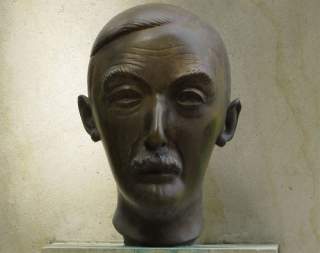

The Mysterious World of Stefan Zweig

The turbulent life of the popular Austrian novelist who escaped the Nazis—but could not escape himself.

George Prochnik, The Impossible Exile: Stefan Zweig at the End of the World (New York: Other Press, 2014), 408 pp., $27.95.

IN JOSEPH Roth’s novel Radetzky March, Count Chojnicki drives district captain Franz von Trotta and his son Carl Joseph, a lieutenant in the Austrian infantry, in a straw-yellow britska to his small hunting lodge in the Galician forest near the border with Ukraine. After pouring glasses of 180 proof, Chojnicki disconcerts his two guests by declaring that the Habsburg Empire is doomed:

With great effort Herr von Trotta asked another question: “I don’t understand! Why shouldn’t the monarchy still exist?” “Of course,” Chojnicki answered, “taken literally, it continues to exist. We still have an army”—the count motioned to the lieutenant—“and officials”—the count pointed to the district captain. “But it is disintegrating. . . . An aged one, whose number is up, endangered by each sniffle, hangs onto his throne simply by the miracle that he can still sit upon it. How much longer, how much longer! This era doesn’t want us any longer! This era wants to create nation-states! No one believes in God. The new religion is nationalism. . . . The monarchy, our monarchy, is based on piety: in the belief that God elected the Habsburgs. . . . Our Emperor is a secular brother of the Pope. . . . The Emperor of Austria-Hungary cannot be abandoned by God. But now God has abandoned him!”

Chojnicki’s lament reflects the profound sense of abandonment that assailed not only Roth, but also his compatriot Stefan Zweig. Both mourned the collapse of the Habsburg monarchy and the loss of the comforting stability it had represented, not least for Jews like themselves. Both became refugees, going into exile years before the Anschluss, or annexation, of Austria by Nazi Germany in March 1938—in a 1933 letter, Roth warned Zweig that it was all over once Hitler had been appointed chancellor by the senescent President Hindenburg. And both ended up destroying themselves—the alcoholic Roth, dependent on handouts from Zweig, perished of delirium tremens in a Paris hospital in 1939 at the age of forty-five; Zweig, together with his young second wife, Lotte, swallowed poison in a little bungalow in 1942 in Petropolis, a lovely mountain resort located near Rio de Janeiro. Unlike Roth, however, Zweig’s literary star dimmed after his death, even though he was one of the most popular authors in the world during the 1930s, an era when books, like the cinema, could command a mass audience.

Now, in his beguiling study The Impossible Exile, George Prochnik examines Zweig’s odyssey. Prochnik, who is the author of In Pursuit of Silence, sets Zweig in the context of literary and social Vienna. It’s very much a life and times rather than a discussion of the old boy’s oeuvre, which was rather vitriolically attacked as “just putrid” by Michael Hofmann in 2010 in the London Review of Books. That his works don’t measure up to Thomas Mann’s or Roth’s almost goes without saying.

But Zweig, a compulsive collector whose possessions included Goethe’s pen and Beethoven’s desk, makes for a fascinating subject (Wes Anderson’s charming new film The Grand Budapest Hotel was inspired by him). Prochnik mines both Zweig’s memoir The World of Yesterday as well as his letters to offer numerous insights. He suggests that Zweig, who was friends with everyone from Richard Strauss to Sigmund Freud, provides an acute lens through which to examine not only the cultural contradictions of the imperial city, but also the plight of the numerous cultural émigrés from Central Europe whom Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels ridiculed as “cadavers on leave.”

Zweig was a pacifist and visionary, an ardent exponent of a pan-European culture. But in contrast to Mann, who could confidently declare, “Where I am there is German culture” and who flourished during his California exile, he became increasingly mentally unmoored as the Third Reich went from success to success. He was constantly searching for a safe harbor—southern France, Paris, London, New York, finally Brazil—only to encounter new and ever more turbulent emotional waters. “I would like to live forgotten on a forgotten place somewhere and never to open more a newspaper,” Zweig told a friend in New York. In losing the narrative thread of his life, Zweig himself, you could even say, ended up becoming the story.

