U.S. Strategy: Evolve or Perish

Thomas Jefferson's 21st century man cannot forever wear the clothes of his younger, 20th century self.

The answer we give to three questions will largely determine whether the United States will flourish or decline in the 21st century. First, will we anticipate events or merely react to them? Second, will we form new alliances to address new realities? Third, how rapidly will we adapt to transformational change?

The answer we give to three questions will largely determine whether the United States will flourish or decline in the 21st century. First, will we anticipate events or merely react to them? Second, will we form new alliances to address new realities? Third, how rapidly will we adapt to transformational change?

These questions share an assumption: the world is changing and it is changing fast. Our national predisposition, however, has been to rely on traditional institutions and policies and to use them to address unfolding history on our own timetable.

We also are inclined to employ a simple, all-encompassing, central organizing principle as a substitute for a national strategy. During the second half of the twentieth century that principle was containment of communism. After 9/11 it became war on terrorism. Unfortunately, the period in between, the largely peaceful and prosperous 1990s, was not used to develop a comprehensive strategic approach to an almost totally different new century that was emerging.

One lone effort represents the exception. The U.S. Commission on National Security for the 21st Century produced a road map for national security for the first quarter of the century. It was almost totally ignored and of its fifty specific recommendations only one, the creation of a Department of Homeland Security, has been adopted a decade later.

There are reasons for our lassitude, false sense of security, and reliance on reaction. Between 1812 and 2001 our continental home was not attacked. And because we are a large island nation, we have felt ourselves to be invulnerable. Our economic expansion between the end of World War II and the first oil embargo of 1974 created a very large, productive, and secure middle class. We have possessed economic and military superiority for well over a half-century. And for most of our history, strategic thinking and planning, especially on the grand scale, has been an enterprise confined largely to the academy. Instead, our policy makers would deal with events as they arose.

NO LONGER. Multiple revolutions will continue to remake the world for decades to come. Globalization—the internationalization of finance, commerce, and markets—is making national boundaries economically redundant. Information has replaced manufacturing as the economic base of our nation, and it is further integrating global networks. Both globalization and information are eroding the sovereignty of nation-states. And this erosion has contributed to the transformation of war and the changing nature of conflict.

In large part because of these multiple political, economic, and social revolutions, a host of new realities characterize the 21st century. These include failed and failing states, mass south-north migrations, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, the rise of ethnic nationalism and religious fundamentalism, the emergence of tribes, clans, and gangs as alternatives to the nation-state, the threat of pandemics, energy interdependence, the threat of global warming, and many other new phenomena.

It might be argued that this plethora of new realities suggests a wholly pragmatic, case-by-case response. It might better be argued, however, that now more than ever the United States requires a grand strategy that seeks to consistently apply its powers and resources to the achievement of its large purposes over time. For these new realities share two qualities: they cannot be adequately addressed by military means, and they cannot be solved by one nation alone.

Further, as events accelerate response times shorten. Deliberation, formation of ad hoc responses and coalitions, and sifting through alternatives, once a threat is immediate, all become luxuries. In this century events and their repercussions will not wait for us to organize ourselves and our allies. A strategy of ad hoc reaction will not work.

This being true, deduction alone dictates a strategy that is internationalist, one that appeals to the common interests of the like-minded (that is to say democratic) nations, one that anticipates, and one that requires burden-sharing among those who occupy a global commons. For it is the notion of a global commons, both actual and virtual, that must characterize America’s 21st century grand strategy.

THREE GUIDING principles might structure such a strategy: economic innovation; networked sovereignty; and integrated security.

First, the United States cannot play a constructive global leadership role without a fundamentally restructured economy. Global diplomatic engagement and international security cannot be financed with borrowed money. Neither true security nor leadership can be founded on debt. The only way for the United States to reliably pay for its international engagement and its security is by revenue it generates through its own creative economic activity.

For the time being the United States will remain superior in economic, political, and military terms. But it can maintain its leadership position over time only through economic innovation. We cannot continue to finance our military establishment with its far-flung operations by borrowing money from the Chinese and future generations. Though it is becoming a somewhat worn theme, it is nonetheless true: we must invest in science and technology, our universities and laboratories, corporate research, and multiple facets of innovation both to drive our own economic expansion and to market our innovations to the world.

Through the realignment of fiscal incentives and disincentives, the United States must transform itself from a debtor, consuming nation to a creditor, producing nation. Governments and peoples around the world will find an economically creative U.S. an attractive model to follow. That attraction ensures U.S. international leadership. That leadership can organize the security of the global commons.

Second, organizing America’s role in the world around the notion of a global commons requires identifying common threats before they become toxic and common interests requiring common pursuits in advance of threats. The primary resistant to the notion of a global commons is national sovereignty. But, as NATO proved following World War II and throughout the Cold War, shared security is not a threat to national identities and notions of self-governance.

