Before Nobels: Gifts to and From Rich Patrons Were Early Science’s Currency

Collaborative scientific societies, beginning in the mid-17th century, distanced rewards from the whims and demands of individual patrons.

While the first Nobel Prizes were handed out in 1901, rewards for scientific achievement have been around much longer. As early as the 17th century, at the very origins of modern experimental science, promoters of science realized the need for some system of recognition and reward that would provide incentive for advances in the field.

Before the prize, it was the gift that reigned in science. Precursors to modern scientists – the early astronomers, philosophers, physicians, alchemists and engineers – offered wonderful achievements, discoveries, inventions and works of literature or art as gifts to powerful patrons, often royalty. Authors prefaced their publications with extravagant letters of dedication; they might, or they might not, be rewarded with a gift in return. Many of these practitioners worked outside of academe; even those who enjoyed a modest academic salary lacked today’s large institutional funders, beyond the Catholic Church. Gifts from patrons offered a crucial means of support, yet they came with many strings attached.

Eventually, different kinds of incentives, including prizes and awards, as well as new, salaried academic positions, became more common and the favor of particular wealthy patrons diminished in importance. But at the height of the Renaissance, scientific precursors relied on gifts from powerful princes to compensate and advertise their efforts.

Galileo presents an experiment to a Medici patron. Giuseppe Bezzuoli

Presented to Please a Patron

With courtiers all vying for a patron’s attention, gifts had to be presented with drama and flair. Galileo Galilei (1564-1642) presented his newly discovered moons of Jupiter to the Medici dukes as a “gift” that was literally out of this world. In return, Prince Cosimo “ennobled” Galileo with the title and position of court philosopher and mathematician.

If a gift succeeded, the gift-giver might, like Galileo in this case, be fortunate enough to receive a gift in return. Gift-givers could not, however, predict what form it would take, and they might find themselves burdened with offers they couldn’t refuse. Tycho Brahe (1546-1601), the great Danish Renaissance astronomer, received everything from cash to chemical secrets, exotic animals and islands in return for his discoveries.

Swedish inventor Alfred Nobel’s profile is on the medals awarded to the recipients of the prizes he established. Erik Lindberg

Patrons often bestowed gold portrait medals with their own images, a form that survives in the Nobel medal to this day. The medal usually came on a chain that could be sold, but the recipient could not cash in on patron’s image itself without offense.

Regifting was to be expected. Once a patron had received a work he or she was quick to use the new knowledge and technology in their own gift-giving power plays, to impress and overwhelm rivals. King James I of England planned to sail a shipful of delightful automata (essentially early robots) to India to “court” and “please” royalty there, and to offer the Mughal Emperor Jahangir the art of “cooling and refreshing” the air in his palace, a technique recently developed by James’ court engineer Cornelis Drebbel (1572-1633). Drebbel had won his own position years earlier by showing up unannounced at court, falling to his knees, and presenting the king with a marvelous automaton.

A version of Drebbel’s automaton sits on the table by the window in this scene of a collection. Hieronymous Francken II and Brueghel the Elder

Searching for Better Incentive Structures

Gifts were unpredictable and sometimes undesired. They could go terribly wrong, especially across cultural divides. And they required the giver to inflate the dramatic aspects of their work, not unlike the modern critique that journals favor the most surprising or flashy research leaving negative results to molder. With personal tastes and honor at stake, the gift could easily go awry.

Scientific promoters already realized in the early 17th century that gift-giving was ill-suited to encouraging experimental science. Experimentation required many individuals to collect data in many places across long periods of time. Gifts emphasized competitive individualism at a time when scientific collaboration and the often humdrum work of empirical observation was paramount.

While some competitive rivalry could help inspire and advance science, too much could lead to the ostentation and secrecy that too often plagued courtly gift-giving. Most of all, scientific reformers feared an individual would not tackle a problem that couldn’t be finished and presented to a patron in his or her lifetime – or even if they did, their incomplete discoveries might die with them.