BORN INTO a wealthy Viennese family in 1881, Zweig was cosseted by his mother, whose claustrophobic embrace he came to resent. Both his friends and enemies viewed him as a somewhat protean figure. His dapper dress and ambiguous sexuality, his suave manners and emotional detachment, were of a piece with the glittering sheen of fin de siècle Vienna, where, as the novelist Arthur Schnitzler had one of his characters mordantly announce, “With us indignation is just as insincere as enthusiasm. Only envy and hatred of real talent are genuine here.” As Klaus Mann mused about Zweig, “Only Vienna produced that peculiar style of behavior. French suavity with a touch of German pensiveness and a faint tinge of Oriental eccentricity.”

But that suavity could not mask the virulent anti-Semitism pullulating in the imperial city—as the German historian Brigitte Hamann has shown, Hitler’s mental world was largely formed in Vienna by sinister pan-Germans such as Guido von List and Georg Ritter von Schönerer. The critic Karl Kraus described Vienna as a “laboratory for world destruction.” Its homunculus went on to transform German politics into a kind of mass theater, with himself as the impresario, living out his thwarted artistic ambitions. “Brother Hitler,” as Thomas Mann referred to him, is probably best viewed as a lethal Viennese export who made it big after he left his homeland. Zweig himself wrote in his memoirs that he could not recall when he had first encountered Hitler’s name.

Zweig, who was hardly oblivious to the seamier sides of Austrian society, never sought to suppress his Jewish heritage. Quite the contrary. “What human problem,” he said in 1931, “can be so important as that of the race to which one is born?” Always an extremely facile writer, Zweig began contributing at age nineteen to the Neue Freie Presse, where Theodor Herzl, the father of modern Zionism, served as literary editor. They had much in common: “For all his enviable fluency,” Prochnik writes, “Zweig, like Herzl, viewed literature not as an ultimate task, but as a bridge to some hazy, higher mission on humanity’s behalf.”

Still, Zweig rejected Herzl’s Zionist ideals. To him they were backwards and insular—redolent of nationalism. In a revealing 1917 letter to the philosopher Martin Buber, Zweig explained that he had “never wanted the Jews to become a nation again and thus to lower itself to taking part with the others in the rivalry of reality. I love the Diaspora and affirm it as the meaning of Jewish idealism, as Jewry’s cosmopolitan human mission.” But cosmopolitanism could only take one so far. The scholar Gershom Scholem said that the conviction that intellectuals such as Zweig had of belonging to the German people on purely cultural terms was a “lurid and tragic illusion.”

Time and again, Zweig was confronted with the realities of Nazism that he would probably have preferred to elide. In exile in London in 1935, where he learned that his beloved publisher Insel Verlag had dropped him, Zweig tried to avoid politics. According to Prochnik, he “gave feebly anodyne responses about what a nice, quiet place England was to work in . . . making no mention of the fact that he was fleeing the encroachment of National Socialism, the ascendancy of homegrown Austrian Fascism, and the ever-more-virulent anti-Semitism throughout Central Europe.” Zweig shrank from enmeshing himself in politics. Instead, he wanted to create great art that would serve as a standing refutation of Nazi doctrine. In Prochnik’s view, “Zweig wasn’t suggesting that intellectuals should do nothing, but rather that they got nowhere by simply vilifying their adversaries.”

Zweig’s high point came during an address to the European PEN Club in May 1941 at the Biltmore in New York to hundreds of his fellow émigrés, including Thomas Mann, Andre Maurois, Franz Werfel and Lion Feuchtwanger. In it, Zweig surprised his audience by apologizing for the inhumanity of Nazism:

We writers of the German language feel a secret and tormenting shame because these decrees of oppression are conceived and drafted in the German language, the same language in which we write and think. I feel it is my duty publicly to ask forgiveness of each of you for everything which today is inflicted on your peoples in the name of the German spirit.

