When Kerry Stormed D.C.

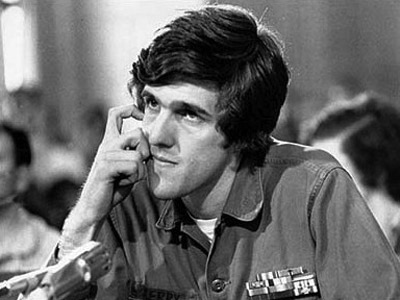

Mini Teaser: John Kerry was just five years out of Yale when he testified before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and became an instant celebrity.

DURING THE Vietnam War, there were many memorable hearings at the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, but none resonated with the raw power and eloquence of John Kerry’s on April 22, 1971. It was a time of crisis in America—a war seemingly without end for a goal still without clarity, in a country split not only on the war but also on a host of emotional political, cultural and social issues.

DURING THE Vietnam War, there were many memorable hearings at the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, but none resonated with the raw power and eloquence of John Kerry’s on April 22, 1971. It was a time of crisis in America—a war seemingly without end for a goal still without clarity, in a country split not only on the war but also on a host of emotional political, cultural and social issues.

When Kerry entered room 4221 of what is now called the Dirksen Senate Office Building, its impressive walls covered with maps and books and with nineteen senators seated behind a huge U-shaped table, he did more than add instant credibility to the dovish cry for Congress finally to do something about ending the war, even going so far as to advocate cutting off funding; he personalized the war that for so many others still seemed a puzzling, costly embarrassment in an unfamiliar corner of the world.

Kerry was a 1966 Yale graduate who had volunteered for duty in Vietnam, where he served honorably, winning two medals for courage and three Purple Hearts. “I believed very strongly in the code of service to one’s country,” he said. By that time, 56,193 Americans had died in and around Vietnam, and campuses were ablaze with antiwar rallies. Many students escaped military service by joining the National Guard or fleeing to Canada.

Dressed in green army fatigues, with four rows of ribbons over his left pocket, the twenty-seven-year-old survivor of dangerous Swift Boat missions leveled a blistering attack on American policy in Vietnam, his New England accent adding a dimension of authenticity to the sharpness of his critique. When he finished his testimony an hour later, he had become, in the words of one supporter, an “instant celebrity . . . with major national recognition.”

Speaking on behalf of more than a hundred veterans jammed into the Senate chamber and more than a thousand others camped outside to demonstrate against the war, Kerry demanded an “immediate withdrawal from South Vietnam.” He came to Congress, and not the president, he said, because “this body can be responsive to the will of the people, and . . . the will of the people says that we should be out of Vietnam now.”

If Kerry had simply expressed this demand, and not amplified it with reports of American atrocities, he likely would have avoided the devastating criticism that hounded him throughout his political career—criticism that eventually morphed into charges of treason and treachery, deception and lies, cowardice and even more lies, undercutting his presidential drive in 2004.

Kerry told the committee that in Detroit a few months earlier, 150 “honorably discharged . . . veterans” launched what they called the “Winter Soldier Investigation.” In 1776, Kerry said, the pamphleteer Thomas Paine had written about the “sunshine patriot,” who deserted his country when the going was rough. Now, Kerry continued, the going was rough again, and the veterans who opposed the war felt that they had to speak out against the “crimes which we are committing.”

Kerry emphasized the word “crimes,” and most of the senators and all of the journalists leaned forward in their seats. A hush fell over the room. I was among the reporters covering Kerry’s testimony. During the 1960s and early 1970s, when, as diplomatic correspondent for CBS News, I reported on a number of important foreign-policy deliberations at the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, I generally stood with my camera crew in the back of the room. Rarely was it crowded. Most of the radio, newspaper and magazine reporters gathered around a large rectangular table near the tall windows. A second large table was on the other side of the room. Between the two and directly behind the witness table were rows of chairs for aides, guests and tourists.

