Why Rolling Back Environmental Regulations During Coronavirus Is Short-Sighted

Short-term environmental damage can have long-term effects.

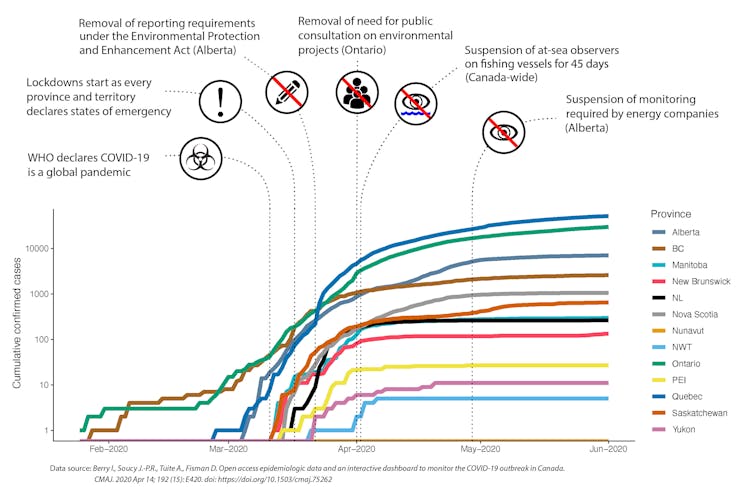

Many governments have used the distraction of the coronavirus pandemic to roll back environmental regulations. Governments have cited both public health rules and the economic challenges that companies are facing to defend their rollbacks.

Both the United States and Brazil have lifted limits on pollution, carbon emissions and forestry, and made it easier to approve pipelines. Governments in Canada have also used the COVID-19 crisis to curb environmental protections for communities and ecosystems.

But these changes can come with large risks. Although they may only last a few months, the environmental impact may be much longer. Short-term environmental damage can have long-term effects.

Alberta suspends monitoring requirements

There are situations, of course, where the rules need to change to decrease the spread of the coronavirus, such as when work requires travel to remote and vulnerable communities. But many of the changes made to environmental regulations have removed the requirements for environmental monitoring altogether or reduced or eliminated environmental observers, which means no data will be collected.

For example, Alberta suspended reporting requirements under several environmental acts, except for drinking water facilities. Later changes by the Alberta Energy Regulator removed many monitoring requirements for oil companies, including monitoring surface water, ground water and wildlife in tailings ponds.

The changes were requested by the oil industry so that companies could follow public health orders, but were passed without public consultation or reasons why the changes were needed for public health reasons. Given that spills can happen quickly, even small gaps in the data during a public health crisis may affect future decisions such as changing pollution limits or approving new projects.

Continuing activities such as mining or oil extraction without environmental monitoring is risky, both for the environment and for businesses. For example, Canada added stricter regulations for some mining waste products in 2018 after monitoring showed amounts previously allowed were harmful to local fish and habitats. Monitoring helped inform new rules to prevent more damage to the environment.

Even for businesses, environmental regulations are important. Environmental disasters pose a serious risk to a company’s reputation that can deeply impact sales and profits, as seen in BP’s fallout from the Deepwater Horizon oil spill. Regulations also ensure that businesses have a level playing field by spreading out the costs of environmental protection more fairly, so surely not all businesses support these recent changes.

At-sea observers disembark

Monitoring was also temporarily put on hold in fisheries. The at-sea observers who monitor what is being caught and discarded were suspended in Canada for 45 days. Without observers, it is much harder to know how sustainable a fishery is, and a monitoring gap could put endangered species at greater risk. In this case, the changes came without full input from industry, which relies on observers to ensure that all boats abide by the same rules and to increase public trust in resource management.

The aquaculture industry has also asked for flexibility in monitoring requirements, such as stopping counts of sea lice on salmon. It is not clear how monitoring in aquaculture will be disrupted, but demands such as this highlight attempts by some industries to capitalize on disaster, even if there is weak public health justification for lifting monitoring requirements.

Incomplete monitoring can also put human health at risk, such as when improper water monitoring in Walkerton, Ont., led to seven deaths and more than 2,300 people falling ill in 2000.

Ontario ends public consultation

Public participation is a key part of environmental protection, playing an important role in environmental assessments and protecting endangered species.

Some of the changes that have occurred in Canada since the start of the coronavirus pandemic have removed public participation in decision-making processes. For example, Ontario removed the requirements for consultation on environmental issues during the current state of emergency. Normally, projects that affect the environment have a 30-day consultation period.

The consultation period allows the public, including First Nations and scientists, to comment on proposed projects or policies, such as permits that could affect endangered species or the approval of mining projects. Public participation in regulatory discussions, like environmental assessments, is important to Canadians and part of fair and ethical environmental legislation. The changes in Ontario that limit public participation also lower transparency.

Recently, Alberta also opened much of the eastern Rocky Mountains and foothills to open-pit coal mining without public consultation. This change will limit public access to land to enjoy hiking, camping and fishing.

Technology can help

Making greater use of technology can allow monitoring even during crises. For example, the use of sensors and cameras on fishing vessels to monitor fishing activity and catches is increasing worldwide. In Canada, electronic monitoring is being used in at least three fisheries in British Columbia. Introducing this technology to other fisheries could prevent monitoring disruptions in the future.

Creating or expanding online platforms for public consultation and using remote-sensing instruments for monitoring pollution and wildlife can help lower human risk while maintaining environmental standards.

During the pandemic, environmental regulations have changed rapidly, and Canada has not been immune to pressures to lower environmental standards. But relaxing these standards places Canada’s communities and biological diversity at greater risk and so should only be done when the immediate public health risk is real. Where this cannot be demonstrated, the rollbacks should be reversed.

In cases where there is a public health concern, there also needs to be clear timelines so we do not add to the COVID-19 burden by putting the environment at risk. Moving forward, new technology can help shrink gaps in monitoring and maintain public participation in environmental decisions during crises.

![]()

James E Paterson, Liber Ero Fellow, Environmental and Life Sciences Program, Trent University; Brynn Devine, Postdoctoral research fellow, Department of integrative biology, University of Windsor, and Gideon Mordecai, Liber Ero Postdoctoral Fellow, Department of Medicine, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Image: Reuters