Taiwan and Remaking the Case for a League of Democracies

It is critical that democracies work closer together to promote and preserve other democracies in the face of growing influence operations by authoritarian governments.

On September 15, the United States hosted the Ninth Community of Democracies Governing Council Ministerial in Washington, DC. The lead up to the meeting was clouded by growing concerns about the Trump administration’s lack of emphasis on the role of values in U.S. foreign policy. In his remarks, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson went at length to address such doubts at the gathering with senior government officials and civil society leaders from around the world. The Secretary stated unequivocally:

Our shared values translate to more dependable security partners and reliable allies . . . [a]t a time of growing efforts to undermine democracy, it is all the more critical that we work together to bolster and promote this form of governance. So despite the challenges of our day, now is not the time to step back from our democratic commitments. Now is the time to strengthen and sustain them. We cannot become complacent. Rather, we must continue our active advocacy and engagement.

Indeed, it is critical that democracies work closer together to not only promote but also preserve democracies in the face of growing influence operations by authoritarian governments. As the secretary highlighted: “This ministerial could not come at a more critical moment. Across the globe, democratic nations and peoples are under threat.” While the secretary stopped short of calling for a League of Democracies—a coalition of “like-minded nations working together in the cause of peace”—his speech nevertheless clearly underscored the need for democracies to come together and defend against the “threat” to freedom globally. This is a necessary step in the right direction.

Past efforts to create a League of Democracies floundered in the face of disagreements among democracies over the necessity and intent of such a grouping of like-minded countries. There were concerns that the coalition would not be effective as it excluded powerful countries such as China and Russia, and that it could trigger a new Cold War. However, the conditions that made such counterarguments reasonable have changed considerably over the past decade, and the new reality as well as urgency for a coalition of democratic countries are more important than ever. To be sure, there is a clear rise of “authoritarian influencing” or influence operations by authoritarian governments, and a concert of democracies may be the only countermeasure to effectively preserve democracies—and U.S. leadership is key.

Yet, even in past efforts, a critical link was missing. Despite being a democracy, Taiwan is not even a member of the Community of Democracies. Setting aside the technical constraint due to Taiwan’s unique international status, Taipei’s exclusion from that body flies in the face of the values that it purportedly represents. Taiwan’s exclusion, however, begs a more parochial question: how does Taiwan’s democracy serve U.S. policy objectives?

The starting point for that analysis should be with the Taiwan Relations Act. The TRA states, among other things, those goals as:

• to declare that peace and stability in the [Western Pacific] area are in the political, security and economic interests of the United States, and are matters of international concern;

• to consider any effort to determine the future of Taiwan by other than peaceful means, including by boycotts or embargoes, a threat to the peace and security of the Western Pacific area and of grave concern to the United States;

• to maintain the capacity of the United States to resist any resort to force or other forms of coercion that would jeopardize the security, or the social or economic system, of the people on Taiwan.

In pursuit of those objectives, Taiwan’s democracy serve five key roles and functions:

1. Symbolic Value: Taiwan represents a successful case in which U.S. democracy promotion efforts contributed, in part, to bringing about a successful and stable regime transition from authoritarian to a full-fledged democratic system.

2. Domestic Political: Democratization has had a moderating effect on Taiwan’s domestic politics, especially as it relates to cross-Strait relations.

3. Geopolitical: Democracies share common geopolitical interests to work effectively together, namely their people’s desire to preserve their democracies.

4. Cross-Strait Relations: Taiwan’s democracy has a demonstration effect on Hong Kong and the People’s Republic of China. The only hope for China to become democratic is if Taiwan remains free and democratic.

5. Strategic: Taiwan’s experience can help countering the global rise of influence operations by authoritarian countries.

Symbolic Value

Why does it matter that Taiwan is a good symbol for U.S. democracy promotion? There are three main reasons: 1) credibility, 2) as a model for other Asian countries, and 3) strengthening people-to-people ties.

There is a perception among countries that the U.S. government’s promotion of democracy and human rights are entirely self-interested—either it is for resources or to topple unfriendly governments. This perception is usually the result of counterefforts by the ruling elites of those countries, which see democracy promotion as a direct threat on their political rule.