On this very special day, however, the seating rules were suspended. I arrived early, but even so most of the seats were already taken. The veterans squeezed into the back of the room, most standing, very few seated. I spotted one empty chair in the front row and ran for it, beating out a network competitor by half a step. I was lucky; I had a great seat, no more than six feet from where this young antiwar leader was to deliver testimony that yielded the immediate advantage of dominating the news that day. Kerry hoped this would be the case, but it also carried the unintended consequence of providing ammunition to his political opponents to prove he was unworthy of higher office.

KERRY STARTED with his most explosive charge. He quoted the “very highly decorated veterans” who had unburdened themselves in Detroit, saying:

They told the stories at times that they had personally raped, cut off ears, cut off heads, taped wires from portable telephones to human genitals and turned up the power, cut off limbs, blown up bodies, randomly shot at civilians, razed villages in fashion reminiscent of Genghis Khan, shot cattle and dogs for fun, poisoned food stocks, and generally ravaged the countryside of South Vietnam.

Kerry continued, “The country doesn’t know it yet, but it has created a monster, a monster in the form of millions of men who have been taught to deal and to trade in violence.” He was describing his buddies, the Vietnam veterans on the Washington Mall, and many others, the “quadriplegics and amputees” who lay “forgotten in Veterans’ Administration hospitals.” They weren’t “really wanted” in a country of widespread “indifference,” where there were no jobs, where the veterans constituted “the largest corps of unemployed in this country,” and where 57 percent of hospitalized veterans considered suicide.

I suspect most of us in room 4221 were shocked by Kerry’s description of the veterans just back from the Vietnam War. I had always thought of the American soldier as a brave, patriotic and honorable warrior—that had been my personal experience in the U.S. Army—not as a “monster . . . taught to deal and to trade in violence” who “personally raped, cut off ears, cut off heads,” comparable to the rampaging legions of Genghis Khan in the thirteenth century. Kerry’s words evoked images totally foreign to the American experience, certainly to me. I wondered: Could Kerry be right? After all, he had fought in Vietnam. I hadn’t.

We were by then familiar with the so-called credibility gap, the “five o’clock follies” in Saigon, and White House briefings pumped up with artificial optimism and more than an occasional fib. And if Kerry was right, how could the senators have been so wrong, so gullible? How could we Washington journalists, who had covered so many other hearings, speeches and backgrounders, have been so misled? More pointedly, how could we have allowed ourselves to be so misled? Could Kerry’s portrait of the American veteran actually be a portrait of Dorian Gray in khaki?

Listening to this decorated veteran, a Yale graduate with an old-fashioned sense of service and patriotism, I thought of the political scientist Richard Neustadt’s emphasis on the importance of “speaking truth to power.” I had the feeling that this veteran was speaking truth to Congress and to the American people, though with a flair for hyperbole that he was later to regret. Often, during his testimony, I found myself in a state of semi-hypnosis, pen in hand but not taking notes, absorbed by the boldness—and relevance—of his criticism. The massacre at My Lai was in the air. Army lieutenant William L. Calley had been on the cover of Time. If a lieutenant could burn down a village with a Zippo lighter, was it not possible that another lieutenant could be high on drugs—and then rape and kill? Could Kerry be right? I had once been a hawk on the Vietnam War—I had thought that stopping Communism in Southeast Asia was as sound a strategy as stopping it in Europe. But after the Tet Offensive in early 1968, and after General William Westmoreland’s stunning request for an additional 206,000 troops, to be added to the 543,000 troops already in theater (a request fortunately rejected by the new secretary of defense Clark Clifford), I began to change my mind not only about the strategy but also about the very purpose of the war. That day, Kerry pushed me (and many other Americans) over the brink. I began to think that the United States had made a terrible mistake in Southeast Asia and that it was time to admit it and take the appropriate action.

