Semiconductor Shortfall: America Is Willingly Ceding The Technology Race To Asia

Semiconductor manufacturer Intel’s latest quarterly corporate report ominously noted some serious potential technological vulnerabilities capable of undermining America’s prosperity as well as its national security.

ONE OF the leading features, and weakness[es], of globalist U.S. foreign policy has been the tendency to look mainly to foreign policy to solve problems that domestic policy could likely handle better. That’s because all else equal, conditions at home are much easier to change and control than conditions overseas. Even an avowed non-globalist like President Donald Trump has sometimes been guilty of this.

To solve its energy shortage problem, the United States has long sought to stabilize the Middle East rather than develop alternative fossil fuels or green energy sources. To eradicate, or at least reduce, jihadist terrorism, administrations from both parties mired the nation in costly and protracted foreign wars rather than secure the homeland. And many presidents have fought “wars on drugs” in Latin America and other regions more energetically than they’ve attacked the social and economic ills that fuels domestic narcotics use. The wisdom and track record of these strategies has been unimpressive at best.

NOW, NEWS from an unexpected source could kick off another misguided and potentially even dangerous foreign policy-heavy effort to solve a mainly domestic problem. Semiconductor manufacturer Intel’s latest quarterly corporate report ominously noted some serious potential technological vulnerabilities capable of undermining America’s prosperity as well as its national security.

Intel, of course, is America’s largest producer of semiconductors, and one of the world’s biggest microchip manufacturers. In fact, it’s the only major U.S.-owned producer that still manufactures state-of-the-art logic chips domestically—or at least is still trying to. This capability matters decisively for national technological competitiveness because these are the products whose current capabilities and vast potential drive the so-called process innovation that enables the entire microelectronics industry to create faster, more powerful products. Most of the rest of the semiconductor sector—both in the United States and elsewhere in the world—has transitioned to a so-called “fabless” business model, in which companies develop and design semiconductors while letting contract manufactures handle the challenge of building and operating ever more expensive multi-billion-dollar fabrication facilities (or “fabs” for short).

Semiconductors, therefore, (a) play a central role in making information technology hardware and enabling it to use all the software developed for these devices—including the networking gear that houses the Internet; and (b) are the keys to creating new and vastly better generations of civilian machinery and equipment throughout industry—along with state-of-the-art weapons systems.

It’s easy to understand then why alarm bells have gone off on Wall Street and in the American national security community: Intel not only announced that it had bungled its effort to mass manufacture a new family of chips incorporating the latest generation of performance-improving technology, but raised the prospect of exiting semiconductor manufacturing altogether. Worse, this was Intel’s second straight failure to introduce such next-generation processors. In an industry where product cycles keep getting shorter, such a setback can significantly magnify the longer-term cost of a company lagging behind technologically.

The news so far has been more disheartening for investors though than for the national security community. The former fear Intel’s possible abandonment of the core competence that led to its long-time success. The latter, on the other hand, understand that the U.S. economy and military could still enjoy access to semiconductors incorporating world-class knowhow even if Intel went all-in on fabless-ness. After all, the two other companies with leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing tech are from Taiwan (Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, or TSMC) and South Korea (Samsung). Also comforting is the fact that even many advanced U.S. weapons systems aren’t exactly brand new, and therefore use older chips. Moreover, many of these semiconductors are custom-tailored for military use and, therefore, the smaller domestic producers that still turn them out seem capable of handling order volume.

BUT ALTHOUGH both Asian manufacturing powers are U.S. allies, their location—right on the periphery of China, whose own growing tech prowess is widely considered the premier threat to American security as well as prosperity—looms as an Achilles’ heel. As for legacy technology, America will become increasingly hard-pressed to use it to handle challenges in artificial intelligence, networking, cybersecurity, and the like that will continue to increasingly dominate military operations against foes ranging from peer competitors to non-state actors, along with the anti-hacking efforts of civilian government agencies, businesses, and other institutions.

At this point, worries about the United States responding mainly through bolstering its military presence in East Asia and strengthening its alliance relationships look premature. Both foreign policy and domestic-oriented measures to cope with semiconductor manufacturing shortcomings have been implemented and are being discussed.

The Trump administration has boosted America’s diplomatic support for Taiwan and approved the first sale of new U.S. jet fighters to the island since 1992. Washington has also recently announced a modest increase in the U.S. troop presence in East Asia and has stepped up some anti-Beijing muscle-flexing in the Taiwan Straits and the South China Sea. Yes, the president has also been haggling in public with both Japan and South Korea about the costs of hosting their respective U.S. military bases, thereby inevitably raising questions about America’s military commitment—at least as long as Trump remains in office. But so far, his pro-engagement actions outweigh these words.

