Technology and Great Power Competition: 5 Top Challenges for the Next Decade

Odds are, regardless of who wins in the 2020 presidential elections, the great-power competition paradigm will prevail into the next administration and beyond. And whoever sits in the Oval Office will have to grapple with the impact of new emerging technologies.

Welcome to the age of great-power competition. Much more than a geopolitical bumper sticker, this label describes the foundation of what has become the free world’s new grand strategy, not just for the United States, but for many of our friends, partners and allies as well.

It is a competition without precedent. One aspect of this new world disorder—advanced technological competition—is particularly noteworthy. It will be infused throughout the struggle, and if Washington wants to win, America will have to do better.

A New World View

Today, the United States sees China, Russia, North Korea, Iran and transnational Islamist terrorism as the chief threats to world stability. That is not just the Trump administration’s view; Bush and Obama had the same list, although they had different strategies for dealing with these threats.

They also had different additional concerns. Bush obsessed about Saddam Hussein. Obama fretted over climate change. Trump is preoccupied with border security. Nevertheless, the fact that three very different presidents from the nation’s two major political parties shared a common threat perception is notable. That hadn’t happened since the end of the Cold War. Further, there is no question that, over the last decade, the United States has seen an emerging bipartisan consensus as to what poses major threats to America’s vital interests around the world.

Admittedly, this opinion is not universal. There is debate. In the U.S. voices on the right and left dissent from the new orthodoxy. Many European allies eschew the notion of dividing the world between friends and enemies. They would prefer to see a European neutral zone and not take sides. In Asia, some powers that share our disdain for China and terrorists are more sanguine about Iran and Russia. So, just as during the Cold War, there is an admixture of both consensus and nonconformity.

Also, let’s grant the term “great powers” is inelegant and imprecise. None of these nations is a truly great power. Russia’s economy is smaller than that of Texas and eight times smaller than China’s. North Korea has the world’s worst economy while Iran’s is only marginally better. Diplomatically, politically, and militarily they are all different. Yet, each in its own way presents a grave destabilizing danger to the parts of the planet where stability is important to American interests.

Granted, none represents an existential menace to the United States. in the manner of the Soviet Union. Moreover, they have but limited interest and capacity when it comes to joining forces against America. Still, collectively they offer a spectrum of global challenges on par with the problems faced during the Cold War. And, since the United States remains a global power with global interests and responsibilities, it is more than appropriate to view them, taken together, as the pacing threats of our time.

Finally, “competition” is definitely the right word to frame what the United States is up against. None of these entities, not even the terrorists, expects to win by fighting big battles with America. Explicitly, the strategy is to “win without fighting”—to find the means, fair and foul, to diminish, undermine and counter American power.

In turn, the United States “wins,” not by fighting wars and fritting away its power and influence trying to police the world, but by outcompeting its enemies. Competing effectively means it’s as important, if not more important, to sustain American strengths and competitive advantages as it is to weaken our adversaries. As long as the United States and its friends, allies and partners retain the capacity to protect their freedom, posterity and security, they will be able to outrun, outlast and overmatch any combination of evildoers looking to bring the country down. That is the core animating action behind a global strategy for prevailing in an age of great-power competition.

Technology as Wild Card

Odds are, regardless of who wins in the 2020 presidential elections, the great-power competition paradigm will prevail into the next administration and beyond. And whoever sits in the Oval Office will have to grapple with the impact of new emerging technologies.

Of course, regimes always face challenges brought by new technologies, be they wheels, bows and arrows, gunpowder, electricity, dynamite, or the Internet. Some technological waves, like the outbreak of the Industrial Revolution and the onslaught of the digital economy, are truly transformative. That’s what we’re looking at now. From quantum computing and artificial intelligence to new advances in the life sciences to a new race in space, the world will have to absorb a tsunami of technological innovation in the decades ahead.

It would be chancy to predict winners and losers in technological innovation. Innovations often take unanticipated paths. The Internet was for universities to share technical data files. E-mail was supposed to be an electronic letter, the World Wide Web—a digital bulletin board. What scientists and engineers put in the front end doesn’t necessarily prescribe the choices of soldiers and consumers at the back end. And who knows who will dominate? A few decades ago, America Online MySpace and Yahoo were supposed to be the big digital players. And, no one knows what the markets will look like. In 2000, there were about 85 million cellphone subscribers in China. Today, there are 1.6 billion.

Yet, there is no question that some kind of big change is coming. The rush of new technologies is bound to affect how national security practitioners try to sustain America’s global competitive strengths. Here are the top five challenges they will face.

#5 Mastering Networking. Modern technology expresses itself through networks, much in the way assembly lines enabled the Industrial Revolution. Creating, empowering, understanding, degrading, disaggregating, and destroying networks is crucial in contemporary competition. That holds true whether the issue is protecting emerging 5G networks or taking down an international global criminal cartel.