Indeed, every now and then, a question crystallizes a national dilemma. Kerry asked: “How do you ask a man to be the last man to die in Vietnam? How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?” If the war was a mistake, then why pursue it? One reason was that President Richard Nixon did not want to be, as he put it, “the first President to lose a war,” even though he knew that Vietnam was an “unwinnable proposition.” And then Kerry asked another question of equal pertinence: “Where are the leaders of our country?” Much to my surprise, as he listed his candidates for ignominy, he did not include Nixon or Henry Kissinger. “We are here to ask where are McNamara, Rostow, Bundy, Gilpatric,” he continued:

These are commanders who have deserted their troops, and there is no more serious crime in the law of war. The Army says they never leave their wounded. The Marines say they never leave even their dead. These men have left all the casualties and retreated behind a pious shield of public rectitude.

The senators did not move. The reporters tried to look unmoved. The room was very silent. Only the cameras hummed politely as they recorded Kerry’s testimony for later broadcast to the nation.

In conclusion, Kerry accused “this administration” of paying the veterans the “ultimate dishonor.” He said, “They have attempted to disown us and the sacrifice we made for this country. In their blindness and fear they have tried to deny that we are veterans or that we served in Nam. We do not need their testimony. Our own scars and stumps of limbs are witnesses enough for others and for ourselves.”

And then, more in sadness than artificial pomp, though maybe a bit of both, since Kerry was an accomplished orator, he finished with these words:

We wish that a merciful God could wipe away our own memories of that service as easily as this administration has wiped their memories of us. But all that they have done and all that they can do by this denial is to make more clear than ever our own determination to undertake one last mission, to search out and destroy the last vestige of this barbaric war, to pacify our own hearts, to conquer the hate and the fear that have driven this country these last 10 years and more, and so when, in 30 years from now, our brothers go down the street without a leg, without an arm, or a face, and small boys ask why, we will be able to say “Vietnam” and not mean a desert, not a filthy obscene memory but mean instead the place where America finally turned and where soldiers like us helped it in the turning.

The room, which had been still, erupted in applause and cheers. The Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW), the organization Kerry was representing, had finally been heard, not just on Capitol Hill but in time across the nation. Outside, among the veterans gathered on the Washington Mall, small groups formed around transistor radios, listening to Kerry’s critique. Many got down on one knee, raising their right fists to the sky. American flags were unfurled. One could even see a number of Vietcong banners. On the fringes, there were other flags: “Quakers for Peace” and “Hard Hats Against the War.” One veteran, who had lost both legs, sat in a wheelchair—he too raised his fist to the sky. He had fought his last war.

CHAIRMAN J. William Fulbright, a Democrat from Arkansas, who had helped steer the Tonkin Gulf resolution through Congress in August 1964, providing the “legal” authority for American military action in Vietnam, but who later became an active critic of the war, praised Kerry for his eloquence and his message and asked whether he was familiar with the antiwar resolutions then under discussion and debate in Congress. Fulbright said that a number of committee members had advanced resolutions to end the war, “seeking the most practical way that we can find and, I believe, to do it at the earliest opportunity that we can.” Kerry responded that his veterans would like to end the war “immediately and unilaterally.” Based on his talks with the North Vietnamese in Paris, Kerry believed, naively as it turned out, that if the United States “set a date . . . the earliest possible date” for its withdrawal from Vietnam, the North Vietnamese would then release American prisoners of war. What we later learned was that the North Vietnamese had other plans. Kerry added that he didn’t “mean to sound pessimistic,” but he really didn’t think “this Congress” would end the war by legislation.

Senators known for their volubility sat speechless.

“You have a Silver Star; have you not?” injected Senator Stuart Symington of Missouri. A Silver Star was the army’s third-highest award for valor.

“Yes, I do,” Kerry responded.

“You have a Purple Heart?” Symington continued.

“Yes, I do.”

“How many clusters on it?”

“Two clusters.”

“You were wounded three times?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I have no further questions,” Symington concluded.

