The Many Faces of Neo-Marxism

Mini Teaser: The German thinker's name has been attached to a wide range of modern ideas—poststructuralism, postmodernism, gender studies, etc.—yet he was more a man of his day than of ours.

WE ARE told these days that Karl Marx—one of the most influential thinkers of the nineteenth century, if not the single most important one—is enjoying a kind of renaissance. This is attributed by some to the great economic crisis that began in 2008 and destroyed considerable wealth around the world. Given that this crisis is seen widely as a crisis of capitalism, it is natural that many people would think of Marx, who was of course the greatest critic of capitalism in history.

WE ARE told these days that Karl Marx—one of the most influential thinkers of the nineteenth century, if not the single most important one—is enjoying a kind of renaissance. This is attributed by some to the great economic crisis that began in 2008 and destroyed considerable wealth around the world. Given that this crisis is seen widely as a crisis of capitalism, it is natural that many people would think of Marx, who was of course the greatest critic of capitalism in history.

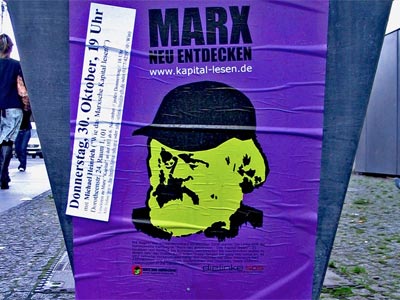

Yet it is a strange renaissance, if indeed it is any kind of renaissance at all. In recent years, there have been many Marxism conferences and countless workshops in places such as Chicago, Boston and Berlin. In London, one Marx “festival” lasted five days under a slogan that cried, “Revolution is in the air.” The invitation read:

Crisis and austerity have exposed the insanity of our global system. Billions have been given to the banks, while billions across the planet face hunger, poverty, climate catastrophes and war. We used to be told capitalism meant prosperity and democracy. Not any more. Now it means austerity for the 99% and rule by the markets.

But is revolution really in the air? France got a socialist government, but it is already in trouble. Britain may follow, but would it fare any better? It seems only natural that, at a time of crisis, public opinion would turn against the party in power. Given the severity of the crisis and the slowness of the recovery, it is not surprising that some people would turn to Marxism. But the fact that the political reaction has been so mild is more astonishing.

And, while some of the conferences and festivals lauding the anticapitalist crusader seem to be motivated by genuine neo-Marxist sentiments, others appear to be using the man as a kind of bandwagon for separate trendy causes and impulses. Consider the agenda at a recent such meeting at the University of Washington. One has to doubt whether these followers of Marx are on the right track when the papers under discussion contain titles such as “Reconsidering Impossible Totalities: Marxist Deployments of the Sublime,” “A Few Thoughts on the Academic Poet as Hobo-Tourist,” “Reading Hip-Hop at the Intersection of Culture and Capitalism,” “Annals of Sexual States” and “The Political Economy of Stranger Intimacy.”

One wonders what Marx’s reaction would be if he sat at his desk in the British Museum’s Reading Room and contemplated such discussions at a gathering dedicated to rethinking his ideas. Would he be impressed, amused or speechless? Perhaps it would remind him of the carnival celebrations each February in his native Trier: wine, funny masks and customs, and pranks—all followed by a hangover of five or six days.

THESE MUSINGS are stirred by the arrival of the latest major Marx biography—Karl Marx: A Nineteenth-Century Life,by Jonathan Sperber (W. W. Norton, 672 pp., $35.00). Sperber is an expert on nineteenth-century Germany, and there is much in his book about Marx’s adolescence there, especially in his native Trier. Sperber also deals with Marx’s political activism and his relations with other German revolutionaries in exile in greater detail than previous biographers. Sperber applauds a new interpretation of Marx that looks at the man in the context of his own nineteenth century rather than as a harbinger or instigator of twentieth-century conflict.

“The view of Marx as a contemporary whose ideas are shaping the modern world has run its course,” he writes, “and it is time for a new understanding of him as a figure of a past historical epoch, one increasingly distant from our own.” Among elements of that past historical epoch, he cites the French Revolution, G. W. F. Hegel’s philosophy, and the early years of English industrialization and the political economy stemming from it. “It might even be,” he adds, “that Marx is more usefully understood as a backward-looking figure, who took the circumstances of the first half of the nineteenth century and projected them into the future, than as a surefooted and foresighted interpreter of historical trends.”

