China vs. Japan: Asia's Other Great Game

Beijing and Tokyo will undoubtedly compete long after U.S. foreign policy has evolved.

Asia’s Other Great Game

By Michael Auslin

*** “We confer upon you, therefore, the title ‘Queen of Wa Friendly to Wei’ . . . We expect you, O Queen, to rule your people in peace and to endeavor to be devoted and obedient.”—Letter of Emperor Cao Rui to Japanese empress Himiko in 238 CE, Wei Zhi (History of the Kingdom of Wei, ca. 297 CE) ***

*** “From the emperor of the country where the sun rises to the emperor of the country where the sun sets.”—Letter from Empress Suiko to Emperor Yang of the Sui Dynasty in 607 CE, Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan, 720 CE) ***

THE SPECTER of the world’s two strongest nations competing for power and influence has created a convenient narrative for pundits and observers to claim that Asia’s future, perhaps even the world’s, will be shaped, in ways both large and small, by the United States and China. From economics to political influence and security issues, American and Chinese policies are seen as inherently conflictual, creating an uneasy relationship between Washington and Beijing that affects other nations inside Asia and out.

Yet this scenario often ignores another intra-Asian competition, one that perhaps may have as much influence as that between America and China. For millennia, China and Japan have been locked in a relationship even more mutually dependent, competitive and influential than the much more recent one between Washington and Beijing. Each has sought to dominate, or at least be the most influential in, Asia, and the relations of each with their neighbors has at various points been directly shaped by their rivalry.

There is little question today that the Sino-American competition has the greatest direct impact on Asia, particularly in the security sphere. America’s long-standing alliances, including with Japan, and provision of public security goods, such as freedom of navigation, remain the primary alternative security strategies to Beijing’s policies. In any imagined major-power clash in Asia, the two antagonists are naturally assumed to be China and the United States. Yet it would be a mistake to dismiss the Sino-Japanese rivalry as a simple sideshow. The two Asian nations will undoubtedly compete long after U.S. foreign policy has evolved, and regardless of whether Washington withdraws from Asia, grudgingly accepts Chinese hegemony, or increases its security and political presence. Moreover, Asian nations themselves understand that the Sino-Japanese relationship is Asia’s other great game, and is in many ways, an eternal competition.

CENTURIES BEFORE the writing of Japan’s first historical records, let alone the formation of its first centralized state, envoys from its leading clan appeared at the court of the Han Dynasty and its successors. Representatives of the land of “Wa” were recorded as first arriving in Eastern Han in the year 57 CE, though some accounts place the first encounters between Chinese and Japanese communities as far back as the late second century BCE. Not surprisingly, these earliest references to Sino-Japanese relations are in the context of China’s intervention on the Korean Peninsula, with which ancient Japan had long-standing exchanges. Nor would an observer at the time be shocked by the Wei court’s expectation of deference to China. Perhaps slightly more surprising is the seventh-century attempt by an upstart island nation just beginning to unify to assert not merely equality but superiority over Asia’s most powerful country.

The broad contours of Sino-Japanese relations became clear early on: a competition for influence, an assertion by both of their respective superiority, and an entanglement with Asia’s geopolitical balance. Despite the passage of two millennia, the base of this relationship has changed little. Today, however, a new wrinkle has been added into the equation. Whereas throughout the previous centuries only one of the two nations was powerful, influential or internationally engaged in any given era, today both China and Japan are strong, united, global players, well aware of the other’s strengths and their own weaknesses.

Most American and even Asian observers presume that it is the Sino-American relationship that will determine Asia’s future, if not the globe’s, for the foreseeable future. Yet the competition between China and Japan has been of far longer duration and is of a significance that should not be underestimated. As the United States enters a period of introspection and readjustment in its foreign and security policies after Iraq and Afghanistan, as it continues to struggle to maintain its widespread global commitments and as the full scope of Donald Trump’s desired readjustment of U.S. foreign policy continues to take shape, the eternal competition between Tokyo and Beijing is poised to enter an even more intense period. It is this dynamic that is as likely in its own way to shape Asia in the coming decades as that between Washington and Beijing.