Other senators asked other questions, but they were mostly in the form of compliments and congratulations—they were not probing for substantive information.

Fulbright and Kerry were obviously reading from the same sheet of antiwar music. The two had met at a reception honoring the VVAW held at the home of Senator Phil Hart of Michigan, and Fulbright liked Kerry’s style. He was, according to historian Douglas Brinkley, “very impressed by Kerry’s polite . . . demeanor. He was not a screamer. He didn’t look disheveled.” The next morning a Fulbright staffer called Kerry. “We want you to testify,” he said. Happily, Kerry agreed, even though he knew he did not have enough time to prepare properly. With Adam Walinsky, a former aide to both John and Robert Kennedy, at his side, Kerry spent the whole night writing and rewriting his testimony, while balancing other responsibilities as one of the principal coordinators of the five-day demonstration.

Around 9:30 a.m., Thursday, April 22, 1971, a friend, reporter Tom Oliphant of the Boston Globe, found Kerry at a meeting at a demonstration on the Hill. “Do you realize what time it is?” he asked. “Shouldn’t we get going?” Kerry checked his watch. “Oh, my God,” he said. “Let’s go.” With Oliphant, he set off at a brisk pace down Independence Avenue toward the Dirksen Senate Office Building. As they passed the Supreme Court, Kerry noticed an angry group of veterans on the top steps of the building. He then did what he had been doing all week. “Up he went, and once again, you know, the hand on the arm, the talking them down.” Oliphant heard Kerry say: “We don’t want any sideshows. Please help.” Kerry always worried about image—about whether the veterans, many of them looking like Woodstock hippies, were making a positive impression on the American people.

By then, it was “six or seven minutes” to the start of the hearing. “Uh, John,” Oliphant said, pulling on his sleeve, “you might want to go testify before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.” Kerry broke away from the protesting veterans. The two rushed off to room 4221. “We got to the door, and I actually opened it,” Oliphant remembered, “and he started to go towards it, at which point he pulled back like somebody had punched him, just went back like this, and said, ‘Oh shit!’” Kerry had just caught his first glimpse of the crowded, noisy conference room. He suddenly realized he was entering the big leagues of national politics.

Oliphant continued:

The room was completely jammed. There was a full spread of television cameras, completely filled press tables, the most prestigious committee in the entire United States Congress, to see a twenty-seven-year-old in combat fatigues make a statement about the Vietnam War. The response, not just inside the hearing room, but nationally—it was electric, and it was immediate. This person and that message had gone national in the blink of an eye.

AT THE White House, which had anxiously observed the antiwar demonstration all week and done everything in its power to contain and downplay it, President Nixon met with his chief of staff, H. R. Haldeman, to consider other steps they could take against the antiwar veterans. Neither could ignore the impact of Kerry’s testimony. They had decided early on that the Nixon administration would have no contact with these veterans. No official would be allowed to talk to them or to receive them at the White House, the Pentagon or the State Department. They had even refused to grant permission to five “Gold Star Mothers” to enter Arlington National Cemetery to lay two wreaths at gravesites for Asian and American soldiers. The next morning, seeing the negative play in the media, they changed their minds and allowed a few of the “Mothers” to enter. The administration also withheld permission for the veterans to camp on the Washington Mall, but three remarkable things then happened: the courts imposed a ban on Mall camping, the veterans simply ignored it and the Washington police did nothing to enforce it.

Before both Nixon and Haldeman were reports of media coverage of Kerry and the veterans, which was extensive and for the most part favorable. According to the official audiotape of their conversation, both were impressed by Kerry’s performance, and both realized that it only made their job harder. They were still responsible for prosecuting a war and for running a country that was quickly losing confidence in their leadership.

Nixon: “Apparently, this fellow, uh, that they put in the front row, is, that you say, the front, according to [White House aide Patrick] Buchanan . . . ‘the real star was Kerry.’”

