The Rwanda-Burundi, Hutu-Tutsi Conflict Is Far From Over

How is the past of the two Hutu-Tutsi countries likely to influence their future?

Most of us might be accustomed to the 1994 Rwandan genocide popularized by the Hollywood movie Hotel Rwanda in which the shooting down of President Juvenal Habyarimana’s plane was used as a signal to execute a planned killing of Tutsis by Hutus. However, the Rwandan case is not the first case of genocide in the Great Lakes region. The region’s first occurred in neighboring Burundi in July 1972, in which about 200,000 to 300,000 Hutus were killed by Tutsis using an abortive Hutu insurrection as a trigger. In-between these two, several other planned mass killings between the two groups, in turn, have taken place. Neither Rwanda nor Burundi can be mentioned independently of the other when examining the Hutu and Tutsi groups. Moreover, any discussion of the two groups—whether on the basis of ethnicity or social caste—that seeks to examine the long-held hatred between them cannot ignore the anti-Tutsi, anti-monarchical Hutu Revolution in Rwanda between 1959 and 1962, or some few years preceding that. This period shaped a Hutu-Tutsi identity-based hatred upon which all other hatred and mass killings revolve.

We all have different requirements for making friends or enemies in our immediate environment. While the formation of friendship is difficult—although not impossible especially when there are shared in-group characteristics—for the realist paradigm of international relations, liberalists claim those who share liberal principles such as democratic values and ideas make good friends and most often do not fight each other. The constructivist conceives of a friend or enemy as socially constructed. Thus, identity defined in terms of culture, traditions, religion, norms, and values bind people and make them gravitate towards one another. Identity helps to define or make a distinction between friend and enemy. Who I am or we are and what I do or we do depends on who my or our friend or enemy is. A friend or enemy formed on the basis of identity is not only private but transcends the individual to become public friend or enemy. What is most important in friend-enemy formation is that we could see an element of identity in all paradigms. An enemy to the constructivist is based on an emotional feeling of someone who has hurt him (private enemy) or his identity (public enemy) in the past. Choosing between conflict and concord, an extreme enemy is more likely to make the former option to be able to maximize brutality and possible killing.

How is the past of the two Hutu-Tutsi countries likely to influence their future? The cycle of Hutu-Tutsi genocide or mass killings of each other in turn, in the Great Lakes region, particularly Rwanda and Burundi, has created past memories and emotional feelings of identity-based hatred that will likely continue to haunt both countries’ future and shape more Hutu-Tutsi identity-based conflict.

Precolonial Rwanda and Burundi were highly centralized. Nevertheless, it should not be assumed that the centralized system was all of equality and harmonious living. In Rwanda, the society was already stratified where Hutu peasants, approximately 85 percent of the population, were at the bottom of the system, and at the top of power and wealth was the minority Tutsi. This does not mean that every Tutsi was powerful and wealthy and every Hutu poor and vulnerable, but inequality was shown in the differential treatment across and within the groups. In Burundi, the power holders were a distinct category of princes descended from the king and not a straightforward Hutu-Tutsi division. The Tutsi themselves were subdivided—Tutsi-Hima and Tutsi-Banyaruguru, the latter being more prestigious than the former. Despite the inequalities in the two countries, the system was effective and the two groups shared culture, language, traditions, and gods that unified them. With such inequality, it cannot be denied that there was a potential for rebellion and conflict as Catharine Newbury argued, but it did not happen prior to colonial rule so we cannot make a case for it.

It was Belgian colonial rule that altered the norms, created and shaped sharp ethnic identities out of socioeconomic stratification, and made it rigid, or at least, codified an unequal relationship into an oppressive hate system. In both countries, colonial rule acting through Tutsi monarchy reserved all opportunities exclusively for the Tutsis, whom, the colonial system regarded as elegant and superior. The system became rigid, obnoxious, and biased against the Hutu. Oppression is most likely to engender rebellion. Thus, Rwanda’s independence struggle that ended colonial and monarchical rule became an ethnic struggle between Hutu and Tutsi. An anti-Tutsi, anti-monarchical revolution erupted in 1959 in which thousands of Tutsis were massacred and thousands more fled to neighboring Burundi, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, and Tanzania culminating in the 1962 Rwandan Independence. Although Burundi was spared revolution, the thousands of Tutsis who fled Rwanda and entered Burundi, each with tales of horror to tell, shaped events there. It created a demonstration effect, an inspiration for both Hutu and Tutsi in Burundi. For Hutus, Rwanda became a model to emulate. For Tutsis, Rwanda evoked a fate to be avoided which resulted in greater suspicion and repression.