Taiwan’s experience with democratization first as a recipient of the United States’ democracy assistance and as a proponent of democracy elsewhere helps to enhance U.S. credibility among the population of other countries that are the target of U.S. democracy promotion efforts. Greater credibility among the population of the host countries will increase receptivity of the host population to U.S. efforts to support democratic institutions and human rights in those countries.

The United States promoted democracy in Taiwan was motivated in large part by a genuine revulsion by the American public to the plight of Taiwanese people persecuted during the “White Terror,” which refers to the period of political suppression following the February 28 Incident between 1947 to 1987. That is why section two, subsection three of the Taiwan Relations Act states: “The preservation and enhancement of the human rights of all the people on Taiwan are hereby reaffirmed as objectives of the United States.”

Taiwan’s democracy serves as a model for other countries in the region with comparable political and economic conditions to Taiwan during the 1980s that are making a transition to a more open and accountable political system. The country was under martial law from 1949 to 1987. During this period, it also experienced remarkable economic growth. In the 1970s, the political elites began a gradual liberalization of political control that allowed the native population to participate more fully in the political process. This process reached an apex when former President Lee Teng-hui, a native Taiwanese, was anointed as Chiang Ching-kuo’s successor.

While Taiwan’s case is unique in the sense that the political elites faced enormous external political pressure to liberalize, it was also bottom-up inspired transition that make Taiwan’s democracy what it is today. Social movements that emerged in the 1970s that focused on environmental protection, to evolving to include antipollution, consumers, labor, feminist, aborigines, farmers, students’ education and teachers’ rights.

Former Assistant Secretary of State Daniel Russel noted in 2015: “There is a lot that Burma can learn from Taiwan,” he said, adding that the Taiwan example “may serve as an inspiration for many young people in Myanmar.”

There are also the more tangible aspects of deepening people-to-people ties. Shared values and democratic culture can strengthen the people-to-people ties between the United States and Taiwan and therefore contribute to strengthening U.S.-Taiwan relations.

Domestic Political

Democratization in Taiwan is also having a positive effect over the longer term on domestic political developments that serve broader U.S. policy objectives.

First, democratization is having a moderating effect on the country’s politics. In general, different interests represented by political parties are able to compete with each other in the political arena and, over time, this has led to more moderate positions taken by the political parties. This is further illustrated by the measured policies of the current ruling government and also the election of the opposition-party chairperson in May.

Taiwan’s democracy has come a long way from the raucous politics of the 1990s and 2000s. Over time, the driving force in Taiwan’s elections has become less about the primordial issue of independence or unification. Despite some politicians’ efforts to frame issues as such, the fact of the matter is that Taiwan is not on an inevitable path of unification under the People’s Republic of China, nor is it headed in an inseparable path towards independence.

In view of Taiwan’s 2016 presidential and legislative races, coupled with the fact that an overwhelming majority of Taiwanese voters now prefer the “status quo,” the Taiwanese voters will not accept—nor could any political parties commit to—making any dramatic shift to the “status quo.”

Since 2008, there appears to have been a fundamental shift in the Taiwanese electorates’ that all political parties vying for power would have to accept. Democratization in Taiwan and its elections in particular—which some observers saw as a flash point of instability—is becoming a stabilizing force for cross-Strait relations.

Second, a free and hyperactive media environment in Taiwan encourages greater transparency, helps unmask corruption, and disinfects the political process. However, an open media market also makes Taiwan’s democracy susceptible to foreign-influence operations.

Third, public trust in institutions make decisionmaking less dependent on individual decisionmakers and contribute to a more stable political process.

Geopolitical

Some scholars point out that the international system is on the cusp of a power transition: from West to the East, from the United States to China.

This is not the first time in history that a power transition may be occurring. According to Dr. Dan Kliman, however, the current transition may be more dangerous than others in the past due to the nature of the regimes involved. In his book, Fateful Transitions: How Democracies Manage Rising Powers, From the Eve of World War I to China’s Ascendance, Kliman argued that conflict is more likely between democracies and autocratic states in a power transition since the latter masks their intentions and shuts out foreign influences. He notes that it is easier to establish trust between democracies because of shared values and transparent political institutions.