Haldeman: “He is, he did a hell of a job.”

Nixon: “He said he was very effective.”

Haldeman: “I think he did a superb job at the Foreign Relations Committee yesterday. . . . A Kennedy type—he looks like a, looks like a Kennedy and talks exactly like a Kennedy.”

Kerry had hit the White House with the force of an unwelcome guest. He demanded an end to the war. Impossible, for Nixon. He demanded access to an administration official. Denied. He demanded a total change in policy. No way. “Disgraceful!” Kerry later told reporters. “We had men here with no legs, men with no arms, men who got nine Purple Hearts, and they ignored that simply because of the politics.” Ironically, Kerry had impressed Nixon so much that the president decided to take even stronger action against the demonstrating veterans.

David Thorne, once Kerry’s brother-in-law and now a close friend and adviser, told me that “the White House was sending out guys to start fights and to try anything they could do to discredit vets on the Mall. . . . We heard that Nixon was nuts about this. He was doing things in the dirty tricks department.” Brinkley said that the administration created a “get John Kerry campaign.” The exact words of a memo from White House special counsel Chuck Colson were: “I think we have Kerry on the run . . . but let’s not let up, let’s destroy this young demagogue before he becomes another Ralph Nader.’” Columnist Joe Klein, who covered Kerry at the time, reported: “They were investigating John Kerry up and down and Colson said to me, ‘We couldn’t find anything. There wasn’t anything we could find.’” Colson concocted the crazy idea of finding another John Kerry to destroy the real John Kerry. “We found this guy John O’Neill to run a group that would counter the Vietnam Veterans Against the War.” O’Neill was also a Swift Boat veteran, but he believed in the war and hated Kerry. They called the new group “The Vietnam Veterans for a Just Peace.” Just as O’Neill was central to derailing Kerry’s 2004 run for the presidency, so too was he central to Nixon’s effort to undermine Kerry in 1971. O’Neill met with administration leaders, including the president. “Give it to him,” Nixon urged. “Give it to him. And you can do it because you have a—a pleasant manner. And I think it’s a great service to the country.” Colson helped O’Neill organize media interviews around the country.

More White House audiotape shows Colson trying to buck up Nixon’s sagging spirit:

Colson: “And this boy O’Neill, who is, God, you’d just be proud of him. These young fellows, we’ve had some luck getting them placed.”

Nixon: “Have you?”

Colson: “Yes, sir.”

Nixon: “Good.”

Colson: “And they’ll be on. We’ll start seeing more of them. They would give you the greatest lift.”

The White House was obviously concerned that Kerry was becoming too much of a television star, spreading his antiwar message from one program to another. The White House was also concerned that the VVAW was generating too much sympathy and support. The war was still in progress, yet here were veterans demonstrating against it. They had come from all over the country, many in khaki, bearded, wearing headbands and sporting antiwar slogans on their T-shirts. Several were on crutches, a few in wheelchairs. On occasion, because there was no violence, they looked like respectable hippies promoting an antiwar message, some armed with nothing more lethal than a guitar. They marched through Washington, past the Lincoln Memorial, past the State Department, past the White House. Once, according to CBS correspondent Bruce Morton, who covered the week-long demonstration, “They passed some smiling members of the Daughters of the American Revolution, and a woman said: ‘This will be bad for the troops’ morale,’ and someone answered, ‘These are the troops.’” A national poll at the time revealed that one in three Americans approved of the VVAW’s demonstration, hardly an overwhelming number, but still encouraging to the VVAW’s leadership, including Kerry, who knew they had started from nowhere and now found themselves at 32 percent. Not bad for one week’s work. Forty-two percent disapproved. With the nation at war, the White House had expected a higher level of disapproval.

ON FRIDAY, April 23, the last day of the Washington demonstration, a hundred or so veterans threw their medals over a hastily built fence near the Capitol in a show of anger and disgust. Kerry threw ribbons, not medals. One veteran, making no distinction, said: “I got a Silver Star, a Purple Heart . . . eight air medals, and the rest of this garbage. It doesn’t mean a thing.”