Hutu anger in Burundi broke out in 1965 in an abortive coup. Although it was aborted, several Tutsis were attacked and killed while many fled. Between 1965 and 1969, a Tutsi-dominated army repressed the carnage with revenge killing of Hutu masses and key personalities which resulted in more refugees across borders. In April 1972, another Hutu-led rebellion that first led to the mass killing of Tutsis by Hutus was met by Tutsi-dominated army repression that resulted in a genocide in which not fewer than 200,000 Hutus were killed while thousands more fled to Tanzania and Hutu-controlled Rwanda. By August, a systematically planned and executed massacre had either annihilated every educated Hutu including civil servants, university students, and secondary and basic schoolchildren or sent them into exile as well as Hutu officers and troops. According to Rene Lemarchand, vehicles drove up to schools to pack-up Hutu schoolchildren to kill while neighbors killed to appropriate victims’ properties. A number of Tutsi refugees from Rwanda accepted the task for revenge. The aim was to eliminate all forms of future challenge to Tutsi rule.

In Rwanda, the Tutsi refugees including the previous powerholders who fled during the anti-monarchy revolution attempted to return militarily, launching guerrilla attacks from Burundi and Uganda between 1961 and 1964. Whiles repressing the attacks, the first Hutu regime under President Gregoire Kayibanda (1962-73) also planned and killed innocent Tutsi civilians. According to Peter Uvin, between 140,000 and 250,000 were killed while 70 percent of the survivors fled. In Burundi, Tutsi regimes under Michel Micombero to Pierre Buyoya held sway. In August 1988, another Hutu riot triggered by rumors of an impending massacre of Hutus killed hundreds of Tutsi civilians until it was once again met by Tutsi army repression. According to Totten et al., about 40,000 fled while between 20,000 and 30,000 were massacred. Bowing to international public condemnation and diplomatic pressure particularly from the European Community and the U.S. Congress, Burundi under Buyoya (1987-93) began political reforms that resulted in the 1993 elections. The predominantly Hutu Front des Democratic du Burundi (Frodebu) scored a landslide victory to wrest power from the Tutsis. However, in October 1993, the Hutu Burundian president was assassinated by Tutsi extremists, inciting anti-Tutsi violence killed about 25,000 Tutsi. The army, still dominated by Tutsis, killed as many Hutus as possible in retaliation that resulted in another genocide that sent thousands of Hutu refugees into Rwanda. Many of these refugees later joined the Rwandan pro-Hutu Interahamwe to execute the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

In Rwanda, the second regime led by General Habyarimana (1973-94) held sway using repression and all forms of brutality against Tutsi and as well as some Hutu opponents. Gerard Prunier shows that all positions in government and civil service were reserved for Hutus with only one Tutsi officer in the whole army. The descendants of the early 1960s Tutsi refugees were determined to come home through military force. Through their Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) led by Paul Kagame, they launched guerrilla attacks from Uganda with Kampala’s support in the 1990s. An October 1990 attack fashioned the RPF as a credible threat in the Rwandan government, which led to greater repression and brutality of Tutsi civilians. Anti-Tutsi violence increased in proportion to RPF attacks. Many of the Hutus who lost their homes in the northern towns as a result of RPF attacks joined the Hutu militia—Interahamwe—ostensibly to protect civilians but their real function came to be to “provide auxiliary slaughterhouse support“ to the police and army to annihilate all Tutsis. From April to July 1994, the Rwandan genocide, planned for years from the top echelon of government, was executed.