It stands to reason then that the United States will be in a better position to manage a transition—which is not assured—with a rising autocratic China along with other democracies than without. With great foresight to the challenges now facing democracies worldwide, Sen. John McCain issued a clarion call for a “League of Democracies” over a decade ago in 2007. While on the presidential campaign trail, the senator highlighted the purpose of a grouping of democracies best. The premise and conditions that gave rise to his call are more pronounced now than ever before in the post–Cold War era:

We should go further and start bringing democratic peoples and nations from around the world into one common organization, a worldwide League of Democracies . . . like what Theodore Roosevelt envisioned: like-minded nations working together in the cause of peace. The new League of Democracies would form the core of an international order of peace based on freedom. It could act where the UN fails to act, to relieve human suffering in places like Darfur. It could join to fight the AIDS epidemic in sub-Saharan Africa and fashion better policies to confront the crisis of our environment. . . . It could bring concerted pressure to bear on tyrants in Burma or Zimbabwe, with or without Moscow’s and Beijing’s approval. It could unite to impose sanctions on Iran and thwart its nuclear ambitions. . . . This League of Democracies would not supplant the United Nations or other international organizations. It would complement them. But it would be the one organization where the world’s democracies could come together to discuss problems and solutions on the basis of shared principles and a common vision of the future.

Taiwan’s survival after derecognition is in large part attributable to the fact that it became a democracy. When the United States normalized relations with the PRC, there were senior U.S. policymakers who believed that it was only a matter of time—and not a very long time—that Taiwan would collapse into PRC’s embrace. Despite such expectations, Taiwan thrived in the ensuing four decades. The government liberalized from the top down, while an active civil society fervently pushed for political reforms from the bottom up. Taiwan evolved from an authoritarian government to a vibrant democracy. As a result, support for Taiwan grew within the United States. If Taiwan did not become a democracy, it’s far from assured whether it would be as it is today. As the world becomes more globalized, Taiwan’s ability to resist PRC coercion and maintain its social and economic system will depend in more part on its ability to rely on a support network of like-minded countries.

Cross-Strait Relations and Hong Kong

Another positive contribution of Taiwan’s democracy is for its demonstration effect on China and Hong Kong. The only hope for China to become democratic is if Taiwan remains free and democratic. As a Chinese-speaking democracy, Taiwan has a unique role in China’s democratic future. Taiwan’s democracy and what happens in it has a demonstration effect on Hong Kong and the PRC.

Exposure to Taiwan’s democracy give Chinese people a taste of democratic life. Taiwanese political talk shows, which are famous for their no-holds-barred political sparring, are a big hit in China. Moreover, Taiwan’s presidential elections are closely watched by Chinese netizens—albeit tightly controlled. All of this should ostensibly raise expectations for democracy in the PRC.

Strategic

Influence operations by authoritarian governments are on the rise. This was made abundantly clear in the recent U.S. presidential election. But, it is not only Russia that is engaged in such subversive activities but also China.

Such operations involve not just political meddling and propaganda but infiltration of political parties, NGOs, and businesses. Recent events in New Zealand and Australia, and other Western countries, are cases on point.

Taiwan’s long experience in dealing with Chinese political warfare and influence operations could help other countries that now face similar threats by information sharing and raising situational awareness.

While concerns over the Trump administration’s lack of emphasis on values in foreign policy has been a drag on the credibility of his administration’s foreign policy, Secretary Tillerson’s forceful remarks at the Community of Democracies is a step in the right direction. Despite the challenges that bedeviled the start of his administration, President Trump has a historic opportunity when he makes his way to Asia in November to get his foreign policy back on the right track. Against the backdrop of the growing threat of influence operations by authoritarian governments, the United States and her democratic allies should revitalize the League of Democracies and Taiwan must be an integral part of it.

Russell Hsiao is the executive director of the Global Taiwan Institute and chief editor of the Global Taiwan Brief. This article is adapted from remarks delivered at the East Asia Democracy Forum held in New York on September 18, 2017.

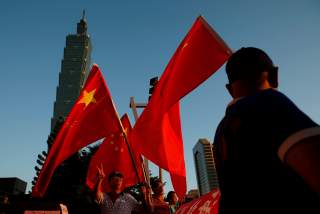

Image: Pro-China supporters hold Chinese national flags in front of landmark building Taipei 101, outside the dinner venue of Sha Hailin, a member of Shanghai’s Communist Party standing committee, in Taipei, Taiwan August 22, 2016. REUTERS/Tyrone Siu

RECOMMENDED:

What a War Between NATO and Russia Would Look Like.

What a War Between America and China Would Look Like.

What a War Between China and Japan Would Look Like.