If it didn’t “mean a thing” to this veteran, it did to many White House supporters, who, fearing their popular support dwindling, quickly denounced this display of anger as disrespectful to both the country and to the troops still fighting in Vietnam. Senate Minority Leader Hugh Scott, a Pennsylvania Republican, dismissively described these veterans as only “a minority of one-tenth of one percent of our veterans. I’m probably doing more to get us out of the war than these marchers.” Commander Herbert B. Rainwater of the Veterans of Foreign Wars chimed in with a double put-down: the antiwar veterans were too small a group to generate so much news, and besides they were not representative of the average veteran. Conservative columnist William F. Buckley Jr. trashed Kerry as “an ignorant young man,” who had crystallized “an assault upon America which has been fostered over the years by an intellectual class given over to self-doubt and self-hatred, driven by a cultural disgust with the uses to which so many people put their freedom.”

Nixon appreciated these measured expressions of support. With the war on the front burner of popular concern, sparking one Washington demonstration after another (one day after the VVAW’s protests, known as Dewey Canyon III, ended, a huge peace march arrived in the nation’s capital), Nixon yearned for good news, for the joys of a long weekend at Key Biscayne, but could find little in those days that could be defined as good. And Dewey Canyon III reminded him of a recurring nightmare that, though he tried, he could not escape. He worried that some Vietnam veterans might be returning not as the “monster” Kerry described, but as drug addicts. In his splendid biography of Nixon, journalist Richard Reeves wrote that the president’s worry was political. Reeves explained:

What worried him most was the effect on Middle American support for the war if clean-cut young men were coming back to their mothers and their hometowns as junkies. Suddenly drug use was a national security crisis. “This is our problem,” wrote Nixon on a news summary report of a Washington Post story that quoted the mayor of Galesburg, Illinois, saying that almost everyone in that conservative town wanted their sons out of Vietnam.

NBC News reported that half of a contingent of 120 soldiers returning to Boston had drug problems. The San Francisco Chronicle reported that each day 250 soldiers were returning with duffel bags full of drugs—as Reeves put it, “for their own use or to sell when they got back home.”

“As Common as Chewing Gum” was the way Time headlined a story about drug use by the troops. A GOP congressman, Robert W. Steele of Connecticut, told the White House that, based on his recent visit to Vietnam, he estimated that as many as forty thousand troops were already addicts. In some units, he said, one in four soldiers was a drug user. By May 16, the problem worsened, and the New York Times headlined its story “G.I. Heroin Addiction Epidemic in Vietnam.”

On the Washington Mall, however, it was not drugs that disturbed Nixon; it was the immediate problem of the antiwar message that Kerry and the veterans were pushing. Day after day, they dominated the evening newscasts and the morning headlines, and Congress—ever sensitive to media swings—felt emboldened to press forward with legislation to end America’s involvement in Vietnam. It would take another two years for Congress to achieve that goal, and another four years for the United States finally to leave Vietnam, its tail between its legs. But Kerry felt that the continuing VVAW effort was paying big dividends. During the Detroit conference, which he attended, and during Dewey Canyon III, which he helped lead, Kerry felt that the whole country was moving toward a historic decision to end the war. Since that was his goal, he was pleased. But he was soon to learn, as was the entire nation, that ending a war in defeat, or what was widely perceived to be a defeat, would prove to have a profoundly disruptive effect on a proud people who had never before experienced the trauma of losing a war. The French had lost wars, as had the Russians, Germans and Japanese, but never the Americans, not until they bumped into Vietnam.