Thus, rather than seeking to illuminate the intellectual clashes of the modern era by bringing Marx into our own time, Sperber attempts to illuminate Marx’s time by transporting his readers back there.

This is not, strictly speaking, a book review but rather an exploration of how history has viewed Karl Marx through various epochs and vogues of thought since he dropped his momentous theories into the Western consciousness a century and a half ago. What can be said about Sperber’s effort, though, is that he tells his story well and should be commended for his competence and reliability. Besides, the publication of a new Marx biography should be welcomed. If people today lack the time or inclination to read Marx—and he isn’t read much these days—one should at least read about him.

One manifestation of the Marx renaissance is that Sperber is not alone. A number of biographies of the man have been published in recent years; one can think of four in English alone. In the decades after World War II, interest in Marx was limited even though Communist and Social Democratic parties were strong at the time. But the basic facts about Marx’s life were pretty well known: his years as a student, his involvement with the young Hegelians, his activity as a left-wing democrat and his discovery of socialism, the years in Paris and Brussels, and eventually his life in London studying capitalism, pondering the class struggle and historical materialism. Information and documents, however marginal, that shed light on Marx’s life were collected in major institutes in Moscow, Amsterdam and London. The Marx-Engels-Lenin Institute in Moscow was the largest and best equipped of these, but it was closed in 1993. The Amsterdam International Institute of Social History, founded in 1935, still exists, as does the Marx Memorial Library located in Clerkenwell Green in London’s East End.

For many years, Franz Mehring’s Karl Marx: The Story of His Life—first published in 1918, and still in print today—was the leading text in the field. Mehring was a “bourgeois” journalist who found his way at midlife to the socialist movement. It is a decent work, very respectful of the master but not entirely uncritical. Orthodox Marxists never forgave Mehring for defending Ferdinand Lassalle and Mikhail Bakunin against often-intemperate attacks by Marx. Lassalle, of German Jewish origin, was the founder of the first German socialist party. He was a very talented and charismatic leader but highly unstable—occasionally given to harebrained schemes and actions. As a theoretician he was not remotely in Marx’s league, but he resided in Germany and was therefore more popular and better known among workers than the distant Marx. Lassalle died young in a duel concerning the good name of a young lady of aristocratic origin. Marx, who had been in close contact with him, later referred to him as that “Jewish nigger,” among other ungracious epithets.

Author of an excellent biography of the Marx family, Mary Gabriel decided not to reveal to her readers such Marx malefaction on the grounds that it might create a mistaken impression. Of course, such language was all too common at the time and should not be measured against today’s higher standards of discourse. Marx, to borrow a phrase coined by Freud, was “badly baptized.” Instead of dissociating himself quietly and more or less elegantly from his tribe, he seemed bothered and self-conscious about his Jewish heritage. But Lassalle wasn’t exactly a proud Jew either; in a letter to his fiancé he wrote that he hated the Jews. But in the end, Gabriel’s sanitation seems misplaced; judgment should be left to readers.

As for the famous Russian anarchist, Bakunin, he too had once been close to Marx but later fell out with him. There developed between them genuine political differences after Bakunin embraced anarchism, but Marx’s deep and unshakable Russophobia played a part as well. Marx was a great believer in conspiracy theories; for many years he insisted that Lord Palmerston, the British prime minister, was a secret Russian agent. On the other hand, Marx trusted the spies that Prussian and German governments had planted in his inner circle. He was not much of a judge of his fellow human beings.

THE MEHRING biography is no longer adequate for our time. It was bound to be incomplete because Marx’s early writings and much of his correspondence became accessible to a wider public only in 1932. Nor was it known outside a very small circle that Marx had fathered a boy with Helene Demuth, the faithful domestic in the Marx London household. Marx’s illegitimate son was the only member of the family to live and witness the victory of socialism (as it was then called) in Russia.

Among other biographies, there is general agreement that David McLellan’s Karl Marx: His Life and Thought is the standard work. It was written in the 1970s, before the breakdown of the Soviet Union, and is now in its fourth edition. But other books have stressed distinctive aspects of Marx’s life and merit attention for that. Francis Wheen’s book, Karl Marx: A Life,is well written and was well received for its emphasis on Marx’s English contemporaries. Wheen deals with Marx’s exchanges with Darwin in greater detail than other authors. Although Wheen takes issue with other biographers, the bones of contention are not fundamental.

