The Russian-American Deal of the Century

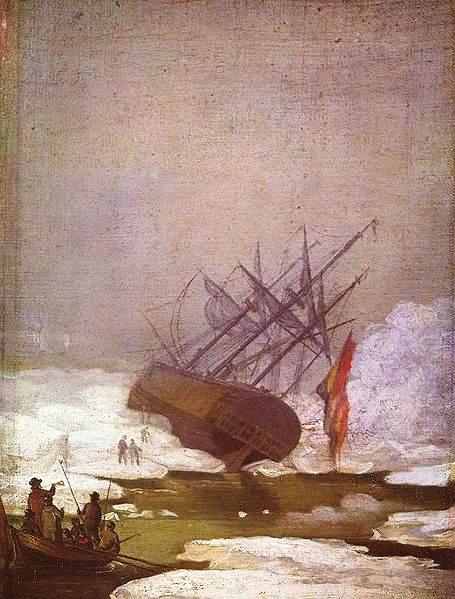

Caveat emptor—let the buyer beware—is the best policy Exxon can pursue while sailing the frigid Russian waters.

The retreat of the Arctic polar ice cap combined with technological advances now makes development of new oil fields in the High North possible. And two energy giants have announced they will search together for black gold along the Russian Arctic continental shelf in the Kara Sea.

The retreat of the Arctic polar ice cap combined with technological advances now makes development of new oil fields in the High North possible. And two energy giants have announced they will search together for black gold along the Russian Arctic continental shelf in the Kara Sea.

America’s largest oil company last week reached an historic agreement with Russia’s state oil company, Rosneft. ExxonMobil now will take the place of BP (British Petroleum), whose dealings with Rosneft collapsed earlier this year.

Negotiations between Rosneft and BP broke down over a stock swap intended to bypass BP's exclusive Russian partner TNK and their joint venture TNK-BP. The Russian partners in TNK blocked the swap through arbitration in Stockholm. Exxon offered an alternative. It agreed to make Rosneft a partner in its projects in the Gulf of Mexico and Texas in return for an equal share in the Russian projects.

The volume of transactions is enormous. By its own conservative estimates, Exxon believes it will need to invest over $3 billion in Arctic prospecting alone. Tens of billions more will be needed to get production started. Total direct investment for the project could reach as high as “$500 billion—a scary number,” according to Russian prime minister Vladimir Putin.

At present, Exxon is working with Rosneft at Sakhalin Island as part of “Sakhalin-1.” Reserves of “Sakhalin-1” are estimated at 300 million tons of oil and 500 billion cubic meters of gas. Exxon is working under a production-sharing agreement with the Russian state, which in the past was revised to Exxon’s detriment. Exxon is also cooperating with Rosneft on a Black Sea project off the Russian port of Tuapse. Experts have long said that exploration in the Black Sea would require at least $1 billion. The Arctic deal, meanwhile, is regarded as much riskier than Sakhalin and the Black Sea.

The risks of doing business with Russia are clear. Besides the harsh Arctic Ocean conditions, Exxon must take on implicit obligations important to the Russian side. Rosneft is still trying to absorb the remainder of the Yukos Oil Company's assets it acquired in 2005–2007, and those assets may yet be frozen for the benefit of Yukos' former shareholders (some of whom are U.S. citizens and corporations). Ironically, Exxon tried to buy half of Yukos when it was still owned by its founder, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who now languishes in a Russian jail.

The new deal with Exxon gives Rosneft and Russia the massive lobbying capabilities of a leading U.S. oil company. The deal of the century may seriously alter the geopolitical balance, moving the United States and Russia closer together.

But this arrangement will have to pass Washington’s scrutiny, as it is the first significant attempt by a Russian state-owned company to acquire stakes in U.S. oil fields. Russia is not an ally of the United States. However, with the “reset” policy with Moscow evidently failing, the U.S. administration may be tempted to ignore the risks Exxon is assuming to foster the impression that relations with Russia are on track. Yet, opponents of the deal may take their case before Committee on Foreign Investments in the United States.

There is also a domestic explanation to this deal. As the Wall Street Journal pointed out, since the U.S. government has virtually closed off all access to the enormous resources of the Arctic, partnering with the Russians offers American companies an alternate route to reach the energy riches of the High North. The irony is: Exxon will invest tens of billions of dollars in the Russian Arctic while the Arctic waters off the U.S. coast remain inaccessible due to environmental and bureaucratic obstacles.

Currently, American environmental regulation impedes economic expansion in the U.S. Arctic shelf. The American oil company Sunoco tried for five years to attain access to one of the sites in the National Petroleum Reserve but in the end was refused by the U.S. Corps of Engineers. Exxon ran into the same problems when it sought permission to work on Alaska's North Slope. The United States also lacks icebreakers to map and develop the frozen expanses of the Arctic.

In light of all these obstacles, it is not surprising that Exxon decided to risk an agreement with Rosneft. But judging by previous adventures of foreigners in Russia—especially in the oil sector—the path chosen by Exxon may prove difficult. Caveat emptor—let the buyer beware—is the best policy the American company can pursue while sailing the frigid Russian waters.