WHEN KERRY returned to Boston a few days later, after the Washington demonstrations, he was in high spirits. His testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and his frequent appearances on television news and interview programs had propelled him into the national limelight and rekindled his political ambitions, which were never far from the surface in any event. He embarked on a nonstop speaking tour from one end of the country to the other, sparked by frequent TV debates with John O’Neill. One, on the Dick Cavett Show, attracted particular attention. O’Neill was strident, Kerry scholarly, clearly more adept at using television to fashion an image and project a message. “We knew that when he left the set,” Cavett recalled the occasion years later, “it wasn’t the last we were going to hear from him.” Kerry kept popping up on one program after another, selling himself as much as his antiwar theme. In a typical week, which happened to be the first week of October, Kerry spoke in Washington, DC, Kansas, Colorado, Nevada, California, Illinois and Massachusetts.

Throughout his whirlwind speaking tour, though, Kerry had one lingering problem, to which he returned time and again. He worried that the VVAW leadership was swinging too far leftward. If it continued to talk and act radical, it would lose the American people. Once during Dewey Canyon III he spotted a placard calling for “revolution.” Often he found himself arguing with other demonstration leaders about tactics. A few advocated violence; one even wanted to assassinate prowar senators rather than simply throw medals over a fence. Kerry, according to Randy Barnes, another key player, “constantly gave an impassioned plea to be nonviolent, work within the system.”

This problem came to a head at two VVAW meetings—in St. Louis in June and in Kansas City in November. Kerry attended the St. Louis meeting, and he may have attended the Kansas City meeting, too. (Some veterans remember him being there, while others swear he wasn’t.) What is indisputable is that Kerry left the St. Louis meeting, which was marked by hot arguments about the future direction of the VVAW, convinced that he had failed to persuade the leadership of this antiwar movement of veterans to stay “nonviolent” and to “work within the system.” A number of radical veterans wanted to initiate what the FBI later termed a “vastly more militant posture.” Kerry believed that there was a clear line separating antiwar sentiment from anti-American actions—these veterans, he thought, were moving dangerously close to that line. Kerry decided to resign from the executive committee of the VVAW, citing “personality conflicts and differences in political philosophy.”

From 1972, when he ran unsuccessfully for Congress, until 2004, when he ran unsuccessfully for president of the United States, Kerry’s world was intimately entangled with Vietnam. The seat for the Fifth Congressional District of Massachusetts opened when Republican F. Bradford Morse accepted the post of under-secretary-general of the United Nations. Morse promoted Paul Cronin, his legislative assistant, as the Republican candidate, and Kerry, sensing a superb opportunity to capitalize on his antiwar popularity, leaped into the fight as the Democratic candidate. Independent Roger Durkin, an investment banker, also entered the race. He ran ads sharply critical of Kerry’s liberal, antiwar positions, saying it was “important to defeat the dangerous radicalism that John Kerry represents.” He went further, actually questioning Kerry’s patriotism. Cronin watched from the sidelines, but the Sun, an archly conservative newspaper in Lowell, got behind Durkin’s attacks. An editorial blasted The New Soldier, a book Kerry had written about Dewey Canyon III. The book’s cover showed six veterans, bearded, with mustachios and headbands, looking like Castro warriors, holding up an American flag. The editorial, noting that the flag was being “carried upside down in a gesture of contempt,” angrily stated: “These people sit on the flag, they burn the flag . . . they all but wipe their noses with it.” Kerry tried to explain that an upside-down flag was a distress signal in international communications, not a sign of disrespect or contempt, but his explanation fell on deaf ears. Variations on this editorial ran in the Sun almost every day. Kerry fumed: “They were trying to paint a picture of me as some wild-assed, irresponsible, un-American youth. It was infuriating.” Kerry was to read similar editorials many more times over the years.

Then came the surprise that turned the election from a likely Kerry victory to a disheartening defeat. At the last minute, Durkin withdrew, throwing his support to Cronin, who gratefully accepted it. Kerry had been leading in the polls, but Durkin’s last-minute switch upset all political calculations. Cronin won; Kerry lost. The Boston Globe reported the next morning that Nixon, when told that Kerry had been beaten, slept like a baby.