TO MAKE a claim that Asia’s future will be decided between China and Japan may sound fanciful, especially after two decades of extraordinary economic growth that has vaulted China into becoming the world’s largest economy (at least according to purchasing power parity calculations), and a concomitant quarter-century of apparent Japanese economic stagnation. Yet the same claim would have sounded just as unrealistic back in 1980, except in reverse, when Japan had racked up years of double- and high single-digit economic returns while China had barely emerged from the generational disaster of the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution. Just a few decades ago, it was Japan that was predicted to be the global financial power par excellence, countered only by the United States.

For most of history, however, it would have seemed delusional to compare Japan with China. Island powers rarely can compete with cohesive continental states. Once China’s unified empires emerged, starting with the Qin in 221 BCE, Japan was dwarfed by its continental neighbor. Even during its periods of disunity, many of China’s fragmented and competing states were nearly as large, or larger than, all of Japan. Thus, during the half-century of the Three Kingdoms, when Japan’s Queen of Wa paid tribute to Cao Wei, each of the three domains, Wei, Shu and Wu, controlled more territory than Japan’s nascent imperial house. China’s natural sense of superiority was reflected in the very word used for Japan, Wa (倭), which is usually accepted to mean “dwarf people” or possibly “submissive people,” thus fitting Chinese ideology regarding other ethnicities in ancient times. Similarly, Japan’s geographical isolation from the continent meant that the dangerous crossing over the Sea of Japan to Korea was attempted only rarely, and usually only by the most intrepid Buddhist monks and traders. The early Chinese chronicles repeatedly introduced Japan as being a land “in the middle of the ocean,” emphasizing its isolation and difference from the continent. Long periods of Japanese political isolation, such as during the Heian (794–1185) or Edo (1603–1868) periods also meant that Japan was largely outside the mainstream, such as it was, of Asian historical development for centuries at a time.

The dawn of the modern world turned upside down the traditional disparity between Japan and China. Indeed, what the Chinese continue to call their “century of humiliation,” from the Opium War of 1839 to the victory of the Chinese Communist Party in 1949, was largely contemporaneous with Japan’s emergence as the world’s first major non-Western power. As the centuries-old Qing dynasty and China’s millennia-old imperial system fell apart, Japan forged itself into a modern nation-state that would inflict military defeats on two of the greatest empires of the day, China itself in 1895 and czarist Russia a decade later. Japan’s catastrophic decision to invade Manchuria in the 1930s and fight both the United States and other European powers resulted in devastation throughout Asia. Yet even as China descended into decades of warlordism following the 1911 Revolution, and then the civil war between Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and Mao Zedong’s Communists, Japan emerged from the vastation of 1945 to become the world’s second-largest economy.

Since 1990, however, the tide has reversed, and China has come to occupy an even more dominant global position than Tokyo could have imagined at the height of its postwar prominence. If international power can crudely be conceived of as a three-legged stool, comprising political influence, economic dynamism and military strength, then Japan only fully developed its economic potential after World War II, and even then lost its position after a few decades. Beijing, meanwhile, has come to dominate international political fora while building the world’s second most powerful military, and becoming the largest trading partner of over one hundred nations around the globe.

Yet in comparative terms, both China and Japan today are wealthy, powerful nations. Despite nearly a generation of economic doldrums, Japan remains the world’s third-largest economy. It also spends roughly $50 billion per year on its military, boasting one of the world’s most advanced and well-trained defense forces. On the continent, with its audacious Belt and Road Initiative, free-trade proposals and growing military reach, China is widely considered the world’s second most powerful nation, after the United States. This rough parity is new in Japan-China relations, and has been perhaps the single greatest, if often unacknowledged, factor in their contemporary relationship. It is also the spur for the intense competition the two are waging in Asia.

COMPETITION BETWEEN countries does not inherently lead to aggression, or even particularly contentious relations. Indeed, looking at Sino-Japanese relations from the vantage point of 2017 may distort just how vexed their ties traditionally have been. For long periods of its history, Japan looked to China as a beacon in a sea of murk—as the most advanced civilization in Asia and as a model for political, economic and sociocultural forms. While at times that admiration was perverted into an attempt to assert equality, if not superiority, as during the Tang era (7–10 c.) or a millennium later, during the rule of the Tokugawa shoguns (17–19 c.), it would be a mistake to assume there was no positive element to the interaction between the two. Similarly, Chinese reformers understood that Japan had achieved success in modernizing its feudal system in the late nineteenth century to a degree that made it, for a while, a model. It was not an accident that the father of the 1911 Chinese Revolution, Sun Yat-sen, spent time in Japan during his exile from China in the first years of the twentieth century. Even after Japan’s brutal invasion and occupation of China during the Pacific War, the 1960s and 1970s saw Japanese politicians such as Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei reach out to China, restore relations and even contemplate a new era of Sino-Japanese relations that would shape Cold War Asia.