There are a number of illustrations of how the security of the commons might work:

* The public health services of advanced nations can be networked by common databases and communications systems to identify and quarantine viral pandemics before they spread and to organize regional stockpiles of immunization agents to facilitate containment;

* An international constabulary force can be created, possibly under NATO auspices, to manage failing states and tribal conflicts while diplomats negotiate restructuring agreements. Rwanda, Darfur, and Kosovo in the past and Somalia, Sudan, and Libya today all suggest conflicts that could have been anticipated and might be managed with much less loss of life;

* The existing International Atomic Energy Agency could be strengthened to become the indispensable agency for inspection of suspected manufacturing and stockpiling of weapons of mass destruction. Its mandate should be enforced and expanded, as it was not in Iraq, by the U.S. and the international community;

* It is not too soon to design an administrative and enforcement mechanism for an international treaty on carbon reduction: a climate treaty will not be self-enforcing.;

* The most unstable region of the world, the Persian Gulf, is the source of a quarter of U.S. oil imports and a substantial amount of the importing world’s supplies. Currently, the U.S. is the de facto guarantor of those oil supplies as well as the broader sea lanes of communications. As a loose consortium of nations with shipping interests now seek to control piracy off the Somali coast, so a more tightly-knit consortium should share responsibility for policing the Persian Gulf and guaranteeing all importing nations’ oil supplies.

All these issues, and many more, represent the world of the 21st century, much more a global commons than a hodge-podge of fractious nations and percolating conflicts in constant tension. Stable nations will increasingly find common cause in reducing and where possible eliminating local conflicts before they fester and spread. Nations, especially powerful nations, will continue to arm themselves. But they will find it appealing, politically and financially, to network their military assets in pursuit of common security interests. As NATO represents the triumph of collective security in a Cold War century, so new realities now require new alliances beyond the capabilities and mandate that NATO represents in a new and different century.

Forming new alliances with emerging regional power centers offers several advantages. Regional powers can be made partners rather than antagonists or rivals. Identifying mutual and collective security interests with the U.S. and formalizing a collective approach to securing these interests empowers regional leaders further and signals that the U.S. respects their legitimate concerns. Formal regional security alliances create diplomatic and administrative structures that anticipate, rather than react to, new realities and threats in their respective regions.

Thus, a third pillar of America’s 21st century strategy is integrated security. While a creative economy provides the resources, we pursue our global security in and through the global commons which we lead. A strong consortium of twenty to thirty nations can anticipate and minimize threats from non-military realities and can confine local conflicts before they become viral.

Nations not sharing democratic principles and institutions will find it profitable to begin to adopt these principles and institutions as the price of shelter beneath the security umbrella of the global commons. Political accommodation to enter the commons will more than pay for itself in enhanced shared security, including protection from pandemics, control of dangerous weapons, climate stabilization, isolation of terrorism, guaranteed oil supplies, and stabilization of disintegrating states.

For example, there is every reason to create what I have called a zone of international interest in the Persian Gulf whereby a collection of major oil importing nations guarantees continued distribution of petroleum resources from the region regardless of almost inevitable instability within and among producing states.

There are many reasons for having an international rapid deployment force to intervene in failing states both to prevent civil wars and, if necessary, to create a security environment in which diplomats can manage a peaceful restructuring of nations.

Likewise, if climate damage creates massive dislocations due to increased coastal water levels, decreased water supplies, and crop dislocations, as predicted by the Center for Naval Affairs (CNA) studies, the United States should now take leadership to create international institutions and capabilities to anticipate and limit the disruptions and instability these conditions will create.

A strategy of the global commons is anticipatory rather than reactive, appreciating that major disruptions will occur globally so rapidly that reliance on extended time to react is unrealistic. Diplomatic exchanges that took six months to transit between the United States and Europe at our founding, or six weeks a century ago, now take fewer than six seconds.

WITHIN THE context of organizing the global commons as a diplomatic platform and security establishment, the United States will find it necessary to make several unilateral adjustments to its security policy to account for the new realities of the 21st century. The United States is an island nation, not a continental power. As such we will require greater maritime assets, both for increased open-ocean operations as well as for closer-to-shore conflict resolution and rapid-insertion operations.

These conditions require us to rely heavily on sea power and to maintain naval superiority both to protect our long east and west coasts and ports and to establish mobile and flexible presence in a variety of oceans and venues worldwide.

The advantages of a maritime strategy include the ability to shift fleets from ocean to ocean, the flexibility to establish presence in littoral waters and to withdraw over the horizon as circumstances require, the strength to use carrier-based aircraft in long-range attack mode and shorter-range close air support of on-shore operations, the competitive dominance the U.S. has in submarine capability, and the increasing capability of mounting swift insertion operations for rapid response.

As we must be the leading contributor to an international Persian Gulf stabilization force, among other common security interests, we will also find it effective to further consolidate the Joint Operations Command combining the Special Forces, possibly into a new fifth service, to accommodate the increasing burdens of containing localized unconventional conflicts.