The RPF entered Rwanda at the peak of the genocide to kill and chase out the Interahamwe and the all-Hutu Rwandan Armed Forces (FAR) but did not end the genocide, rather starting a new wave. Between 1996 and 1997, the RPF is believed to have killed between 200,000–300,000 Hutus and by supporting rebel movements, particularly in DRC, as well as using political witch-hunting and intimidation as Rwandan opposition groups claim, the killings are believed to continue to today. Key personalities such as Paul Rusesabagina have leveled various accusations of “double genocide“ against Kagame’s regime.

The historical antecedents presented show a cycle in which in both Rwanda and Burundi, whichever group is in power at any particular time excludes and kills the other. Thus, the root cause of genocide in the Great Lakes Region lies in the extent to which collective identities have been mythologized and manipulated, making the Hutu-Tutsi hatred transcend individual enmity. It is more of who we are than who I am. Today, the Hutu-Tutsi classification is not just about ethnicity or socioeconomic caste, but rather, a kind of a divined classification that carries tremendous emotional charge in the heart but people have found ways to suppress it, at least for the meantime.

In Rwanda, a personal identification of either Hutu or Tutsi is frowned upon, but this is only on a superficial basis. People have been told this is how it should be, making this system one of the head and not the heart. I have personally had opportunities to talk with some Rwandan youth and although some few showed their identity, the majority claimed they have no idea of their identity. I wish this was true, but I have always doubted their answers in silence. The silence over who is who today is made possible by President Kagame’s strongman rule and claims that he is building an inclusive government, but the atrocities of yesterday are still in the people’s hearts. In any case, Kagame is not immortal. The crucial period is the transition in the advent of Kagame’s death. Thus, the next fifteen to twenty years will be telling. Yesterday’s atrocities have shaped Hutu-Tutsi identities of hatred, and thus, remain salient among the public. It is likely to continue to haunt the future of both countries for two main mutually inclusive reasons: fear and revenge.

Both Hutus and Tutsis are consumed by the fear of the unknown. Each is afraid that if he gets power and does not utilize it well by eliminating the other, the other will eliminate him when he gets the power. Each has no supernatural power to know what is in the mind of the other. It is a kind of defensive strategy that utilizes attack. Anyone who gets power engages in preemptive violence for the fear that he will lose it, lives, and livelihoods in massive violence by other. Revenge killing is also associated with all the various cases of mass killings reviewed. Revenge and fear shape each other. The historical killings have shaped a collective identity that makes it possible for each group in any country to attempt to avenge the death of kindred either within a territory or across the borders.

As a smart military man and a politician, President Kagame needs to put people he trusts in important sectors of Rwandan governance and these are obviously his Tutsi comrades to the exclusion of Hutu politicians. With Hutu rebels lurking and launching intermittent attacks from Burundi in attempts to take over power, it is difficult to argue that Hutu politicians and civilians are not supportive of them and, when the chance arises, they will not join the bandwagon—a charge that has landed Paul Rusesabagina in court facing charges of terrorism and murder. Today there is a Tutsi government in Rwanda and a Hutu one in Burundi and each is believed to harbor the other’s rebels in what I term as unholy alignment. In the advent that both regimes become either Hutu or Tutsi, it could also present unpalatable consequences. The cycle of fear and revenge killings has continuously shaped collective Hutu-Tutsi identities of hatred and constructed an enemy on the basis of past pain. I do not foresee why there wouldn’t be recurrent conflicts when fear and revenge are still significantly present. However, the next Hutu-Tutsi conflict is unlikely to have the same intensity and duration as the previous ones because of global public awareness, social media, and interest of the international community.

Thomas Ameyaw-Brobbey is an Assistant Professor of International Relations, Diplomacy and Security at the Faculty of Law and Public Administration, Yibin University, Sichuan, China

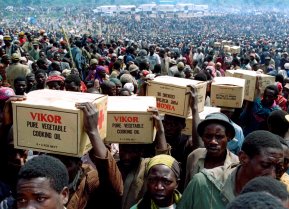

Image: Reuters.