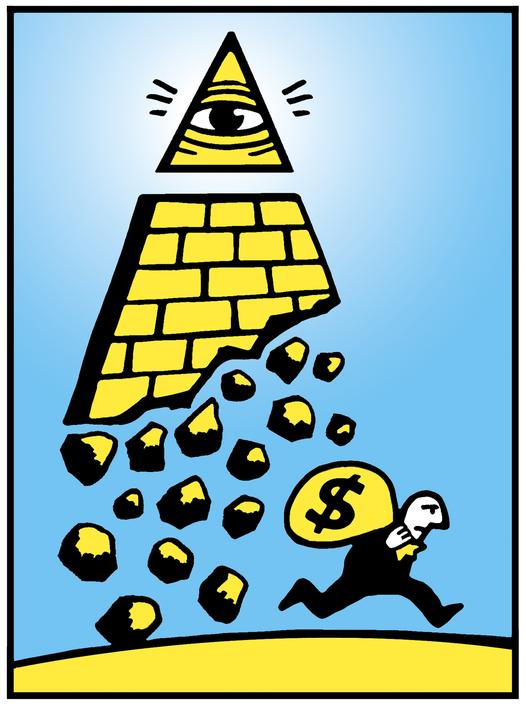

Image: Pullquote: As Isaiah Berlin intimates, what follows dictatorial rule will not inevitably further the cause of individual liberty and well-being.

Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: As Isaiah Berlin intimates, what follows dictatorial rule will not inevitably further the cause of individual liberty and well-being.

Essay Types: Essay