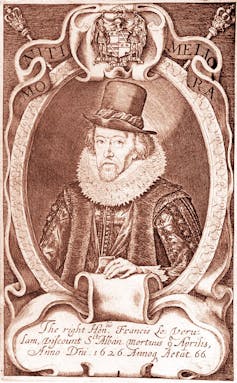

Francis Bacon saw the need for better incentive systems in science. Frontispiece of Sylva sylvarum

For these reasons, promoters of experimental science saw the reform of rewards as integral to radical changes in the pace and scale of scientific discovery. For example, Sir Francis Bacon (1561-1626), lord chancellor of England and an influential booster of experimental science, emphasized the importance even of “approximations” or incomplete attempts at reaching a particular goal. Instead of dissipating their efforts attempting to appease patrons, many researchers, he hoped, could be stimulated to work toward the same ends via a well-publicized research wish list.

Bacon coined the term “desiderata,” still used by researchers today to denote widespread research goals. Bacon also suggested many ingenious ways to advance discovery by stimulating the human hunger for fame; a row of statues celebrating famous inventors of the past, for example, could be paired with a row of empty plinths upon which researchers might imagine their own busts one day resting.

Bacon’s techniques inspired one of his chief admirers, the reformer Samuel Hartlib (circa 1600-1662) to collect many schemes for reforming the system of recognition. One urged that rewards should go not only “to such as exactly hit the marke, but even to those that probably misse it,” because their errors would stimulate others and make “active braines to beate about for New Inventions.” Hartlib planned a centralized office systematizing rewards for those who “expect Rewards for Services done to the King or State, and know not where to pitch and what to desire.”

Moving Toward a More Modern Mode

Collaborative scientific societies, beginning in the mid-17th century, distanced rewards from the whims and demands of individual patrons. The periodicals that many new scientific societies started publishing offered a new medium that allowed authors to tackle ambitious research problems that might not individually produce a complete publication pleasing to a dedicatee.

For example, artificial sources of luminescence were exciting chemical discoveries of the 17th century that made pleasing gifts. A lawyer who pursued alchemy in his spare time, Christian Adolph Balduin (1632-1682), presented the particular glowing chemicals he discovered in spectacular forms, such as an imperial orb that shone with the name “Leopold” for the Habsburg emperor.

Many were not satisfied, however, with Balduin’s explanations of why these chemicals glowed. The journals of the period feature many attempts to experiment upon or question the causes of such luminescence. They provided an outlet for more workaday investigations into how these showy displays actually worked.

The societies themselves saw their journals as a means to entice discovery by offering credit. Today’s Leopoldina, the German national scientific society, founded its journal in 1670. According to its official bylaws, those who might not otherwise publish their findings could see them “exhibited to the world in the journal to their credit and with the praiseworthy mention of their name,” an important step on the way to standardizing scientific citation and norms of establishing priority.

Louis XIV surveys the members of the Royal Academy of Sciences in 1667. Henri Testelin

Beyond the satisfaction of seeing one’s name in print, academies also began offering essay prizes upon particular topics, a practice which continues to this day. Historian Jeremy Caradonna estimates 15,000 participants in such competitions in France between 1670, when the Royal Academy of Sciences began awarding prizes, and 1794. These were often funded by many of the same individuals, such as royalty and nobility, who in former times would have functioned as direct patrons, but now did so through the intermediary of the society.

States might also offer rewards for solutions to desired problems, most famously in the case of the prizes offered by the English Board of Longitude beginning in 1714 for figuring out how to determine longitude at sea. Some in the 17th century likened this long-sought discovery to the philosophers’ stone. The idea of using a prize to focus attention on a particular problem is alive and well today. In fact, some contemporary scientific prizes, such as the Simons Foundation’s “Cracking the Glass Problem,” set forth specific questions to resolve that were already frequent topics of research in the 17th century.

The shift from gift-giving to prize-giving transformed the rules of engagement in scientific discovery. Of course, the need for monetary support hasn’t gone away. The scramble for funding can still be a sizable part of what it takes to get science done today. Succeeding in grant competitions might seem mystifyng and winning a career-changing Nobel might feel like a bolt out of the blue. But researchers can take comfort that they no longer have to present their innovations on bended knee as wondrous gifts to satisfy the whims of individual patrons.

![]()

Vera Keller, Associate Professor of History, University of Oregon

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.