Do Republicans Really Want Tax Cuts?

The coming debate over tax cuts will be a debate about the rich in American society.

The coming debate over tax cuts will be a debate about the rich. “Middle-class tax cut” may be the Washington mantra, but the reality is that any broad-based reduction in personal income taxes, under the current tax code, would redound primarily to the benefit of the wealthy. As the latest IRS data reveals, the top 1 percent of earners pay over 39 percent of personal income tax revenues, while the top 5 percent pay 60 percent; the bottom 50 percent, meanwhile, contribute less than 3 percent of federal income taxes.

This poses a dilemma for the Trump administration and House leadership: Will the new, more populist base of the GOP ultimately support their tax agenda?

The inspiration behind the GOP’s tax plan is Reaganomics. From 70 percent on the eve of Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980, the highest income tax bracket fell to 28 percent after the Tax Reform Act of 1986. The economic dynamism that followed over the next two decades instilled in the Republican policy elite an enduring lesson: Tax cuts are not only politically feasible, they are the key to unlocking growth and innovation.

Particularly vindicated were supply-side economists, who emerged from the academic fringe and sold the Reagan administration on “across-the-board” tax relief. It was a radical move for the time—one that GOP Majority Leader Howard Baker likened to a “riverboat gamble.”

Gamble or not, tax reform paid off. As the country, in January 2000, marked its longest economic expansion in history, supply-side economists Lawrence Kudlow and Stephen Moore could credit marginal rate tax cuts for “unleash[ing] a great wave of entrepreneurial-technological innovation that transformed and restructured the economy.” Supply-siders were encouraged again in 2003 when the Bush administration pushed through upper income tax cuts. As Arthur Laffer and Moore noted in their 2008 book The End of Prosperity, the Bush tax cuts produced within four years 150,000 new jobs per month, $6 trillion of household wealth and a 95 percent increase in the number of millionaires.

So even in a populist moment, supply-side insights carried the day as Republicans formulated their tax plans heading into the 2016 elections. Trump has turned not only to Laffer, Kudlow and Moore, but also to a cabinet of wealthy executives who, like he, embody the capitalist success that the Reagan and Bush tax cuts fostered. The House leadership, likewise, developed its plan with the explicit intent to “replicate and build upon [Reagan’s] achievement.”

Ultimately, Trump and the House GOP reached similar policy conclusions. Both plans call for a flatter tax code in which the top income tax bracket is reduced from 39.6 to 33 percent and high-income taxpayers enjoy the largest cuts.

Reaganomics’ legacy may legitimate the economic case for upper-income tax cuts. But they leave unanswered the political question that the Republican leadership must consider before pursuing another wave of tax relief: Why, despite seeing the virtues of a low-tax society, have Republican voters tolerated a steady increase in taxes since the late 1980s? Barely three years after the Reagan tax cuts came into effect, Reagan’s Republican successor reneged on his “no new taxes” pledge, hiking the upper income bracket to 31 percent. Republican House Minority leader Newt Gingrich railed against this “supreme act of stupidity,” but the American people were more amenable—even in the immediate aftermath of the tax hike, 77 percent of the country agreed that “upper-income people” were paying “too little” in federal taxes. Republicans took control of Congress in 1994 on a pledge to cut taxes, but the upper income tax rate has never since dropped below 35 percent.

The answer lays in the evolution of the political coalition that made Reagan-era tax reform possible in the first place. Supply-side economists provided the intellectual framework for tax reform, but their ascent is intertwined with the broader realignment of the Republican Party.

As late as the presidential elections of 1976, the political map bore little resemblance to today’s red-blue divide. Regionally, Democrat Jimmy Carter won most of the South and Rust Belt, while Republican Gerald Ford swept the West, including California. As in 1972, there was no gender gap between the two parties; men and women voted in equal proportions for the Republican and Democratic candidates. Ideologically, the parties were a hodgepodge; Sunbelt conservatives and liberal Republicans remained in the GOP tent while Carter built on a New Deal coalition that kept African Americans, labor and evangelicals within the Democratic Party.

Reagan’s victory in 1980, however, rebranded the Republican Party. Through his attacks on the welfare state, Reagan united social and free-market conservatives who agreed, if nothing else, that the federal government had overreached into civil society. Across-the-board tax cuts, last championed by the Kennedy administration, became a unifying Republican strategy to “starve the beast”—to rein in an out-of-control federal government by cutting off its funding stream. The Keynesian consensus was shattered and supply-siders found a political opening to slash taxes on the wealthy.

This new, more ideological Republican Party created partisan fissures across gender, regional and urban/rural lines that define presidential politics to the present day. In every presidential election since 1980, men have voted for Republican presidential candidates at a higher rate than women. The South, mountain West and Great Plains have become Republican regional strongholds while the coasts and urban America have turned blue. And between 1988 and 2012, Democrats flipped America’s wealthiest suburbs, while rural counties shifted Republican by an average of two percentage points each election—trends that continued into 2016.

The outsized role that non-coastal white men have played in in the modern Republican Party has had mixed outcomes for anti-tax conservatives. The reason is that the very information age economy that Reagan-era tax cuts fueled has also undercut the status of white males in the upper echelons of American society. This, accordingly, has diminished the appeal of upper-income tax cuts for a core segment of the Republican Party.

Relative to white Republican men, information age prosperity has benefited three (somewhat overlapping) groups that have drifted towards the Democratic Party since Reagan.

The first is upper class women. The growing female role in the highest-earning professions has accompanied the erosion of patriarchal family structure in the upper class. In 1983, women comprised just over a third of high-paying executive, administrative and managerial occupations. Through the 1990s, however, college-educated women followed career tracks parallel to similarly educated men, experiencing wage growth that not only kept pace with, but perhaps even exceeded, that of their male counterparts. By 2001, women made up nearly half of high-paying occupations, and since the 2008 economic crisis, women have received higher returns than men for college completion. Even in upper-class households that have not followed the national slouch toward single parenthood, “breadwinning mothers” are becoming the norm. In 2011, married mothers who made more than their husbands were disproportionately white, college-educated and from families with median total incomes 29 percent above the national mean for families with children. In typical cases, breadwinning mothers are the wives of white-collar men, who, as Newsweek put it, have been “victimized by corporate downsizings” and face “psychic whiplash” from layoffs.

Second—coastal and urban elites. A tax upheaval that was supposed to undermine the economic clout of the eastern establishment has in fact reinforced it. The top 10 percent of American earners—the 10 percent that pay over 70 percent of personal income taxes—live near cities. The contrast between the northeast and the south is particularly stark. Whereas forty-four of the country’s seventy-five highest-income counties are in the Northeast, seventy-nine percent of the poorest U.S. counties are in the South. States most dependent on federal taxes—those that pay the least in taxes but take far more in benefits—have, since the 1980s, moved into the Republican fold.

The third is “model minorities.” Since the late 1980s, growing competition in institutions like higher education—where zero-sum admissions processes serve as gateways into the elite—is eroding individualistic, meritocratic values in the white upper class. At three of the four southern universities that cracked the U.S. News top twenty, Asians represent over a fifth of the student body—numbers unheard of even in the elite northeast schools of the 1980s. Outlier performance from America’s fastest-growing and highest-earning minority group is triggering a backlash in response to what sociologists call “ethnoracial outgroup threat.” Perceiving Asian achievement as an “impending threat” to their “dominant ethnoracial group position,” University of Miami sociologist Frank Samson found in a 2013 study that commitment to meritocratic principles is waning among whites. These sentiments are conspicuous in the suburbs of the new south like Atlanta, where white flight has persistently followed the arrival of high-tech industries and “too many” tiger moms. Amid a sevenfold increase in the suburban Asian population since the Reagan years, the term “competition” itself, as sociologist Samuel Kye discovered, has become a “racial code for the tensions that develop between whites and Asians when Asians succeed.”

Republican America, in short, has become a place where high-income earners are dwindling, where the base of the party is losing its relative privilege and where identitarian insecurity is replacing an individualistic ethos of achievement. Six decades of research on social comparison theory suggest that relative socioeconomic losses, more so than the promise of macroeconomic gains, are weighing psychologically on Republican voters. This would explain why the Republican base has quietly condoned higher, more progressive taxation since the Reagan Revolution, and why, even after eight years of Obama’s historically high tax increases, more than 60 percent of Americans still believe that the upper-income earners aren’t paying their fair share.

Trump’s “post-ideological” campaign resonated with the white working class, but further alienated from the GOP Americans most personally vested in tax relief. The 2016 presidential election was the first since at least 1956 when the Republican candidate lost college-educated whites. The consequence is a new partisan divide: “high-output” Democrats versus “low-output” Republicans. As Brookings scholars Mark Muro and Sifan Liu observe, the 472 counties that voted for Hillary Clinton collectively produce 64 percent of the country’s GDP. Partly, this is because Asian Americans—after supporting Reagan and George H.W. Bush—unified against Trump.

Trump’s advisors have apparently drawn different conclusions from the election outcome. Vice President–elect Pence claimed at the Heritage Foundation that number of counties Trump won has given him the largest mandate of any Republican since Reagan. Stephen Moore brought a more sober “dose of reality” to congressional Republicans: “Just as Reagan converted the GOP into a conservative party, Trump has converted the GOP into a populist working-class party”—a sea change that could frustrate free-market conservatives.

Either way, selling a post-Reaganite Republican base on tax cuts—and the pro-growth, meritocratic culture they encourage—could be an uphill battle. With looming intra-party fights over infrastructure and Obamacare, Trump and House Republicans might conclude that it’s not worth the effort.

Pratik Chougule is the managing editor of the National Interest.

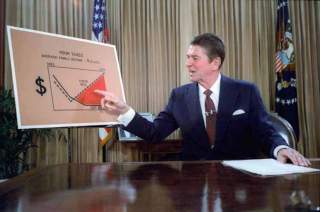

Image: Ronald Reagan gives a televised address from the Oval Office, outlining his plan for Tax Reduction Legislation in July 1981. Wikimedia Commons/Public domain