Virtually every instrument of national power, from strategic intelligence to implementing sanctions, requires retooling with the people, talents, instruments, data and capabilities to map networks—in the real and digital worlds, often in real-time. Not having an arsenal of network Jedis in this age of great-power competition is like taking on the Sith Lord without a lightsaber. While new technologies empower networks, they also provide tremendous new opportunities to develop capabilities to understand and engage networks.

#4 Protecting Privacy and Liberty. Invariably, the more we mess around with networks and all the information they might hold, transit or share, the more this will raise concerns over individual privacy. It’s imperative to safeguard the personal information of American citizens as well as respecting the privacy of our friends, allies and partners around the world.

Another concern: while the Internet has become a global public square of free speech, that square has been soiled with extremist speech, terrorist activities, child pornographers, scammers and all kinds of malicious activity. Not addressing these issues in a proactive, responsible manner is just asking for trouble. The debilitating disputes we had over the Patriot Act after 9/11 or the donnybrook over NSA’s metadata collection program could pale in comparison to future fights over intrusions into our personal space as governments, friendly and unfriendly, go after great powers.

There is no one-size-fits-all answer to the many issues we’ll squabble over. Trashing free markets is not an acceptable solution. Neither is sacrificing individual rights or putting our security in jeopardy. If our government can’t get ahead of this with the right balance of respect, then transparency, prudence and effectiveness, these problems will only get worse.

#3. Managing Arms Control. Dickering over international rules and constraints will be back, big-time. Nuclear weapons, cyber, autonomous technologies, artificial technology, space, will be among the tech-related topics on the negotiating table. Some will see a renewed arms control effort as the best way to constrain the malicious use of technology.

Unfortunately, many arms control advocates have an almost sycophantic obsession with the process, ignoring the importance of context. Having a deal for the sake of a deal is not necessarily a win-win. In an age of great-power competition, powers will always look to win every possible advantage for themselves in negotiations. And while the theory is that all negotiating parties will then abide by the agreed-upon rules, in practice our adversaries proceed to ignore them.

The Intermediate-Range Forces Treaty collapsed because Putin just decided to cheat. Beijing has made a mockery of the Convention on the Law of Seas, simply ignoring the dictates of the treaty when they proved inconvenient to Chinese interests.

Agreements between like-minded nations may work. Pacts with adversarial powers will only serve if there are strong provisions of transparency and verification—and if they efficaciously address risks. Future arms control negotiations are going to be full-time employment for the U.S. interagency team; they need to stock up with professionals who are up to the task.

#2 Partnering the Public and the Private. Through most of the Cold War, the public sector contributed to the effort far more than the private sector. Security spending accounted for half the federal budget, and Washington spent much more on research and development than did the private sector. Defense and intelligence agencies monopolized the cutting-edge technologies that impacted security competition.

As the song goes, “the times they are a-changin'.” Today, not only does the private sector lead in some of the most crucial tech areas, but many of these companies have a global footprint, doing business in all regions of the world, including China.

The fact is, the United States cannot prevail in great-power competition without cooperative relationships with—and trust and confidence in—the private sector.

Accomplishing this end is no easy task. On the one hand, there will be concerns of corporatism: think of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s warning about the corruptive influence of the Military-Industrial Complex. On the other hand, the tech industry is riddled with an innate prejudice against contributing to American national security, as evidenced by the revolt of Google employees against working with the Defense Department. None of these challenges can mastered by the occasional meetings of CEOs and federal officials. This will require hard thinking, hard work, a lot of integrity, a dose of patriotism and a lot of adults in the room.

#1 Setting Civil/Military Relations. You can take it to the bank: the U.S. military will get sucked into the vortex of all the issues outlined above. And it will have to among those helping to hammer out equitable solutions.

These challenges will add a new layer of strain to those responsible for balancing roles and responsibilities between military and government officials. The model of cleanly dividing military and political policy won’t work—if it ever did. On the other hand, soldiers shouldn’t try to act as politicians and politicians shouldn’t try to play admiral.

What this country will need are military members who understand the political context in which they operate and political leaders who understand the realities of military competition in the era of great powers. This a cadre that can be developed only through a judicious combination of education and experience. It is one of the most crucial professional development challenges of modern times.

A Heritage Foundation vice president, James Jay Carafano directs the think tank’s research program on matters of national security and foreign affairs.

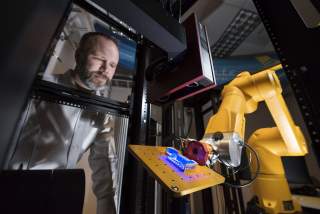

Image: Flickr / Sandia Labs