This address amounted to a self-reproach for the rise of Nazism. It was as close as Zweig came, or could come, to confronting the moral abyss of Nazism publicly. “Like German culture,” Prochnik writes, “Zweig was a wreck.”

Does Zweig’s detached stance merit criticism? Hannah Arendt, writing in Aufbau, the New York German Jewish newspaper, thought it did. She said that Zweig had romanticized the past in The World of Yesterday. Sounding like Scholem, she said that it was not the world of yesterday but, rather, a gross illusion:

The gilded trellises of this peculiar sanctuary were very thick, depriving the inmates of every view and every insight that could disturb their enjoyment. Not once does Zweig mention the most ominous manifestation of the years after the First World War, which struck his native Austria more violently than any other European country: unemployment.

This is the critique of Zweig as the grand seigneur, oblivious to the dangerous currents swirling beneath that would hurl him and his brethren into the cataract of history. According to Prochnik, “Zweig set himself up for such attacks by virtue of having been, undeniably, an awfully wealthy man who preferred the company of established great artists and ardent young male poets to just about anyone.”

Prochnik goes on to defend Zweig. He observes that Zweig does cite unemployment in his memoirs as a reason for Hitler’s rise. Zweig, together with his first wife Friderike, had established education courses for workers living in Salzburg. His solution to the woes of the time was education. According to Prochnik, Zweig believed that “school curricula might be turned away from their focus on political and military history, toward a program of cultural enlightenment that would elucidate the shared efforts of European peoples to create a ‘great and wonderful spiritual edifice.’” Of course, these exalted aspirations remain almost as elusive today as they were then.

STILL, PROCHNIK’S supple defense of Zweig may not even be entirely necessary. For one thing, Arendt’s critique assumes that Nazism was inevitable. It’s easy enough to say in hindsight that Jews in Austria or Germany were blind to the looming peril, but they weren’t endowed with political clairvoyance. There was no guarantee that Hitler would come to power and, indeed, had the German elite resisted him in January 1933, he most likely would have become a spent force. The criticism also makes the assumption that a writer has a moral obligation to take a political stand, to act as a kind of Praeceptor Germaniae. It envisions Germany as the land of Dichter und Denker, the poets and thinkers.

This romantic belief—the fusion of spirit and power—lingers on in Germany today, where authors on the right (Martin Walser) or left (Günter Grass) periodically issue their addresses to the German nation. But it’s not clear that these interventions have ever been all that instructive or profitable. In fact, the record of German intellectuals, at least when it comes to political pronouncements, is pretty dismal. Stefan George started his own authoritarian cult. Bertolt Brecht, cynical and opportunistic, embraced, or pretended to embrace, Communism, setting up shop in East Germany. Martin Heidegger supported the Nazi movement during its early days. And Thomas Mann espoused anti-Western sentiments during World War I in his murky Reflections of an Unpolitical Man, which appeared to posit a German spirit superior to that of the decadent and corrupt West—though Mann, of course, became a foe of the Nazis and effectively repudiated his earlier work.

In moving to Brazil, Zweig appears to have tried to say goodbye to all that, to recuse himself from a world seemingly intent on self-destruction. Like Austria, it was a polyglot country, but here, so Zweig thought, everyone seemed to mingle peacefully, in contrast to the bloody ethnic quarrels of Central Europe. He even wrote one last book, a tribute to his hosts, called Country of the Future. But Zweig clearly didn’t believe that he had a future, here or anywhere else. Soon he divested himself of his remaining belongings. In February 1942, he created a bonfire in his garden and consigned his papers to the flames. Then came the doses of Veronal and a farewell letter: “I think it better to conclude in good time and in erect bearing a life in which intellectual labor meant the purest joy and personal freedom the highest good on earth.” Flower-bedecked coffins were carried through town. Petropolis shut down for the day. Zweig could only ask, like the disconsolate Franz Ferdinand Trotta in Roth’s final novel The Emperor’s Tomb, “Where can I go now, I, a Trotta?” It was a question that the possessor of Goethe’s pen was unable to answer.

Jacob Heilbrunn is editor of The National Interest.

Image: Wikimedia Commons/aconcagua. CC BY-SA 3.0.