Meanwhile, even before Intel’s announcement, a strong, bipartisan consensus had been developing that the United States needs to get serious about growing domestic semiconductor manufacturing—and much of the industry claims to be on board. Naturally, chip companies (including foreign-owned firms operating state-side) have been calling for and anticipating sizable tax breaks and subsidies aimed at encouraging them to manufacture in America once again. And the Trump administration, along with Congressional Democrats and Republicans, seems determined not to disappoint them.

Washington has already come through for TSMC, as an undisclosed amount of promised incentives helped convince the company to set up a chip fab, albeit a medium-sized one, in Arizona. Moreover, in July, both the House and Senate passed, with strong bipartisan support, similar bills aimed at reinvigorating domestic microchip capabilities in manufacturing and related fields. The three production-related provisions common to both versions: offering refundable tax credits for semiconductor-related manufacturing investments for the next several years; authorizing a $10 billion federal program to match state and local incentives for building advanced semiconductor foundries (as facilities that specialize in manufacturing, not designing, chips are called); and creating a new program at the National Institute of Standards and Technology to support leading-edge semiconductor manufacturing on American soil.

But it remains unclear whether even this balance will hold, regardless of who wins the presidency this November. Among the main—and intertwined—reasons: the semiconductor manufacturing fix in which the United States finds itself is sobering. Even traditionally manufacturing-focused Intel has steadily lost interest in keeping the United States as its production flagship. Like nearly the entire information technology hardware sector, it’s acted as if it could both keep its competitive edge and supercharge profits by recognizing the fabrication even of the most sophisticated goods as scutwork. Better—and far more lucrative for the foreseeable future—to let less advanced foreigners handle the actual manufacturing and instead double down on the research, design, and engineering.

FROM THE standpoint of America’s semiconductor manufacturing capability, the end results speak for themselves. Since 1990, the U.S. share of global semiconductor capacity has been cut by more than half—from 37 percent to 12 percent. According to the American industry’s trade association, some 80 percent of global production now takes place in Asia—principally in Taiwan, South Korea, and Japan.

Explosive growth in Asian production accounts for much of this shift. But so does a slowdown in U.S. output. During the American economic expansion of 2001–2007, U.S. output of computer and electronics products (a broad official category of goods that includes semiconductors) rose in inflation-adjusted terms by a robust 160 percent. But during the longer expansion of 2009–2019, that growth rate had dropped to 73.68 percent—less than half as strong.

Since 2001, the nation’s semiconductor workforce has shrunk by nearly 31 percent as well. It’s tempting to ascribe falling employment entirely to increased productivity, but during the 2001–2007 expansion the productivity of the semiconductor and related sectors by its widest measure improved by 58.53 percent. During the longer expansion that just ended, such productivity growth was only 24.18 percent—again, less than half as strong.

Moreover, a good portion of both the domestic growth slowdown and surging Asian semiconductor production stems from the American-owned industry’s own offshoring of its U.S.-based manufacturing—to the point at which the share of U.S.-owned firms’ production capacity in Asia (including China) is nearly as great (41.7 percent) as the share remaining in the United States (44.3 percent). There are two other notable reasons for this offshoring. First, most of the customers for semiconductor makers the world over are now located in Asia as well. These are the firms that comprise the electronics products manufacturing industry, whose wide array of goods are controlled by various kinds of computer chips. And second, much of the industry’s supply chain is now also found in Asia.

In fact, what’s happened to U.S.-based semiconductor production looks a lot like what Harvard Business School professors Willy Shih and Gary Pisano have described as the loss of an “industrial commons”—a national or regional stock of “R&D know-how, advanced process development and engineering skills, and manufacturing competencies related to a specific technology.” Moreover, as the definition implies, this essential “foundation for innovation and competitiveness” includes world-class suppliers and demanding customers, along with employees (known as “human capital” in modern management parlance) highly adept not only at laboratory work but at factory floor work.

Therefore, when U.S.-based semiconductor companies observe (rightly) that their movement to Asia significantly reflects efforts to benefit from Asian government subsidies and tax breaks that Washington has failed to match, they’re sending a message that they’ve moved from a country that has long seemed pretty blasé about nurturing that industrial commons to lands for which it’s a top priority. And the same can be said about the vast gap between how manufacturing overall has long been valued in East Asia versus its status in the United States—where for decades political leaders, influenced by the economics and finance establishments, came to insist that industrial manufacturing no longer matters. Indeed, as early as 1985, then-President Ronald Reagan declared that “the progression of an economy such as America’s from agriculture to manufacturing to services is a natural change.”