IN 2004, it was not Durkin the man who resurfaced to defeat Kerry—it was his message, transmitted through the media by a well-financed veterans group called “The Swift Boat Veterans for Truth,” that undercut Kerry and destroyed his presidential prospects. The group was led by none other than John O’Neill. His hard-edged message, never wavering, echoed through time: Kerry was unpatriotic, he betrayed the nation and the veterans, he collaborated with the enemy and he was a traitor. And why? Because he used the Senate Foreign Relations Committee in April 1971 as a platform for criticizing American policy in Vietnam and, worse, for trashing the American warrior there as a brutal rapist who cut off ears and heads, shot at civilians, razed villages, and shot cattle and dogs for fun—all “in fashion reminiscent of Genghis Khan.” O’Neill and company had not forgotten Kerry’s testimony in room 4221.

From Nixon to Bush, conservatives used this line of attack against Kerry’s sharp critique of the Vietnam War, often questioning his patriotism and loyalty. Initially, Kerry and his friends considered it a sick joke. David Thorne recalled: “We both laughed at the fact that the President of the United States was after John.” Government agents shadowed Kerry at rallies and speeches. “It was just unbelievable,” Thorne told me. “He was as patriotic a guy as Yale University and the U.S. Navy ever produced. . . . I had come from a Republican family. Patriotism was in my veins. So we just thought because the war should end didn’t mean we deserved to have our basic rights infringed upon.” After a while, the joke was not funny. Kerry had raised a profound question—“How do you ask a man to be the last man to die for a mistake?” If the Vietnam War was a mistake, as Kerry believed, then there was no point in wasting additional lives. Let the “last man” really be the last man to die for a mistake. Nixon as president could not answer the question without either denying that the war was a mistake or admitting that it was. Denying meant, in effect, a continuation of the war; admitting meant an end to the war. He chose to do neither. Like an old political fighter, Nixon was content to engage, defeat and destroy Kerry, and he pulled no punches in this determined effort. Dissent was translated as opposition not only to his policy but to the nation and its destiny. Nixon was convinced he was right.

Kerry approached the argument from a different perspective. He believed his dissent on Vietnam was borne of his bloody experience there—it was not an academic exercise. He also believed that his dissent was in a noble American tradition. As Paul Revere and John Adams had objected to the king’s rule, so Kerry was objecting to the president’s policy. It was a moral obligation of the patriot to help his country face and correct a terrible mistake. His criticism was not intended to offend his countrymen but rather to help them emerge from the darkness of this blunder in Southeast Asia into the bright light of a better policy, consistent with the noble principles of American freedom.

What we saw emerging in the troubled year of 1971 was a new set of battle lines around two old issues—a definition of patriotism that fit the times and the changing value of military service as an asset for presidential leadership. On patriotism, dueling definitions were angrily debated without resolution but with a deepening bitterness that reflected the divide in the nation’s politics. On the value of military service, the pain of Vietnam shattered the old, comfortable conviction that service in uniform, under fire in the nation’s defense, strongly enhanced a candidate’s image of presidential authority and leadership.

Marvin Kalb is a guest scholar at the Brookings Institution and Edward R. Murrow Professor Emeritus at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. Over his thirty-year broadcast career, he served as CBS’s and NBC’s chief diplomatic correspondent, Moscow bureau chief and moderator of Meet the Press. His most recent book is The Road to War: Presidential Commitments, Honored and Betrayed, from which this article is adapted.

Image: Pullquote: From 1972, when he ran unsuccessfully for Congress, until 2004, when he ran unsuccessfully for president of the United States, Kerry’s world was intimately entangled with Vietnam.Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: From 1972, when he ran unsuccessfully for Congress, until 2004, when he ran unsuccessfully for president of the United States, Kerry’s world was intimately entangled with Vietnam.Essay Types: Essay