Gabriel’s 2011 book, Love and Capital: Karl and Jenny Marx and the Birth of a Revolution, is also well researched, though more preoccupied with love than capital. She deals primarily with Marx’s wife but also with his children, four of whom died before he did. Marx’s relations with his children seem to have been very good, and his daughters adored him. His wife, born into the aristocratic German von Westphalen family, had an unenviable fate. For most of her marriage, she lived in dire poverty, and her aristocratic background and upbringing had not prepared her for a life in such miserable conditions. Marx himself wrote on more than one occasion that he often felt reluctant to go home to her because of the constant whining and complaining. The only earlier serious and sympathetic study of her life was written by her nephew once removed, the Prussian nobleman Lutz Graf Schwerin von Krosigk, who served as Hitler’s finance minister (though he was not a member of the Nazi Party) and served time in Spandau prison after the war.

Thus, there is no lack of serious and reliable Marx biographies, including relatively recent ones. Sperber’s entry is a worthy addition to the collection. He is to be commended particularly for his warning against the faddish tendency of modern scholars to make Marx’s ideas more relevant to the present by putting them through a Cuisinart along with various bromides of our time such as structuralism, postmodernism, existentialism and the like.

But Sperber’s nineteenth-century focus raises some interesting questions of its own. Marx’s historical importance, it could be argued, is mainly as the man who gave Lenin his ideas, not the polemicist who wrote a book attacking the theories of, for example, Carl Vogt, whose views are almost entirely in eclipse today. Sperber certainly is justified in dismissing various attempts to update Marx, which have ranged from the ridiculous to the absurd. At the same time, he may go too far in dismissing as useless the preoccupation with Marxism, which he calls “Marxology.” After all, Marx’s private life and his interventions in the politics of his time, interesting as they are, aren’t why he is remembered today.

He is remembered—for better or worse—as the man who provided an outline, even if somewhat vague, for a postcapitalist world. Thus, the author of the draft of the future society is remembered primarily by those who lived to witness it. That is probably why Moscow authorities have seriously considered removing from the capital the last remaining statue of Marx (it stands opposite the Bolshoi Theatre). Interest in Marx and Marxism seems to be least robust today in the very countries in which his teachings were once invoked and where schoolchildren were instructed to study him.

But is it fair to blame philosophers for any and every mutilation of their ideas—the concept that a tree is known by its fruits? Francis Wheen, for one, argues that it is not. And it would indeed be wrong to blame Marx for Stalin or Pol Pot, just as Nietzsche cannot be made responsible for Hitler or Eichmann. Still, a lot of civic activity unfolded in the twentieth century in Marx’s name, much of it tragic. And his attack on capitalism, so powerful and sweeping, was destined to find resonance through the decades whenever the faults and limitations of capitalism became most visible and pronounced.

WHICH BRINGS us back to the so-called Marx renaissance and how it happened that he should be enjoying renewed interest, however muted, after so much controversy over so long a time. Some knowledge of Marx’s writing was taken for granted in my generation, between the two world wars. This was not true with regard to the generation of the parents and certainly not the grandparents. But when I was growing up a third of the world was ruled under systems that were, or claimed to be, guided by Marxism. How could people in such a time make sense of current events unless one knew something about the ideology that was the lodestar of these countries?

It should probably be revealed that this knowledge did not extend to Marx’s great opus, Das Kapital. Outside a small circle of specialists, I knew no one who had ever read it to the end. But it was the norm to at least pretend that one had started reading it.

And it is worth noting some anecdotal evidence of Marx’s place in the consciousness of people back then. My little apartment in London is almost literally a stone’s throw from Marx’s grave in Highgate. In days of old, on an afternoon stroll, rain or shine, I was asked at least once for directions to the grave by visitors, often from abroad—students from Germany, middle-aged Americans, on one occasion monks from some Far Eastern country. During the last two decades the stream of those wishing to pay homage to the man has dwindled almost to the vanishing point. There was no great outcry when the gravesite visiting hours were cut.

As for the circulation of Marx’s works, a cursory inquiry shows that there has been a rise of late, with 1,500 copies of Das Kapital sold by one publisher in Germany in 2008, up from the roughly two hundred it previously sold annually. There has also been an increase in China, where in 2009 one of the country’s principal publishing houses reported a fourfold rise in the book’s sales following the onset of the financial crisis. But it isn’t much of an uptick. Marx’s works don’t sell more notably than other political-theory classics—less than Milton Friedman’s Capitalism and Freedom, and far less than certain cult books such as those by Ayn Rand. But Marx’s Communist Manifesto, a long essay of sixty to eighty pages, does seem to sell well.

The Marx renaissance seems concentrated mostly on the United States and Germany. The German city Chemnitz, renamed Karl-Marx-Stadt after the Communist takeover of East Germany in 1945, has regained its old name. But a local savings bank there has issued a credit card called the “Marx card,” complete with a rendering of the man, and it proved to be a successful publicity stunt. Leading German movie producer Alex Kluge has made a ten-hour “poetic documentary” (his words) on Das Kapital. The idea was not entirely original to him. The great Soviet movie director Sergei Eisenstein contemplated a similar project decades ago and even tried to persuade James Joyce to collaborate with him on it. Nothing came of it.

But Kluge’s extended work, available on DVD, takes Eisenstein’s concept as a starting point and goes from there. He titled his film News from Ideological Antiquity. And it must be noted that the work serves to justify Sperber’s misgivings about trying to make Marx “more relevant to our time” by reinterpreting him in the light of structuralism, poststructuralism, postmodernism, existentialism or elements of so many other movements that have littered the modern intellectual landscape over the past century or so. Attempts have been made, for example, to meld Marxism with postcolonial criticisms of Western imperialism, but this is a difficult argument to make in light of Marx’s observation that Britain played a progressive role in the development of India.

One sees similar disconnected analysis elsewhere in the Marx renaissance. Terry Eagleton—who wrote Why Marx Was Right and is a leading figure in the revival—is a staunch fighter against Islamophobia and a well-known theoretician in the field of literary theory. Others involved in the revival are students of religion, philosophy, psychoanalysis, postcolonialism, commensality (eating together), identity politics, gender politics, the environment and so on. All may be important subjects, but they are not ones that were particularly close to Marx’s heart and mind.

Some examples of people from various specialties who have jumped on the Marx bandwagon: Etienne Balibar, who wrote on Baruch Spinoza; Alain Badiou, whose specialty is truth and logic; Slavoj Zizek, a scholar of psychoanalysis, film theory and many other subjects; and Jacques Ranciere, a philosopher of education. A distinguished professor of geography and anthropology at the City University of New York, David Harvey, offers a course dedicated to a close reading of Das Kapital.

MISSING FROM this parade of people attempting to bring Marx up to date in our time are professors and scholars whose expertise centers on economics and finance—the subjects to which Marx devoted most of his life and which are at the center of the present global crisis. Historians such as Sperber also are rare in this pantheon. Of course, no one would argue that only economists and actual scholars of Marxism should participate in these debates, but their almost-total absence makes one wonder what this debate is all about.

It is difficult to discern, for example, what creative impulses Marx may have contributed to “Marxist Feminist Notes on the Political Valence of Affect,” the title of a paper given by Rosemary Hennessy of Rice University at the Berlin Marxism conference.

All of which raises a question: If this perceived Marx renaissance has little to do with the actual teachings of Marx, with which the poststructuralists, postmodernists and gender scholars seem only vaguely familiar, how does one explain the renaissance, however modest it may be and however restricted to elite Western universities that have little connection to today’s industrial working class?

The answer, it seems, is that “Marx” has become something like a shortcut or a symbol indicating a predilection for radical change in a wide variety of fields loosely called “cultural studies.” It has little or nothing to do with what Marxism was really all about.

An exploration of this modern phenomenon of Marxism requires that we go back in time. Marx was a genius, but he was not the most reliable of prophets. He provided insights of great importance to the study of economics and of society. Without historical materialism, the importance of the class struggle in history would not have been understood as clearly as it has been. His impact on twentieth-century politics was enormous. But even before the nineteenth century ended, some people closest to him realized that history was not moving in the direction he predicted.

One of these was Eduard Bernstein, a native of Berlin who lived many years in London. He was a friend of the family and, together with Marx’s daughter Eleanor, edited much of the unpublished correspondence and papers of the master after his death. Writing in 1898, he said his intent was not to refute Marx but simply to bring him up to date in light of events. Bernstein saw clearly that pauperization—the process of increasing misery of the proletariat predicted by Marx—was not taking place. Neither was the concentration of capital in a few hands, which Marx saw as an inevitable cause of the collapse of capitalism. Neither did Marx foresee the emergence of the welfare state.

True, there were recurrent crises of capitalism, but they were not those anticipated by Marx. The workers of the world did not unite. The industrial working class did not grow but shrank. Following technological progress, the composition of the working class changed significantly. In Europe, it encompassed many immigrants for whom religion was more important than class-consciousness. And the native working class frequently gravitated to the right—sometimes even to the far right, as in France.

Revolutions did emerge in some countries, but not in the most developed capitalist countries that Marx saw as the spawning ground for revolution. Rather, they occurred in less developed nations whose new revolutionary societies were quite different from what Marx had imagined.

Thus did Marxism rise not on the scientific character of its teaching but on the utopian and romantic idea of revolution. Marx had been contemptuous of the utopian socialists of his time, and his doctrine contained scientific elements. But these elements soon gave way to the general discontent among intellectuals with the status quo, the wish of many to do away with the system’s social and cultural imperfections, and the yen for new cultural values and norms.

What fresh impetus can reasonably be expected from the contemporary Marx renaissance? Expectations should be modest. Marx’s preoccupation was with the inner contradictions of capitalism and the political future of the industrial working class. The renaissance was triggered by the crisis in the developed countries that began in 2008. Marx focused primarily on Britain but also, to a lesser extent, on other European countries that then represented the capitalist vanguard. Yet any serious analysis of capitalism today would focus less on England and more on China.

Among the topics of interest embraced by those involved in the Marx renaissance, in addition to those noted above, are alienation, reification, and other such literary and philosophical pursuits. But such matters have almost nothing to do with today’s crisis of capitalism in Europe and America. It is a debt crisis, raising powerful questions about whether stimulus or austerity is the best medicine to get the economy balanced and moving again. This crisis has almost nothing to do with, say, Marx vs. Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, the Austrian School economist whose views differed from Marx’s in important ways that now seem trivial. Today the more relevant debate is John Maynard Keynes vs. Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman.

In this situation, it is likely that the regulatory state will play a greater role than in the past. A great deal of ill will has welled up against the financial system in part because of the greed displayed by some of its leading movers and shakers but also because of their devastating incompetence. Still, no one so far—neither individuals nor political parties—has suggested the wholesale nationalization of key branches of the economy, the means of production or the banks. That’s what a Marxist approach would look like.

THE CHALLENGE facing Europe and America now is that a new economic world order is emerging. Europe—no longer the main exploiter—will have to think and work hard to save the welfare state, and America will have to do the same for its entitlements. How can these societies find a niche that will enable them to keep their standards of living, or at least prevent too rapid a decline?

Where will they find guidance on how to meet such challenges? It isn’t likely to be found in the venerable works of the British classical economist David Ricardo or the later British economist Nassau William Senior. And not even geniuses such as Adam Smith or Marx can really lead us much further in the pursuit of such guidance. History has moved on. The nineteenth century and its industrial fervor are far behind us.

Will America lead the way? Will China? Marx wrote in an 1850 article for a German newspaper, “When our European reactionaries in the flight to Asia . . . come at length to the Great Wall of China . . . who knows if they will not find there the inscription: République Chinoise. Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité.” But of course no such inscription is to be found at that wall. At most it symbolizes the observation of the late Giovanni Arrighi, the Italian American economics professor of Marxist persuasion, who once wrote that China had a market economy but not a capitalist one. An interesting point but not particularly helpful in meeting the challenge of the world’s contemporary problems.

And so it appears we shall have to wait a bit longer for some kind of lodestar to emerge. In the meantime, it is clear that the perceived renaissance of Marxism, such as it is (which isn’t much), doesn’t offer anything of value in this search. No doubt it will continue to stir fascination in the breasts of activists in various fields of cultural studies, weary of the status quo and hungry for a revolutionary new ethos. But it has nothing to offer the economists of our day—or the rest of mankind, for that matter.

Walter Laqueur is a historian and political commentator. His most recent book is After the Fall: The End of the European Dream and the Decline of a Continent.

Image: Flickr/Karl-Ludwig G. Poggemann. CC BY 2.0.

Image: Pullquote: 'Marx' has become something like a shortcut or a symbol indicating a predilection for radical change in a wide variety of fields loosely called 'cultural studies.'Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: 'Marx' has become something like a shortcut or a symbol indicating a predilection for radical change in a wide variety of fields loosely called 'cultural studies.'Essay Types: Essay