Intel, moreover, has been no exception. As the company’s own records show, the United States’ share of its global manufacturing production has fallen from nearly 70 percent in 2004 to a “majority” in 2019. In 2004, 60 percent of its 85,000 employees worldwide were located in the United States. By 2019, its worldwide headcount had grown to 110,800 but the U.S. share was down to 49 percent.

EVEN SETTING aside the current conventional wisdom in Washington that government can’t pick industrial and technological winners remotely as well as the private sector, the reasons for doubting America’s ability to reinvigorate the semiconductor manufacturing industrial commons are easy to tick off. There’s the sheer complexity of producing defect-free (and therefore profitable) quantities of ever more powerful chips, each of which contains billions of transistors that are ever smaller micro-fractions of a human hair wide and thus able to handle a ballooning number of increasingly challenging tasks. There’s the need to recreate an entire end-to-end supply chain (including customers) as opposed to assuming that the industry can survive as a series of multi-billion-dollar chip fabs existing in relative isolation. There’s the short-term and strategically indifferent focus of America’s current dominant shareholder-oriented form of capitalism. There’s the deep ambivalence about any measures smacking of enduring de-globalization on the part of both by Intel and its fabless counterparts. The former, after all, remains jittery about any U.S. government decisions that might endanger its access to its enormous Chinese customer base. The fabless companies depend heavily on China sales too, and from their individual corporate standpoints, reliance on foreign foundries like those of Taiwan’s TSMC has so far worked out swimmingly.

Further, as suggested by many of these obstacles, there’s the powerful inertia—in the public sector as well as the private, intellectual as well as organizational—behind the globalist view that as long as the U.S. economy can even access products like semiconductors, it doesn’t matter where they’re made—especially when the foreign suppliers are military allies. When this access faces serious enough potential threats, steps like sending another carrier battle group to East Asia-Pacific waters or issuing reassuring boilerplate diplomatic statements could understandably seem preferable to moving manufacturing back home.

In fact, it is precisely because of this inertia and the real obstacles to promoting adequate domestic semiconductor manufacturing that switching from a foreign policy-dominant approach to a domestic policy-based approach won’t happen overnight, even with a whole-of-economy-and-society campaign.

It’s true that Americans can take some comfort from the emergence of ways other than shrinking circuit size to drive semiconductor innovation. With speculation rife that the physical limits of shrinkage possibilities are uncomfortably close, and the cost of progress becoming stratospheric, tinier and tinier transistors might not even be the most promising way to improve semiconductor performance, at least in the medium-term.

For example, packaging entails producing the cases and other products that protect the circuits themselves from corrosion and other forms of physical damage, and through which pass the signals that operate all the devices that use them. Long dismissed as one of the low-tech “back end” phases of chip-making and largely offshored to Asia, players in this segment are now valued for their own potential to boost semiconductor performance while preventing problems like overheating. Intel itself has started to tout its prowess in this and similar fields.

At the same time, circuit shrinkage efforts aren’t going away any time soon. TSMC is aiming to deliver a chip to Apple this fall that is a generation ahead of the device on which Intel has just whiffed. They’ll be powering the first iPhones that use the much-ballyhooed 5G communications technology. The Taiwanese manufacturer has also unveiled plans to produce even more capable processors by 2022, and has begun developing their successors as well.

YET DESPITE the bipartisan support for the microchip bills, and still-mounting bipartisan alarm about China-related threats, legitimate questions can be asked about how enduring and serious Washington’s interest in domestic chip manufacturing will be. After all, the U.S. government has been fretting about American industry’s prospects since the 1980s, but its domestic manufacturing capacity still shrank to a small fraction of the global total. Maintaining U.S. forces in the Asia-Pacific region to deter Chinese political pressure and military aggression will therefore be essential for the foreseeable future. But these units should be recognized as a wasting, and possibly already wasted, asset, as growing Chinese and North Korean nuclear and conventional military power may have already eroded the escalation dominance that for decades bolstered the credibility of American defense guarantees. In essence, these countries are either amply capable of launching nuclear retaliatory attacks on the American homeland (China), or are dangerously close to creating intercontinental delivery systems (North Korea). As a result, the America First approach might not be simply the most efficient route to regain national semiconductor and tech vibrancy. It might also be the safest.

Alan Tonelson is the Founder of RealityChek, a blog on economics and national security, and a columnist for IndustryToday.com. In 2016, he advised both the Trump and Sanders campaigns on international trade issues.

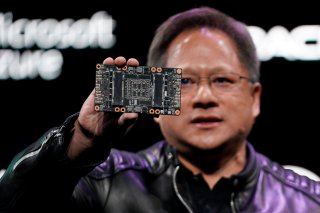

Image: Reuters