Such fragile hopes, not to mention mutual respect, now seem all but inconceivable. For over a decade, Japan and China have been locked into a seemingly intractable downward spiral in relations, marked by suspicion and increasingly tense maneuvering on security, political and economic fronts. Except for the actual Japanese invasions of China in 1894–95 and 1937–45, the history of Japanese-Chinese competition was often as much rhetorical or an intellectual exercise as it was real. The current competition is more direct, even while taking place in an environment of Sino-Japanese economic integration and globalization.

The current atmosphere of Japanese-Chinese dislike and mistrust is marked. A series of public-opinion polls carried out by Genron NPO, a Japanese nonprofit think tank, in 2015–16 revealed the parlous state of relations. Fully 78 percent of Chinese and 71 percent of Japanese polled in 2016 believed relations between their two countries were either bad or relatively bad. Both publics also saw significant increases from 2015 to 2016 in expectations that future Japan-China relations would worsen, from 13.6 percent to 20.5 percent in China and from 6.6 percent to 10.1 percent in Japan. When asked if Sino-Japanese relations posed a potential source of conflict in Asia, 46.3 percent of Japanese responded affirmatively while 71.6 percent of Chinese agreed. Such findings track with other polls, such as a 2016 survey by the Pew Research Center, which found that 86 percent of Japanese and 81 percent of Chinese held unfavorable views of each other.

The reasons for this public distrust reflect, in large part, the outstanding policy disputes between Beijing and Tokyo. The Genron NPO poll found that over 60 percent of Chinese, for example, cited both Japan’s lack of apology and remorse over World War II, and its September 2012 nationalization of the Senkaku Islands, claimed by Beijing as the Diaoyu Islands, for their unfavorable impression of Japan.

Indeed, the history question continues to dog Sino-Japanese relations. China’s leaders have astutely used it as a moral cudgel with which to bash Tokyo. Pew’s polling thus found an overwhelming 77 percent of Chinese claiming that Japan had not yet sufficiently apologized for the war, yet over 50 percent of Japanese believing their country had apologized enough. Controversial visits to Yasukuni Shrine, where eighteen Class A war criminals are enshrined, by current prime minister Shinzo Abe in December 2013 continued a spate of provocations in Chinese eyes that seemed to downplay Japan’s remorse for the war at the very time Abe was pursuing a modest military buildup and challenging China’s claims in the East China Sea. A visit to China in the spring of 2017 revealed no abatement of anti-Japanese portrayals on Chinese television; on any given night, at least a third if not more of prime-time dramas on stations from all of China’s major provinces were about Japan’s invasion of China, given verisimilitude thanks to actors speaking fluent Japanese.

If the Chinese are focused on the past, the Japanese are most concerned about the present and future. In the same polls, nearly 65 percent of Japanese claimed that the ongoing Senkaku Islands dispute accounted for their negative view of China, while over 50 percent cited the “seemingly hegemonic actions of the Chinese” for leaving an unfavorable impression. Overall, 80 percent of Japanese polled by Pew responded that they were either very or somewhat concerned that territorial disputes with China could lead to military conflict, versus 59 percent of Chinese.

These negative impressions and fears for war come despite nearly unprecedented levels of economic interaction. Even with China’s recent economic slowdown, according to the CIA World Factbook, Japan was China’s third-largest trade partner, accounting for 6 percent of its exports and nearly 9 percent of its imports; China was Japan’s largest trade partner, taking 17.5 percent of its exports and providing a full quarter of its imports. Though exact numbers are difficult to ascertain, it has been claimed that Japanese firms directly or indirectly employ as many as ten million Chinese, most of them on the mainland. The neoliberal assumption that greater economic ties raise the threshold for security conflicts is being tested in the Sino-Japanese case, with both proponents and critics of the concept able to claim that so far, their interpretation is correct. Since the downturn in relations during the administration of Junichiro Koizumi, Japanese academics, such as Masaya Inoue, have described the relationship as seirei keinetsu: politically cool, economically hot. That relationship is reflected in another way by the surging number of Chinese tourists to Japan, who totaled nearly 6.4 million in 2016, whereas the China National Tourism Administration claims that nearly 2.5 million Japanese visited China, ranking second after South Korean tourists.

Yet the growing Sino-Japanese economic relationship has not been left unaffected by geopolitical tensions. Chinese protests against Japan over the Senkaku dispute led to steep declines in Japanese foreign direct investment in China during 2013 and 2014, with year-on-year investment dropping by 20 and 50 percent, respectively. These declines were accompanied by a corresponding increase in Japanese investment in Southeast Asia, including in Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore.

Negative attitudes towards China on the part of Japanese business have been mirrored in the political and intellectual sphere. Japanese analysts have been concerned about the long-term implications of China’s growth for years, but such concerns turned into open worry, particularly once China’s economy overtook Japan’s, in 2011. Since the crisis in political relations caused by repeated incidents in the Senkaku Islands starting in 2010, policymakers in Tokyo interpreted Beijing’s actions as flexing newfound national muscle, and they grew frustrated with the United States for its seemingly cavalier attitude towards Chinese assertiveness in the East China Sea. At one international conference in 2016, which I attended, a senior Japanese diplomat harshly criticized Washington and other Asian capitals for countering China’s expansion in Asian waters with nothing but rhetoric, and warned that it might soon be too late to blunt Beijing’s attempts to gain military dominance. “You don’t get it,” he repeated in unusually blunt language, decrying what he (and perhaps his superiors) saw as undue complacency about China’s encroachment throughout Asia. It is not difficult to get the sense that China is seen by some leading thinkers and officials as a near-existential threat to Japan’s freedom of action.

As for Chinese officials, they are all but dismissive of Japan and its future prospects. One leading academic told me that China already has more wealthy citizens than the entire population of Japan, so that there could be no competition between the two; Japan simply can’t keep up, he asserted, so its influence (and ability to oppose China) was doomed to evaporate. Similarly, a visit to one of China’s most influential think tanks revealed an almost monolithically negative view of Japan. Numerous analysts expressed their skepticism about Japan’s intentions in the South China Sea, perhaps revealing a concern for increased Japanese activity in the region. “Japan wants to get out from under the [postwar] U.S. system and end the alliance,” one analyst asserted. Another criticized Tokyo for “playing a disruptive role” in Asia, and for creating a loose alliance against China. Underlying many of these feelings among Chinese elite is a refusal to accept Japan’s legitimacy as a major Asian state, tinged with more than a little fear that Japan is the only Asian nation, along perhaps with India, that can prevent China from reaching certain goals, such as maritime dominance in Asia’s inner seas.

The sense of distrust between China and Japan reveals not only long-standing tensions, but also a window into the insecurities felt by both countries as they contemplate their respective positions in Asia. These insecurities and tensions combine to create the competition that each is waging against the other, even as they maintain extensive economic relations.

INCREASINGLY, CHINESE and Japanese foreign policies in Asia appear to be aimed at countering the influence—or blocking the goals—of each other. This competitive approach is taking place in the context of the deep economic interactions noted above, as well as the surface cordiality of regular diplomatic exchanges. In fact, one of the more direct clashes is taking place over regional trade and investment.

With its head start on economic modernization and postwar political alliance with the United States, Japan helped shape Asia’s nascent economic institutions and agreements. The Manila-based Asian Development Bank (ADB), founded in 1966, has always been led by a Japanese president, working closely with the American-dominated World Bank. The two institutions set most of the standards for lending to sovereign states, including expectations for political reform and broad national development. In addition to the ADB, Japan also expended hundreds of billions of dollars of official development assistance (ODA), starting in 1954. By 2003, it had disbursed $221 billion worth of aid globally, and in 2014, it still budgeted approximately $7 billion of ODA globally; $3.7 billion of this amount was spent in East and South Asia, mostly in Southeast Asia, and particularly in Myanmar. The political scientists Barbara Stallings and Eun Mee Kim have observed that overall, more than 60 percent of Japan’s overseas aid goes to East, South and Central Asia. Japanese assistance has traditionally been targeted for infrastructure development, water supply and sanitation, public health and human-resources development.

In contrast, China’s institutional initiatives and aid assistance traditionally lagged far behind Japan’s, even though it too began providing overseas aid in the 1950s. Scholars have noted that it has been difficult to evaluate China’s development assistance in part because of the overlap with commercial transactions with foreign countries. Moreover, over half of China’s aid goes to sub-Saharan Africa, with only 30 percent going to East, South and Central Asia.

In recent years, Beijing has begun to increase its activity in both spheres, as part of a comprehensive regional foreign policy. Perhaps most notable has been China’s recent attempts to diversify Asia’s regional financial architecture by establishing the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Proposed in 2013, the AIIB formally opened in January 2016 and soon attracted participation from nearly every state, except Japan and the United States. The AIIB explicitly sought to “democratize” the regional lending process, as Beijing had long complained about the rigidity of the ADB’s rules and governance, which gave China under 7 percent of the total voting share, compared to over 15 percent for both Japan and the United States. Ensuring China’s dominant position, Beijing holds 32 percent of AIIB’s shares, with 27.5 percent of the voting power; the next-largest shareholder is India, with just 9 percent of shares and just over 8 percent of the voting power. Compared to the ADB’s asset base of approximately $160 billion and $30 billion in loans, however, the AIIB has a long way to go in reaching a size commensurate with its ambitions. It was initially capitalized at $100 billion, but only $9 billion of the that so far has been paid in—$20 billion is the goal. Given its initially small base, the AIIB disbursed only $1.7 billion in loans its first year, with $2 billion slated for 2017.

For many in Asia the apparent aid and finance rivalry between China and Japan is welcome. Officials from countries that desperately need infrastructure, such as Indonesia, hope that there will be a virtuous cycle in the ADB-AIIB competition, with Japan’s high social and environmental standards helping to improve the quality of China’s loans, and China’s lower-cost structure making projects more affordable. With an estimated need for $26 trillion in infrastructure development by 2030, according to the ADB, the more sources of financing and aid the better, even if Tokyo and Beijing view both financial institutions as tools for larger goals.

Chinese president Xi Jinping has pegged the AIIB to his ambitious, some would say grandiose, Belt and Road Initiative, essentially turning the new bank into an infrastructure-lending facility along with the older China Development Bank and the newer Silk Road Fund. In comparison to Japan, China has focused the majority of its overseas aid on infrastructure, and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) serves as the latest, and largest incarnation of that priority. It is the BRI, also known as the “new Silk Road,” that represents one of the key challenges to Japan’s economic presence in Asia. At the inaugural Belt and Road Forum, held in Beijing in May 2017, Xi pledged $1 trillion of infrastructure investment spanning Eurasia and beyond, essentially attempting to link land- and sea-based trading routes in a new global economic architecture. Copying a page from the ADB, Xi also promised that the BRI would seek to reduce poverty around Asia and the world. Despite widespread suspicion that the amounts ultimately invested in the BRI would be significantly less than promised, Xi’s scheme represents as much a political program as an economic one.

Functioning as a quasi-trade agreement, the BRI also highlights the free trade competition between Tokyo and Beijing. Despite what many consider a timid and sluggish trade policy, Japanese economist Kiyoshi Kojima had actually proposed a “Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific” as far back as 1966, although the idea was not taken seriously until the mid-2000s, by the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum. In 2003, Japan and the ten-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) began negotiating a free-trade agreement, which came into effect in 2008.

Japan’s major free-trade push came with the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which it formally joined in 2013. Linking Japan with the United States and ten other Pacific nations, the TPP would have accounted for nearly 40 percent of global output and fully a quarter of global trade. However, with the United States withdrawing from the TPP in January 2017, the pact’s future has been thrown into doubt. Prime Minister Abe has been loath to renegotiate the pact, given the political capital he spent on getting it passed in spite of agricultural-lobby opposition. For Japan, the TPP still remains the germ of a larger community of interests based on enhanced trade and investment, and adoption of common regulatory schemes.

China has sought over the last decade to catch up with Japan on the trade front, signing its own FTA with ASEAN in 2010, and updating it in 2015, with the goal of reaching two-way trade totaling $1 trillion and investment of $150 billion by 2020. More significantly, China has adopted a 2011 ASEAN initiative, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which would link the ten ASEAN nations with their six dialogue partners: China, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia and New Zealand. Accounting for nearly 40 percent of global output, and linking close to 3.5 billion people, the RCEP increasingly has come to be seen as China’s alternative to TPP. While Japan and Australia in particular have sought to slow final agreement over RCEP, Beijing has been given a huge boost by the Trump administration’s withdrawal from TPP, and the widespread impression that China is now the global economic leader. Tokyo is finding little success in combating such opinion, yet continues to try to offer alternatives to China-dominated economic initiatives. One such approach is to remain engaged in RCEP negotiations, and another is to have the ADB co-fund certain projects with the AIIB. This type of cooperative competition between Japan and China may become the norm in regional economic relations, even as each seeks to maximize its influence in both institutions and with Asian states.

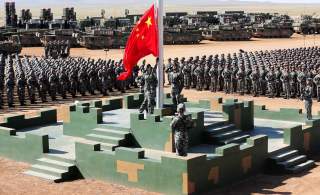

On security matters, there is a far more direct struggle for influence and power in Asia between Beijing and Tokyo. This may sound odd when applied to Japan, which is well-known for its pacifist society and the various restrictions on its military, but the past decade has seen both China and Japan seek to break out of traditional security patterns. Beijing is focused on the United States, which it sees as a major threat to its freedom of action in the Asia-Pacific region. But observers should not dismiss the degree to which Chinese policymakers and analysts worry about Japan, in some cases considering it an even bigger threat than America.

Neither Japan nor China has any real allies in Asia, a fact often overlooked when discussing their regional foreign policies. They dominate, or have the potential to dominate, their smaller neighbors, making it difficult to create bonds of trust. Moreover, memories of each as an imperial power are well remembered in Asia, adding another layer of often-unspoken wariness.

For Japan, this distrust has been abetted by its fraught attempts to deal with the legacy of the Second World War, and the sense on the part of most Asian nations that it has not sufficiently apologized for its wartime aggression and atrocities. Yet Japan’s long-standing pacifist constitution and limited military presence in Asia after 1945 helped tamp down suspicions of its intentions. Since the 1970s, Tokyo has prioritized building ties with Southeast Asia, though until recently those were primarily focused on trade.

Since returning to power in 2012, Prime Minister Abe has moved to increase Japan’s defense spending and expand its security partnerships around the region. After a decade of decline, each of Abe’s defense budgets since 2013 has modestly increased spending, now totaling roughly $50 billion per year. Next, in reforming postwar legal restrictions, such as the ban on arms exports or the ban on collective self-defense, Abe has attempted to offer Japan’s support as a way to blunt some of China’s growing military presence in Asia. Sales of maritime patrol vessels and airplanes to countries including Malaysia, Vietnam and the Philippines are designed to help build up the capabilities of these nations in their territorial disputes with China over the Spratly and Paracel Islands. Similarly, Tokyo hoped to sell Australia its next generation of submarines, as well as provide India with amphibious search and rescue aircraft, though both of these plans ultimately fell through or were put on hold.

Despite such setbacks, Japan has increased its security cooperation with a variety of nations in Asia, including in the South China Sea area. It has formally joined the Indo-U.S. Malabar naval exercises, and sent its largest helicopter carrier to the July 2017 exercise after three months of port visits in Southeast Asia. The Japanese coast guard remains actively engaged throughout the region, and plans to set up a joint maritime safety organization with Southeast Asian coast guards to help them deal not only with piracy and natural disasters, but also to improve their ability to monitor and defend disputed territory in the South China Sea. Most recently, Foreign Minister Taro Kono announced a $500 million maritime security initiative for Southeast Asia, designed to help build capacity among nations in the world’s most congested waterways.

If Tokyo has attempted to build bridges to Asian nations in a cooperative gamble, Beijing has constructed artificial islands in an attempt to be recognized as the dominant Asian security power. China faces a more complicated security equation in Asia than Japan, given its assertive claims in the East and South China Seas, and its territorial disputes with many of its neighbors, including larger nations such as India. The dramatic growth of China’s military over the past two decades has resulted not merely in a more capable navy and air force but in policies designed to defend and even extend its claims. The high-profile land reclamation and construction of bases in the Spratly Island chain exemplify Beijing’s decision to assert its various claims and back them up with a military presence that dwarfs those of other contestant nations in the South China Sea. Similarly, the increase in Chinese maritime exercises in areas far from its claimed territory, such as the James Shoal, near Malaysia, or in the Indian Ocean, has worried nations that see Beijing’s increasing capabilities as a potential threat.

China has, of course, attempted to assuage these concerns through maritime diplomacy, such as engaging in an ongoing set of negotiations with ASEAN nations over a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea, or conducting joint exercises with Malaysia. Yet repeated acts of intimidation, or direct warnings to Asian nations, have blunted any goodwill, forcing smaller states to consider how far to acquiesce in China’s expansionist activities. Adding to the region’s unease was Beijing’s flat rejection of The Hague’s Permanent Court of Arbitration’s ruling against Beijing’s South China Sea claims. Unlike Japan, moreover, China has not sought to win friends by providing defensive equipment; the bulk of China’s military sales in Asia goes to North Korea, Bangladesh and Burma, forging a loose grouping, along with Pakistan (the largest recipient of Chinese arms transfers), that is isolated from those nations cooperating with both Japan and the United States.

China’s approach, a combination of realpolitik and limited machtpolitik, is more likely to secure its goals, at least in the short run, if not longer. Smaller nations are under no illusions that they can successfully resist China’s encroachments; what they hope is either for a natural moderation of Beijing’s behavior or an overreach that will allow communal pressure to influence Chinese decisionmaking. In this calculation, Japan appears primarily as a spoiler. While Tokyo is able to protect its own territories in the East China Sea, it knows that its power in the region is limited. This mandates not only a continuing, if enhanced, alliance relationship with the United States, but also an approach that helps complicate Beijing’s decisionmaking, such as by providing defensive equipment to Southeast Asian nations. Tokyo understands that it can potentially help disrupt, but not deter, Chinese expansion in Asia. Put differently, Asia is faced with competing security strategies from its two most powerful nations: Japan seeks to be loved; China, feared.

A DEEPER manifestation of Sino-Japanese rivalry is the model for national development that each implicitly offers for Asia. It’s not that Beijing expects governments around the Pacific to adopt communism or that Tokyo looks to help install parliamentary democracy. Rather, it is a more fundamental question of how each state is viewed by its neighbors and how much influence each state may have in the region thanks to perceptions of its national strength, governmental effectiveness, social dynamism and opportunities provided by its system.

It should be acknowledged that this is an extremely subjective approach, and the evidence for determining which of the two countries is more influential will more likely be anecdotal, inferential and indirect than explicitly discoverable. Nor is this question of serving as a model the same as the ubiquitous concept of soft power. Soft power is usually defined as an element of national power and, more specifically, the attractiveness of a particular system in creating the conditions through which that state can achieve policy goals. While both Beijing and Tokyo are undoubtedly interested in advancing their state interests, that is a question distinct from how each is viewed and the benefits from the policies they pursue.

Long gone are the days when a Mahathir Mohamad could declare Japan a role model for Malaysia, and when even China considered Japan’s modernization model a paradigm. Tokyo’s hopes to leverage its economic ties with Southeast Asia, the so-called “Flying Geese” model, into broader political influence was derailed by China’s rise in the 1990s. With Beijing being the largest trading partner for all Asian states, it occupies a central position. Yet Sino-Asian relations have remained largely transactional, due both to lingering concerns over Beijing’s assertiveness and fears of being economically overwhelmed. From a short-term perspective, China may appear more influential thanks to its economic power, but that too has translated only fitfully into political gains. Nor has there been an increase in Asian nations attempting to mimic China’s political model.

Instead, both Tokyo and Beijing continue to jockey for position and influence. Each treats with largely the same set of Asian actors, thus offering what Asians consider an almost market-based competition, in which smaller states are able to drive better deals than they would if dealing with either power alone. Moreover, both China and Japan base their policies in part on their perceptions of U.S. policy in Asia. Japan’s alliance with the United States serves in essence to merge Tokyo and Washington into one bloc versus Beijing, while also creating an underlying uncertainty as to American intentions. Japanese concern over the credibility of American promises to remain engaged in the Asia-Pacific drives Tokyo’s military modernization plans, in part to be a more effective partner and in part to avoid overdependence. At the same time, uncertainty over America’s long-term policy enhances Japan’s desire to deepen relations and cooperation with India, Vietnam and other nations that share its worries about China’s growing military strength. Similarly, Beijing’s response to the Obama administration’s involvement in the South China Sea territorial disputes was a program of land reclamation and base building in the Spratly Islands. The same could be said for China’s financial and free-trade initiatives, which are designed at least in part to blunt TPP, which was championed though not started by Washington, or the continued influence of the World Bank in regional lending.

From a mere material perspective, Japan should come off worse in any direct competition between the two nations. Its economic glory days are far behind it, and it never successfully translated its still comparatively powerful economy into political influence. Perceptions of its sclerotic political system add to the sense that Japan will likely never again regain the dynamism it showed in the postwar decades.

Yet as a stable democracy, with a largely content, highly educated, healthy population, Japan is still regarded as the benchmark for many Asian nations. Having long ago tackled its pollution problem, and with a low crime rate, Japan offers an attractive model for developing societies. Its benign international policies and minimal overseas military operations, combined with its generous foreign aid, make Japan the most admired country in Asia, according to a 2015 Pew Research Center poll—71 percent of respondents voiced a favorable view. China garnered only a 57 percent approval rating, with fully one-third of respondents having a negative view.

But current perception and likability benefit Japan only so much. When Genron NPO, the Japanese polling company, asked in 2016 if Japan would increase its influence in Asia by 2026, only 11.6 percent of Chinese and 23 percent of South Koreans answered in the affirmative; perhaps surprisingly, only 28.5 percent of Japanese themselves thought so. When Genron asked the same question about China in 2015, fully 82.5 percent of Chinese, 80 percent of South Koreans and 60 percent of Japanese expected China’s influence in Asia to increase by 2025. Two decades of Chinese economic growth and Japanese economic stagnation undoubtedly are the causes of such findings, but China’s recent political overtures under Xi Jinping likely play some role.

Despite scoring lower than Japan in regional opinion polls, China has ridden a wave of anticipation that its ultimate strength will make it the most dominant nation in Asia, if not the world. This has made it easier to attract cooperation or wary neutrality from Asian nations. The AIIB is just one example of Asian nations flocking to a Chinese proposal; the BRI is another. Beijing has used its influence in negative ways, as well, for example by pressuring Southeast Asian nations such as Cambodia or Laos to oppose stronger criticisms of China’s territorial claims in joint ASEAN communiqués.

At times, China’s very dominance has worked against it, and Japan has taken advantage of the region’s unease at China’s power. When ASEAN nations proposed what would become the East Asia Summit in the early 2000s, with the participation of China, Japan and South Korea, Tokyo successfully lobbied with Singapore for Australia, India and New Zealand to be included as full members. This inclusion of an additional three democratic nations was designed to blunt China’s influence over what was expected to become the largest pan-Asian multilateral initiative, and was decried by Chinese media for doing so.

Neither Japan nor China has succeeded in establishing a dominant position as the undisputed great power of Asia. Southeast Asian nations above all want to avoid being drawn into a Sino-Japanese—or, much the same thing, Sino-U.S./Japan—political and security dispute. The scholars Bhubhindar Singh, Sarah Teo and Benjamin Ho have argued that, in recent years, ASEAN nations have focused more on the U.S.-China relationship, since it is the United States that has Southeast Asian allies and has inserted itself into the South China Seas dispute. Yet all also consider Sino-Japanese ties to be of critical importance for Asian stability in the short and long term. While this particular concern is largely centered on security issues, and less on the larger questions of national models, when attention has turned to national development, the focus on China and Japan becomes even clearer. None dismiss the continuing importance of the United States to Asia’s short- and medium-term future, but awareness of the long history of Sino-Japanese relations and competition is a primary element of the larger regional perception of power, leadership and threat that will shape Asia in the coming decades.

It is a truism, though not unhelpful, to observe that neither Japan nor China can leave Asia. They are stuck with each other and with their neighbors, and each has an intense relationship with the United States. Japan and China’s economic ties are likely to deepen in future years, even as both look for alternative opportunities as well as seek to structure Asian trade and economic relations in ways most beneficial to their own interests. There will undoubtedly be periods of greater political cooperation between Beijing and Tokyo, along with the minimal quotidian diplomatic niceties. There will continue to be grassroots exchange—at the very least, unorganized exchange through millions of tourists.

Their histories and civilizational achievements, however, all but assure that they will remain the two most powerful Asian nations, and that implies an ongoing competition. Whether Japan remains allied to the United States or not, or whether China successfully forges a pan-Asian Belt and Road community, the two will continue to try to shape the Asian political, economic and security environment. With a United States that continues to be challenged by its global commitments and interests, thereby leading to periods of relative lassitude in Asia, China and Japan will stay bound in a complex, often tense and competitive relationship that is Asia’s eternal great game.

Michael Auslin is the Williams-Griffis Fellow in Contemporary Asia at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. This essay was written while he was a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute.