Feeling Bored? Here Are Five Detective Novels to 'Investigate' During Lockdown

A good detective story can get our minds running.

If COVID-19 has taught us anything, it’s that humans are connected, and that an individual’s actions can have profound consequences for the local community, the nation, and beyond. A good detective story, whether it takes place within an English country house or travels across international borders, reminds readers of this fundamental truth.

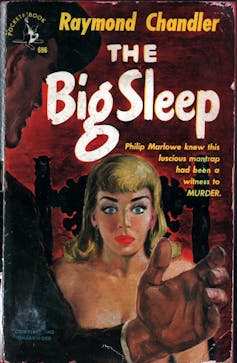

Detectives might be charming, eccentric amateurs like Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple, Dorothy L. Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey, for example – or tough, world-weary professionals such as Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe or Ian Rankin’s John Rebus.

But in both country-house and hard-boiled traditions their function is similar. They link disparate individuals and communities as they reconstruct events, and raise the possibility that, whoever pulled the trigger or administered the poison, we all share some responsibility for allowing such things to happen.

The selection below, I hope, reflects the genre’s diversity. What connects these books, for all their stylistic variety, is a preoccupation with links between people and communities and a desire to explore the implications of every action, deliberate or accidental.

Metta Fuller Victor: The Dead Letter (1866)

The first full-length detective novel in American literature, The Dead Letter, published under the pen-name Seeley Register, is a curious hybrid. Featuring a country house that might be haunted, a clairvoyant child who – conveniently – is the detective’s daughter, and scenes of deathly pale women wandering moonlit gardens, mourning lost lovers, it shows how 19th-century detectives emerged from Gothic literature.

It is also a sentimental love story and a meditation on the corrupting power of money.

Like the Edgar Allan Poe stories which influenced it, and the Sherlock Holmes tales that followed, its narrator is not the detective, but the detective’s friend who – like the reader – is inclined to romanticise the sleuth’s heightened abilities.

The Dead Letter can be florid and outlandish, but it combines its eclectic elements to highly entertaining effect.

Raymond Chandler: The Long Goodbye (1953)

Philip Marlowe, the hero of seven novels and numerous short stories by Raymond Chandler, is tall, handsome, witty and admirably cynical about the effects of wealth. I’d love to recommend all the Marlowe stories and, given that its author intended it to be the last, The Long Goodbye might seem an idiosyncratic choice.

Stranger still, its pleasures are less to do with the detective thriller’s traditional virtues – intricate plotting, dynamic action – and more with the air of nostalgic melancholia Chandler conjures. There are murders, of course, and there is the vivid evocation of Los Angeles in its grubby splendour. There is also Marlowe’s trademark gift for metaphor: at the beginning, watching two people arguing outside a club, he remarks:

The girl gave him a look which ought to have stuck at least four inches out of his back.

But the novel’s heart is the unlikely friendship between Marlowe and Terry Lennox, a rich, dipsomaniac veteran locked in a loveless marriage, emotionally scarred by his combat experiences. As its title suggests, this epic and heartbreaking novel is about goodbyes: to innocence, to friendship, to the conventions of the detective story, and to an America untainted by consumerism.

Agatha Christie: Cat Among the Pigeons (1959)

Christie remains the pre-eminent writer of the “whodunit”. Her sheer prolificacy masks the fact that she is a consistently innovative plotter, unafraid to experiment with point-of-view in sometimes radical ways. She also produces stories that are dark, disturbing, and morally ambiguous – characteristics highlighted in recent adaptations such as the BBC’s version of The Pale Horse.

Though not among her most celebrated novels, Cat Among the Pigeons delightfully combines international espionage and country house mystery, with the “country house” being a prestigious girls’ prep school in England where members of staff start dying in suspicious circumstances.

Ingenious and laced with cruelty, it might be read as a story about Great Britain’s declining empire, or the fragile isolation of the upper classes, or it might simply be read as Mallory Towers with added murder.

Paul Auster: The New York Trilogy (1987)

This comprises three distinctive tales: City of Glass, Ghosts and The Locked Room, that conspire to connect in surprising ways. Often regarded as a model of “antidetection”, Auster’s trilogy frequently confounds expectations, promising stock elements of the hard-boiled story – the enigmatic loner gumshoe, the femme fatale, the dirty city – before jettisoning the cliches and exploring new territory.

Auster’s New York is a labyrinth ruled by chance, where one’s doppelganger can appear for no reason, where a man can devote his life to collecting and renaming bits of rubbish, and where “Paul Auster” can appear as a character. These are elaborate puzzles yet highly readable thrillers.

They are perfect stories for lockdown because they are about the consolations of reading and the paradoxical truth that the deeper into solitude we go, the more we understand our vital connection to others.

Walter Mosley: Devil in a Blue Dress (1990)

This is the first thriller starring Ezekiel “Easy” Rawlins, an African-American factory worker in the Watts area of Los Angeles, who falls into detection when a stranger enters his local bar and offers him a missing persons job. Mosley’s work exemplifies the ways in which detective stories, tightly bound to specific places and times, function not only as entertainment but also as historical documents.

Devil in a Blue Dress, through energetic vernacular dialogue, realistic situations and wry observations on race relations, brilliantly evokes the lives of African-American families who moved from the southern states to California during the Second Great Migration.

More than the talented amateurs of the country house mystery, who possess a timeless quality and whose successful investigations tend to reinstate cosy normality – and Marlowe, a 20th-century knight errant with a nostalgic impulse – Easy Rawlins demonstrates that detectives are shaped by historical circumstances. He also happens to have one of the most captivatingly unstable sidekicks in all detective writing.

Detectives are people who move, tracing links between people, places and times. They are also expert readers: of clues, people, situations. During lockdown, these stories can transport us elsewhere and remind us that reading is an empathetic act, a way of reaching out and trying to connect with others.

![]()

James Peacock, Senior Lecturer in English and American Literatures, Keele University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters