How to Make U.S. Missile Defenses Stronger

America’s defenses against North Korea can be improved with an "Underlayer."

The United States currently fields a missile defense system of forty-four ground-based interceptors (GBI) designed to engage and destroy a small salvo of ballistic missiles launched at North America by a rogue nation such as North Korea. Such a modest system provides a measure of protection for the homeland, but it’s insufficient to counter the evolving ballistic threat.

To ensure that the United States can deter or defeat ballistic missile attacks, the Department of Defense should support the development of a layered missile defense that incorporates an “underlayer” capability in addition to the primary GBI layer.

An underlayer is a family of shorter-range missile interceptors, including Aegis BMD and Terminal High Altitude Aerial Defense (THAAD), that can track and engage enemy warheads that evaded the higher-altitude ground-based interceptors.

The effectiveness of such shorter-range interceptors has already been proven, both in tests against intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and real-world interceptions against various theater missile threats in Ukraine. So, we know that we can strengthen America’s missile defenses by adding an underlayer to the current GBI architecture.

Background

On November 16, 2020, a U.S. Navy Aegis destroyer launched a Standard Missile-3 Block IIA (SM-3 IIA), which intercepted a target that simulated a North Korean ICBM over the ocean northeast of Hawaii. Originally designed to contribute to missile defenses in Europe and the Western Pacific, this test showed that the SM-3 could contribute to homeland defense.

It has been a long way to get here. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the focus of U.S. missile-defense policy shifted from building defenses against near-peer powers like the Soviet Union to addressing the emerging threat posed by smaller, more unpredictable regional actors—“rogue states”—such as North Korea.

To stay ahead of the North Korean ballistic missile threat, the Obama administration added fourteen GBIs to the thirty fielded by the Bush administration. In doing so, it sought to enhance the Ground-Based Midcourse Defense (GMD) system. This approach coincided with the bipartisan post-Cold War consensus that missile defenses should focus on threats posed by rogue state ballistic missiles. Concerning Russia and China, the United States relied on its nuclear forces (as it did during the Cold War) to deter nuclear threats against the homeland.

The Trump administration altered the acquisition approach to include a fully modernized interceptor called the Next Generation Interceptor (NGI) and planned to add an additional twenty NGI/GBIs to the forty-four deployed currently in Alaska and California. There were plans to fund a significant research and development effort had President Trump won re-election.

Believing that the rogue state missile threat to the homeland will likely expand in numbers and complexity, the Trump Administration and Congress directed the Missile Defense Agency to investigate the feasibility of incorporating regional missile-defense capabilities, such as Aegis SM-3 and THAAD systems, into the homeland missile-defense architecture, which centers on GBIs. While regional missile-defense interceptors cannot compare in size and capability to the GBI, they may be a valuable complement to the missile defense system.

Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin has testified that missile defense against rogue state threats is a “central component” to keeping the homeland safe. In support of this priority, the Biden administration has kept the ball rolling by approving NGI development to proceed with two competitive contractor teams while at the same time upgrading and replacing ground system infrastructure, fire control, and kill vehicle software. These efforts will improve GMD reliability and effectiveness of NGI fielding in 2028.

Though it maintains the current policy of staying ahead of the North Korean ICBM threat, the Biden administration decided not to pursue adding an underlayer to the current U.S. system. But, given the ongoing expansion of North Korean ICBM capabilities and the Russian and North Korean-enabled Iranian ballistic missile programs, the administration should reconsider. Indeed, a recent Congressional strategic posture report found that staying ahead of the North Korean ballistic missile threat “will require additional integrated air and missile defense capabilities beyond the current program of record.”

To understand the outlines of the debate, it’s important to understand 1) the strategic rationale for the underlayer and 2) the potential implications of an underlayer and expanded homeland defense for nuclear arms control and potential arms races.

On balance, staying ahead of the rogue state ballistic missile threat to the homeland is prudent for the following reasons: It is risky and unnecessary to rely solely on deterrence in the face of ICBM threats from North Korea (and potentially Iran, given their advances on a three-stage solid fuel ICBM) when the United States can afford to add a measure of protection against the failure of deterrence, particularly in the form of an effective, layered missile defense that would include an underlayer.

Defense of the homeland has always been a key component of American grand strategy, which relies on allies to maintain a balance of power in vital regions of the world. To reassure allies that we are willing to run risks on their behalf, we must take steps to protect the homeland against North Korean missile threats.

While mindful of the potential for instability with China or Russia, those risks are overstated and manageable.

The Role of the Underlayer in Homeland Missile Defense

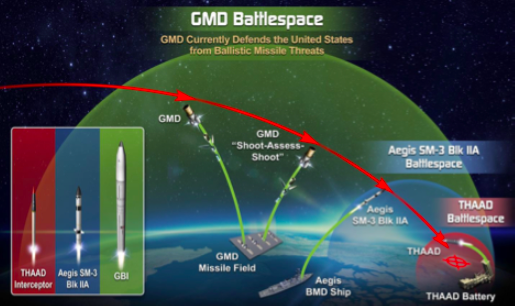

Missile defense works best when interceptor systems are layered. Multiple layers using different defensive technologies and weapons platforms can provide such a defense, also known as a defense-in-depth (see Figure 1). Integrating short, medium, and long-range defense interceptors is not only more efficient and cost-effective but also more likely to intercept its targets.

Currently, the United States relies on the GMD system based in Alaska and California to protect the entire country against a limited adversary attack using a finite number of ICBMs. The GMD system intercepts the attacking warheads while they are outside the atmosphere. As we have noted, two U.S. regional missile-defense systems are under examination for their potential to supplement the GMD system: the Navy’s Aegis SM-3 missile and the Army’s THAAD system.

The SM-3 missile, generally deployed on a naval vessel, is designed to intercept medium- and intermediate-range ballistic missiles when they are outside the atmosphere. The missile is adapted for use as part of Aegis Ashore, a land-based version of the Navy’s Aegis system. There are Aegis Ashore sites in Romania, and there soon will be more in Poland, each of which will carry twenty-four SM-3s.

Aegis BMD ships, which could be surged during a crisis, and Aegis Ashore could provide an additional layer of protection against a limited strike by North Korean or potentially Iranian ICBMs. However, given its smaller size compared to the GBI, the interceptor would not provide coverage for the entire United States. Aegis ashore sites would have to be prioritized to defend against likely targets. Moreover, the SM-3 would not be capable against the more complex Russian and Chinese ballistic missiles armed with penetration aids and decoys, nor would it defend against air and sea-launched cruise missiles.

At least until the end of the Trump administration, the Missile Defense Agency explored the feasibility of including THAAD in the layered defense architecture. Meant to defend forward-deployed forces and military bases against medium and intermediate-range ballistic missile threats, THAAD may have some use against long-range ballistic missiles and perhaps hypersonic weapons in their terminal glide phase. The defensive coverage of THAAD would be smaller than the SM-3, and both are smaller than the reach of the GBI, which can protect the entire nation from its two locations in Alaska and California.

If technically feasible, the underlayer would augment the GMD system against unsophisticated long-range ballistic missile threats from North Korea and potentially other rogue states. The concept is in the exploratory phase. If a future SM-3 test against an ICBM succeeds, the SM-3 and THAAD could be integrated into a layered homeland defense architecture.

Figure 1: Layered Defense Concept (courtesy of the Department of Defense)

The Policy Decision

Opponents claim that ballistic missile defenses for the homeland are unnecessary. They argue that the threat of nuclear retaliation is sufficient to deter North Korea and that ballistic missile defenses upset strategic stability with China and Russia, a challenge far worse than the risk posed by North Korean nuclear missile threats. Let’s look at these arguments.

Is the threat of nuclear retaliation sufficient to deter North Korea?

If nuclear deterrence kept Russian and Chinese leaders from attacking during the Cold War, why shouldn’t the threat of nuclear retaliation likewise deter North Korean leaders?

In the North Korean case, deterring a leader who fears the end of his regime or his life may be very difficult. If Kim Jong-un can strike the homeland with nuclear weapons, he enjoys a significant counter-intervention threat. Any president would have to consider the prospect of a North Korean nuclear strike even in the face of assured retaliation, which may give him pause. A proper defense reduces this North Korean coercive threat.

Far from replacing deterrence for North Korea, a significant missile defense, adapted to changing developments, complements the threat of nuclear retaliation. A North Korean regime considering the use of nuclear weapons for coercion would have to be concerned that such action might not only be fatal because of the potential for a strategic response but also likely to be futile because their missiles would be intercepted.

Finally, the United States relies on nuclear deterrence to check Chinese and Russian nuclear attacks upon the homeland because it has no choice. U.S. homeland missile defenses cannot prevent Russian and Chinese nuclear forces from inflicting damage upon the United States. With respect to North Korea, the United States does have a choice: it can accept vulnerability to North Korean ICBMs and rely on deterrence, or it can modernize and expand its missile-defense capabilities to stay ahead of the threat. It is a matter of priorities, not cost or technical feasibility.

How will Russia and China respond? Will it lead to a breakdown in arms control and a new nuclear arms race?

Despite U.S. government assurances that homeland defenses are meant only for the rogue state threat, Russia and China likely will interpret expanding defenses as a threat to their nuclear retaliatory capability, potentially driving an arms race. While Russia and China bemoan improvements to U.S. homeland defenses, each continues to modernize their own suite of missile defense systems while at the same time expanding nuclear arsenals.

For the foreseeable future, Chinese and Russian offensive nuclear forces would easily outnumber the proposed underlayer. The 2010 New START Treaty permits Russia to field 1,550 warheads on 700 delivery vehicles. China’s intercontinental nuclear capability currently consists of about 104 ICBMs (some with multiple warheads) and seventy-two submarine-launched ballistic missiles, and China publicly revealed a new nuclear-capable heavy bomber with the ability to carry air-launched ballistic missiles.

Russia and China have developed a range of technologies (including various types of decoys, chaff, and jamming, among others) to counter U.S. missile defense systems. At the same time, China’s ongoing expansion of its ICBM fields and the expansion of its submarine ballistic missile force—which the intelligence community believes will reach parity with the U.S. arsenal by the 2030s—underscores the point that such an underlayer will not impact China and Russia’s ability to hold the American homeland at risk.

Given the limited number of SM-3 and THAAD missiles, as well as the interceptors’ technological limitations against Russian and Chinese missiles, these capabilities will not upset strategic stability for the foreseeable future, if ever. As President Vladimir Putin noted, by the end of 2023, 90 percent of Russia’s nuclear forces will be modernized and, in his words, “capable of confidently overcoming existing and even projected missile-defense systems.”

Historical experience shows that missile defense and nuclear arms control are not incompatible. For example, even though the United States has been pursuing missile defenses seriously since the mid-1980s, Russia and the United States have together drawn down their nuclear forces by some 85 percent from Cold War highs. If Russian leaders were seriously alarmed about U.S. missile defenses, they would not have agreed to these reductions.

Some have suggested that Russia’s “novel” nuclear systems (e.g., nuclear-powered cruise missiles, long-range nuclear undersea torpedo, and hypersonic glide warheads) are a response to U.S. missile-defense plans. But according to Rose Gottemoeller, former New START chief negotiator, Putin “is after nuclear weapons for another reason—to show that Russia is still a great power to be reckoned with. These exotic systems have more of a political function than a strategic or security one.”

Recommendations

It would clearly be wise to strengthen our limited missile defenses in the homeland by exploring the utility and feasibility of an underlayer. Specifically:

The MDA should conduct an additional SM-3 test against an ICBM target. Such a test would give greater confidence in the utility of SM-3 defenses against ICBM threats and is a requisite first step to better understanding the viability of an underlayer.

The MDA should explore the utility of Aegis ashore and THAAD against North Korean ICBM threats. A full exploration of the utility of the underlayer, including deep technical analysis, is required if the United States wants to strengthen its defenses. In particular, the technical feasibility of these systems’ ability to successfully engage ICBMs is required. This is the first step in exploring an underlayer.

The Department of Defense should explore the requisite operations concepts and plans for an underlayer. NORTHCOM, in conjunction with the U.S. Navy, should ensure that plans and procedures are in place to employ existing Aegis BMD ships armed with the SM-3 IIA missile in an emergency, should North Korean ICBMs threaten the United States during a crisis or conflict. Increasing production of the SM-3 IIA missile would augment this capability over the next few years.

The department should also identify costs associated with fielding a limited number of Aegis ashore and THAAD batteries in critical locations within the homeland. In a fiscally constrained environment, cost must be addressed. Identifying required costs associated with a prioritized underlayer against key targets is a necessary step to an ultimate decision on whether to field an underlayer.

Conclusion

In the final analysis, any administration must weigh the strategic benefits of defending the homeland against rogue missile threats alongside the potential consequences for our relationship with Russia and China. U.S. missile defense, including the underlayer, is a crucial enabler of U.S. national security strategy, and the potential downsides with Russia and China are overstated.

Defense of the American people against rogue nation nuclear threats should be an obvious priority for policymakers. Less appreciated is that the perception of such protection is essential for a U.S. strategy that ultimately relies on the support of allies. Allies, in turn, count on the United States to run risks on their behalf. If the United States is unwilling to take the steps necessary to defend itself against a country such as North Korea, allies could conclude that Washington may think twice before coming to their assistance in time of need. Missile defense improves America’s freedom of action to protect its allies and global interests.

Russian and Chinese own investments in missile defense belie their criticism of American missile defense systems. Whatever concerns they may hold about our future capabilities, U.S. missile defense plans have not stood in the way of drastic nuclear arms control reductions between Russia and the United States.

Policymakers simply cannot give Russia or China a veto over the protection of the United States against rogue state threats. Far from upsetting strategic stability with Russia and China, improved and expanded homeland defenses, including a potential underlayer, will contribute to collective alliance efforts to meet the challenges posed by rogue actors armed with ICBMs.

Robert Soofer is a senior fellow in the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. He served as deputy assistant secretary of defense for nuclear and missile defense policy from April 2017 to January 2021.

Image Credit: Creative Commons.