America, Not Duterte, Failed the Philippines

Washington pushed the Philippines away by failing to honor moral, if not legal, obligations to its long-standing ally.

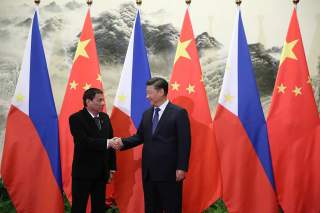

“I HAVE separated from them,” said Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte in October to his Chinese hosts, referring to America. “So I will be dependent on you for a long time.”

Within months of taking office, Duterte had accomplished the inconceivable, reorienting his country away from its only protector, the United States, and toward its only adversary, China. It is China that grabbed Mischief Reef from Manila in the first half of the 1990s and seized Scarborough Shoal in early 2012. The United States is the only nation pledged to defend the territorial integrity of the Philippines.

Some in the Washington policy community, upset with the flagrant display of disloyalty of the Philippine leader, said it was time to end the mutual-defense treaty with Manila. Yet the fundamental issue is not the firebrand Duterte. The issue is Washington. Washington did much to push Duterte away by failing to honor moral, if not legal, obligations to its long-standing ally. The Philippine president did not have to provoke America as he did in October during his trip to Beijing. But his words, though extreme, were nonetheless a predictable outcome of a misguided U.S. policy. It is unlikely that Duterte is spouting off against Washington to get a better deal, playing the Americans off the Chinese and Russians.

His many outbursts against the United States, in fact, look genuine, rooted in a century of Philippine nationalism and mistrust. Duterte was schooled in anti-Americanism from an early age. His grandmother, a Muslim, taught him that the United States was guilty of grave crimes during its colonization of the Philippines. To this day, he refers to the 1906 massacre of the Muslim Moros and believes Washington has not atoned for this particular instance of brutality or, more generally, the torture of Filipinos and the subjugation of his country. To make matters worse, Duterte then learned politics in university in the 1960s from Jose Maria Sison, the founder of the Communist Party of the Philippines. The president now proudly calls himself a leftist.

All these factors mean that America, in Duterte’s eyes, can never do anything right. He still rails about being denied a U.S. visa early last decade. Moreover, he won’t stop talking about what he perceives to be a violation of Philippine sovereignty, the mysterious disappearance of “treasure hunter” Michael Meiring from Davao City in May 2002 after the detonation of a bomb in his hotel room. Duterte, the mayor of that city at the time, believes that Meiring was whisked out of the country by the Central Intelligence Agency.

So not too many Filipinos were taken aback when Duterte slung a homophobic slur at then ambassador Philip Goldberg in August and, by some accounts, directed an equally derogatory comment in the direction of President Barack Obama the following month. As a close aide to Duterte characterized his virulent anti-Americanism, “It’s policy, personal, historical, ideological, et cetera, combined.”

Although Duterte’s views appear warped by prejudice, he nonetheless has good reason to complain about Washington, which despite its mutual-defense pact has not protected his country adequately. Manila has unsuccessfully attempted, since at least the late 1980s, to compel the United States to confirm that the treaty, signed in 1951 and ratified the following year, covers the reefs, rocks, shoals, atolls and islets Manila claims—and China covets—in the West Philippine Sea.

BEIJING, WHICH calls that expanse by its more common name, the South China Sea, claims the same features. Its official maps contain nine, and sometimes ten, dashes forming an area called the “cow’s tongue.” Inside the tongue-shaped area is about 85 percent of that critical body of water, and Beijing claims sovereignty over every feature there. Moreover, official Chinese state media has recently used language directly suggesting that all the waters inside the dashes are sovereign as well. Beijing now has a term for all this: “blue national soil.”

The United States does not take sides on the many South China Sea territorial disputes—China’s claims also conflict with those of Taiwan, Malaysia, Brunei, Indonesia and Vietnam—but Washington does insist on peaceful resolution. Beijing’s actions, however, have been anything but peaceful. For instance, it seized Mischief Reef in a series of acts beginning in 1994. The feature is far closer to the Philippines than other claimants—Hanoi and Taipei as well as Beijing—but Washington did nothing to reverse the Chinese action. American policymakers at the time adopted a serves-them-right attitude because Manila, gripped by one of its bouts of nationalistic fervor, had just ejected the U.S. Navy from its facilities in Subic Bay and the U.S. Air Force from the nearby Clark Air Base.

In early 2012, China moved again. After the Philippines detained Chinese poachers taking endangered coral, giant clams, sea turtles and baby sharks around Scarborough Shoal, Chinese vessels swarmed the feature, which sits only 124 nautical miles from the main Philippine island of Luzon and about 550 nautical miles from China. The shoal—just rocks above the waterline—is strategic because it guards the mouths to Manila and Subic Bays.

China at the strategic speck employed its “cabbage strategy.” By wrapping the shoal “layer by layer like a cabbage” with small vessels, Maj. Gen. Zhang Zhaozhong explained, Beijing could exclude others. In June of that year, Washington brokered an agreement for both sides to withdraw their craft, but only Manila complied. Beijing has been in firm control of the feature since then.

Washington policymakers, despite the seizure, decided to let the matter drop. As Doug Bandow of the Cato Institute suggested, no American president could convince the public to defend “uninhabited rocks of no intrinsic importance.” And as a “senior U.S. military official” told the Washington Post in 2012,

I don’t think that we’d allow the U.S. to get dragged into a conflict over fish or over a rock. Having allies that we have defense treaties with, not allowing them to drag us into a situation over a rock dispute, is something I think we’re pretty all well-aligned on.

In short, the United States did nothing to hold China accountable for its deception. By doing nothing, however, America empowered the most belligerent elements in the Chinese political system by showing everybody else in Beijing that aggression works.

Months after taking control of Scarborough, an emboldened Beijing pressed forward by rapidly stepping up incursions around the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea, claimed by China but under the control of Japan. And Beijing continued to apply pressure in the South China Sea, especially at Second Thomas Shoal, like Scarborough, thought to be part of the Philippines. At Second Thomas, Manila in 1999 grounded the Sierra Madre, a World War II–era hospital ship, to mark the shoal, and left a handful of marines on board. China, once again employing cabbage tactics, used small craft to surround the tiny Philippine garrison. In March 2014, Chinese craft escalated by turning back two of Manila’s resupply vessels, cutting off the troops stationed on the rusting hulk. “For fifteen years we have conducted regular resupply missions and personnel rotation without interference from China,” said Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs spokesman Raul Hernandez at the time.

THERE ARE various theories why Beijing decided to act at that moment. Ernest Bower of the Center for Strategic and International Studies told Reuters that the belligerent Chinese move could have been the result of Beijing’s perception of American weakness in Syria and Ukraine. Yet there is a far more direct explanation. The Chinese knew the United States had remained idle when they grabbed the much-closer Scarborough, even though they had brazenly repudiated the agreement Washington had brokered with themselves and Manila.

In early 2014, Beijing began another provocative initiative by island building—cementing over coral—in the Spratly chain of islands in the southern portion of the South China Sea, creating more than 3,200 acres on and around seven reefs, rocks, shoals and specks. Beijing, most notably, rebuilt Fiery Cross Reef, also claimed by Manila as well as Taipei and Hanoi. The commander of U.S. forces in the Pacific, Adm. Harry Harris, called the newly created features China’s “great wall of sand.”

Moreover, the Chinese have continued provocative conduct. In February 2016, Chinese craft harassed a Philippine navy vessel not far from Half Moon Shoal, just sixty nautical miles south of Palawan, one of the main Philippine islands. And at about the same time, Beijing made an apparent move on uninhabited Jackson Atoll, which also sits off Palawan. Chinese vessels, following the Scarborough and Second Thomas playbooks, had for weeks crowded around the feature, which Beijing calls Wufang Jiao. China’s Foreign Ministry said Chinese craft had worked to free a grounded foreign vessel, a Manila-based fishing boat.

Yet the action was not a temporary effort to aid navigation, as Beijing had claimed. Chinese vessels, both white-hulled (coast guard) and gray-hulled (navy) had swarmed the feature and excluded Filipinos from their traditional fishing grounds. The Philippine Star, a Manila newspaper, called the Chinese ships a “menacing presence.” Eugenio Bito-onon Jr., a mayor in the area, said China’s ships had loitered around the atoll for more than a month. “We can’t enter the area anymore,” an unidentified Philippine fisherman told the Star. Up to five gray and white hulls had been stationed in the area “at any one time.”

“This is very alarming,” Bito-onon told Reuters. To inhabitants of the surrounding area, Beijing’s actions were a threat. “The Chinese are trying to choke us by putting an imaginary checkpoint there,” the mayor said. “It is a clear violation of our right to travel, impeding freedom of navigation.” Freedom of navigation has had no more staunch defender than the United States, but in recent years America has been reluctant to confront China as it attempted to restrict others in its peripheral waters. Washington’s abandonment of Manila was especially evident when an arbitral panel in The Hague handed down its landmark decision in Philippines v. China last July, invalidating the nine-dash line and ruling against China on almost all its positions.

The tribunal held that Mischief Reef and Second Thomas Shoal are within the Philippine exclusive economic zone and on the Philippine continental shelf, and that there was no basis for any claim by Beijing to these two features. With regard to Scarborough, it decided China had violated the traditional fishing rights of Filipino fishermen by exercising control of the shoal. Moreover, the panel ruled that Beijing had operated its vessels at Scarborough so as to create a “serious risk of collision and danger to Philippine ships and personnel,” breaching its international obligations. The Philippines, as a signatory to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), brought the action in 2013, shortly after the Chinese had seized Scarborough. At first, Beijing did not realize the significance of the case filed by Benigno Aquino, Duterte’s immediate predecessor, but China eventually grasped its importance and contested the jurisdiction of the arbitral panel in December of the following year.

Beijing did not accept arbitration delimiting sea boundaries when in 1996 it ratified UNCLOS. Yet its ratification implicitly accepted arbitration of other matters. In October 2015, the arbitration panel asserted jurisdiction over seven of the fifteen claims raised by Manila. In response, China withdrew and did not participate in the substantive phase of the case.

Beijing denounced the 479-page award issued last July. It called the panel a “law-abusing tribunal,” the case a “farce.” The decision “amounts to nothing more than a piece of paper.” “The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China solemnly declares that the award is null and void and has no binding force,” Beijing announced on the day it was issued. “China neither accepts nor recognizes it.” Chinese experts, apparently speaking at the behest of their government, threatened war.

And Duterte, who assumed the presidency two weeks before the decision was handed down, had grounds to be even more upset at America. Secretary of State John Kerry did say China should accept the award, but he spoke without seriousness. He did not pressure Beijing to honor its obligation to accept the ruling, but instead leaned on Manila to bargain with China, backing the Chinese position on starting talks. Kerry’s posture was indefensible. Chinese officials had publicly refused to accept the award as the basis for negotiations. The secretary of state, it was clear, was more intent on avoiding confrontation with a lawless Beijing than upholding centuries of U.S. commitment to defend the global commons.

Duterte, among others, has noticed Washington’s reluctance to protect his beleaguered country. “America did nothing,” he said in October 2015, referring to China’s reclamation activity. “And now that it is completed, they want to patrol the area. For what?” His views on the topic have been nothing if not consistent. America, he maintained at the end of December, should have stopped China “when the first spray of soil was tossed out to the area.” “He feels aligning with our allies against China is not going to benefit the country,” said Jesus Dureza, Duterte’s close friend and cabinet-level peace adviser, describing the president’s views. “The idea is that our allies are not going to go to war for us, so why should we align with them?”

Perfecto Yasay Jr., Duterte’s foreign minister until March, expanded on this theme of betrayal. He noted the “stark reality” that the Philippines cannot defend itself and, in a Facebook post aptly titled “America Has Failed Us,” wrote,

Worse is that our only ally could not give us the assurance that in taking a hard line towards the enforcement of our sovereignty rights under international law, it will promptly come to our defense under our existing military treaty and agreements.

Moreover, Duterte has also made it clear he will not side with America because he believes that in East Asia it has already “lost,” something he made clear during his Beijing trip.

THE UNITED States has by no means lost in any sense of that term, but nuanced, hesitant-looking U.S. policies have created that impression. Washington, throughout the Bush and Obama administrations, inadvertently created the appearance of weakness, and the appearance of weakness is now costing Washington a crucial treaty ally. As Duterte, who obviously prides himself on his strength, makes clear, everyone wants to be on the winning side.

There are, however, several signs that the rift between Manila and Washington can narrow in coming months. First, American policies are moving in a direction more to the liking of the Philippines. The trend began sometime around the beginning of last year. “Early 2016 saw a perceptible uptick in American naval patrols and surveillance activities close to the Scarborough Shoal, which may have contributed to China’s decision to postpone any construction activity on the disputed feature,” Richard Heydarian, a foreign-affairs expert in Manila, told me.

Moreover, the Financial Times reports that last March, President Obama privately warned Chinese ruler Xi Jinping that he would do all he could to prevent the reclamation of Scarborough—“a stark admonition,” as the paper put it—and there are indications Obama repeated the stern words during the G-20 meeting in September in the Chinese city of Hangzhou. American efforts, Manila believes, had some effect. This March, Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana publicly suggested that Washington stopped China at the last minute from cementing over Scarborough. President Trump looks like he will continue to move in his predecessor’s more resolute direction. During his January confirmation hearing, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson stated that China would not be allowed to occupy its reclaimed features in the South China Sea. Moreover, White House spokesman Sean Spicer reiterated Tillerson’s position when he said that the administration would not permit China to grab disputed features. “Under Trump, there is growing confidence that the U.S. will adopt a more robust stance against China,” Heydarian notes about attitudes in the Philippine capital.

The new direction is the product of a realization that, for its own reasons, Washington must stop China from reclaiming and militarizing Scarborough. Militarization would allow the People’s Liberation Army to complete a triangle formed by the airstrip on Woody Island in the Paracels and the three runways on the seven reclaimed islands in the Spratly chain. The interlocking facilities would give Beijing the ability to enforce an air-defense identification zone over the South China Sea, much like the one it declared over the East China Sea in November 2013. Each year, some $5.3 trillion of goods passes on and over the South China Sea—much of it moving to or from the United States—so Washington does not want any other country, especially China, to control the skies over that crucial body of water.

Moreover, there is a sense in Washington that, as Beijing adopts progressively more hostile policies, it must keep China’s navy and air force penned inside what Chinese strategists call the “first island chain.” The Philippine president, who governs a sprawling archipelago in the center of that chain, could give China’s forces easy access out of the South China Sea to the Western Pacific, thereby exposing, among other things, Taiwan and the southern portion of Japan.

Second, nations other than the United States also have an interest in preventing the Philippines from becoming a Chinese dependency. Both South Korea and Japan are critically reliant on tanker shipments from the Middle East crossing the South China Sea. Seoul, now embroiled in a deepening political crisis, has no time for outreach to the Philippines. Tokyo, on the other hand, is working the problem hard. Its prime minister, Shinzo Abe, was the first head of government to pay a call to the country since Duterte took office, traveling to see the Philippine leader at his home in Davao City in January. Abe’s trip followed that of his foreign minister, Fumio Kishida, who was the first foreign minister to go there during Duterte’s administration.

In Duterte’s home, Abe shared a simple breakfast in the kitchen, and the Japanese leader brought gifts. Not only is Tokyo funding a drug-rehabilitation center—thereby helping the Philippine leader with his most important domestic initiative—it is also pledging $8.7 billion in assistance. Money talks loudly in Manila and helps Japan, a staunch U.S. ally, maintain a vital link between Washington and its most troublesome treaty partner. Tokyo, in short, may be the factor keeping Duterte from a final defection to China.

Third, Beijing will also impede Duterte from completing his pivot to China. After all, the Philippines, whether it publicly admits to it or not, is involved in a zero-sum contest with the Chinese state. Beijing now labels its South China Sea claims as “core” and “irrefutable,” and Duterte, although he can make temporary accommodations on issues like fishing rights, cannot compromise sovereignty. If he cedes territory as Beijing demands, he could lose his job. In October, on the eve of the president’s trip to Beijing, Supreme Court Senior Associate Justice Antonio Carpio remarked that Duterte can be impeached if he surrenders Scarborough Shoal. Duterte may say China “has never invaded a piece of my country all these generations”—what he told the Chinese during his October visit—but that is manifestly untrue. And Beijing is ramping up efforts to dominate specks that Filipinos believe are theirs.

Fourth, many in Manila are concerned about Duterte moving the Philippines into the Chinese sphere of influence. Among the pro-U.S. voices is the influential Fidel Ramos, a former president. Ramos, who has counseled Duterte, called his anti-U.S. statements “discombobulating,” and there is general concern in the Philippine capital about anti-Americanism getting out of control. The Philippine military, which has seen fit to change presidents from time to time, is almost uniformly pro-American.

These attitudes are in line with Philippine popular opinion. Poll after poll indicates general support for America, usually around 90 percent. No country, as the last Pew Research Center survey notes, has a more favorable view of the United States than the Philippines. And, predictably, poll after poll indicates that the Philippine public expects Duterte to defend the country’s sovereignty. A recent Pulse Asia survey showed that 84 percent of Filipinos want Duterte to assert rights over South China Sea features, in accordance with the July 12 Hague ruling. In a response to growing public concern, Foreign Minister Yasay revealed in January that he had filed formal protests with Beijing over its activities at Scarborough and in the Spratly chain.

FINALLY, DUTERTE’S ability to reorient Manila’s policy will eventually be undermined by an erosion in his popularity at home. So far, the president enjoys wide support, effectively giving him the latitude to do what he wants. Up to now, his war on drugs has been the centerpiece of his governance and, it appears, the main reason for his big following. The war, marked by extrajudicial executions and state-sponsored murders, has been bloody, claiming over seven thousand lives since his inauguration. During this period, police have been “pro-actively gunning down suspects,” the conclusion Reuters draws from a 97 percent kill rate in police raids.

“Duterte Harry’s” extraordinary campaign has encountered stiff opposition from the Catholic Church and human-rights activists, however, and the president has begun to feel the heat. One of the first signs of trouble for him appeared in late January when Malacanang Palace, the presidential office, had to ask the public to give the “Punisher,” another of Duterte’s nicknames, “an allowance for mistakes.”

Mistakes, like the October kidnapping and killing of a South Korean businessman by antinarcotics officers at the Philippine National Police headquarters, have already slowed his drug war, leading to the late January suspension of the effort. And as more horrible stories pile up, his brutal campaign will surely lose support as police excesses become too blatant—and as his attacks against the Church force the bishops to go on the offensive against him.

Furthermore, another bad sign for Duterte is the reports of growing corruption. The country fell on Transparency International’s Corruption Index last year, and the appearance of venality is something that will affect his legitimacy. Duterte should remember that another tough-guy president, Joseph Estrada, was ousted from power over the issue.

All these domestic trends are crucial because, as Duterte loses altitude, he will inevitably lose the clout to fundamentally change the balance of power in East Asia. Yet President Trump may only have a small window to reverse Manila’s course. In January, Duterte said he was going to Beijing in May to meet Xi Jinping again. That’s about the same time he is expected to travel to Russia.

Why is Duterte intent on traveling to Beijing and Moscow? In September, he said he might “cross the Rubicon” and end the mutual-assistance treaty with the United States in order to ink defense pacts with China and Russia.

Gordon G. Chang is the author of The Coming Collapse of China. Follow him @GordonGChang.

Image: President Rodrigo Duterte and President Xi Jinping shake hands prior to their bilateral meetings at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on October 20, 2016. Wikimedia Commons.