To achieve these and other security objectives, however, we must acknowledge the political limits represented by organizing our security operations on an outdated statutory base. The Cold War national security state was established by the National Security Act of 1947 which unified the Army and Navy, and the Marine Corps, under a new Department of Defense and added a new service, the U.S. Air Force. It established the Central Intelligence Agency and created the National Security Council. For 64 years, with some notable exceptions, that legislation has served us well.

But, as Thomas Jefferson famously wrote, to expect each generation to govern itself with the laws and policies of previous generations is to expect a man to wear the coat he wore as a lad. Times change and laws and policies, as well as institutions, must keep pace.

The Cold War ended twenty years ago. NATO has yet to define a 21st century mission. New allies and new rivals are emerging. There are new security threats that do not lend themselves to military response and that cannot be addressed either by old alliances or by the United States alone. The very nature of warfare and the character of conflict are changing.

A new national security statute must apply the 20th century security structures and the experiences derived from them over six decades to the new realities of the 21st century. The very process of updating the legal infrastructure of our national security will require us to reflect on what security means today and how our strategies should be adapted to achieve it.

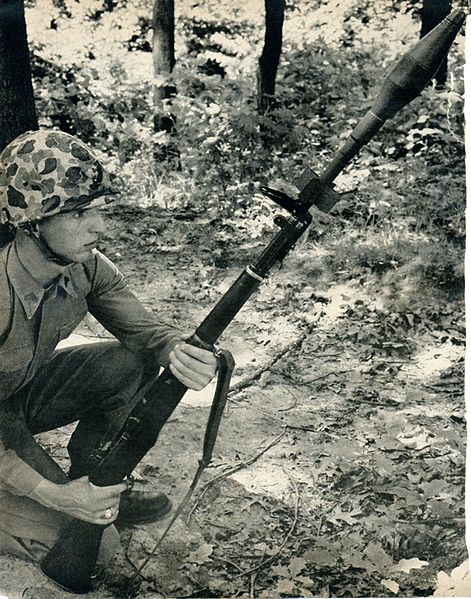

No one argues that our military services are obsolete. We will continue to require land, sea, and air defensive capabilities as long as the Republic lives. Among the early lessons of Afghanistan and Iraq, however, is that 21st century conflict demands Special Forces and small unit capabilities even more than traditional big divisions, large carrier task groups, and long-range strategic bombers. Historic nation-state wars, though always plausible, are declining. Irregular, unconventional warfare involving dispersed terrorist cells, stateless nations, insurgencies, and tribes, clans, and gangs is increasingly prevalent.

Pakistan, whose instability imperils regional and possibly global security, is threatened by indigenous religious fundamentalists. Mexico is endangered by drug cartels that are de facto private armies. Iraq’s and Afghanistan’s ancient tribal and sectarian conflicts will continue for decades. Our massive military superiority cannot resolve these and a number of other conflicts by its sheer size and power.

Extended discussion on future security within the broader security community and public at large should encompass at least these questions: what is the nature of the threats we face; which of these require military response and which do not; are our present and planned force structures configured for new military threats; are weapons procurement programs continuations of traditional Cold War acquisitions or are they focused on future requirements; is the intelligence community properly coordinated and focused on emerging realities; for non-military concerns—such as failed states, radical fundamentalism, pandemics, climate degradation, energy dependence, and resource competition—are new international coalitions needed; are existing alliances adequate to anticipate and respond to these crises or are new ones required; most of all, does our government require new legislative authority to achieve national security under dramatically changing conditions?

The precedents for this kind of thorough-going review are found in the several commissions and studies carried out between the end of World War II (and even before) and the final passage of the National Security Act in 1947. These include the Eberstadt report, planning by George Marshall, hearings in the Senate Military Affairs committee, and a blizzard of behind the scenes maneuvering and power struggles. The creation of the national security state in 1947 was not smooth. Army and Navy traditionalists resisted unification. The structure of the new Defense Department and the powers of its Secretary were repeatedly contested. The makeup and authority of the National Security Council shifted and changed. Opponents of a Central Intelligence Agency foresaw a threat to Constitutional freedom.

Traditional institutional interests, almost always more comfortable with established arrangements and known devils than new arrangements and unknown devils, will predictably resist any review of the sixty-four year old law that underpins the national security state. Today, even to suggest a modernization of our core national security framework is to invite bitter opposition from those who never saw a boat they wanted to rock. Machiavelli was not the first to observe that the status quo has many friends and the ranks of reformers are thin.

The only issue that matters is whether Cold War strategies and structures adequately address present and future realities or whether the realities of a new century demand a fresh look at the institutions and policies, military and non-military, that will be needed to make the nation secure. Jefferson’s 21st century man cannot forever wear the clothes of his younger, 20th century self.