The Myth That Empowers Islamic Terrorism

Radicals are exploiting a common misunderstanding of sharia.

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi is a man of mystery. Fascinating as he is dangerous, I contend that the only thing you need to know about him is that he is a religious scholar.

This is because Baghdadi is not alone as a terror leader; the founding or operational leaders of other major terrorist groups in the news—the Taliban, Boko Haram and Al Qaeda—are also religious figures such as clerics or Islamic scholars: namely, Mohammed Omar, Mohammed Yusuf and Abdullah Azzam, respectively.

Why have religious leaders come to play such an important role in violent radicalism, how did this all start, and what is the basis of their support?

For starters, the defining trend of recent centuries is the worldwide embrace of modernity and the socioeconomic advances brought about by science. As science began to replace religion as a source for understanding the world, secularists began growing in influence at the expense of religious leaders.

A manifestation of this trend in the Muslim world is rule by secular regimes and the domination of the public space by moderate elements. Unfathomable as this may seem now, even up until the 1970s, it was common for Kabul women to wear Western clothing and mix freely with men. A characteristic of this era was the absence of Islamist militant groups. Evidently, along with other religions, the forces of modernity were pushing Islam into a reformation.

Now, in Kabul, regressive religious forces have advanced at the expense of modernity. If we can understand why and how this transformation came about, perhaps, the genie may be put back in the bottle.

This is where Saudi Arabia’s decades-long propagation of Wahhabi version of Islam comes into the picture.

A standout feature of Wahhabism is its emphasis of the simple theme of sharia as all-encompassing divine law. While sharia in this context is regarded as an essential guide to life, it is a particular religious leader’s interpretation of Islam. As has long been familiar to the Muslim masses, interpretations of sharia vary widely and, in general, reflect the cultural norms of the Arab tribes of a bygone era.

Unlike most Muslim-majority nations, sharia interpretations provided by religious leaders form the source of the law in Saudi Arabia. This has put religious leaders—who are well-established in the society and have the wherewithal and self-interest to push a regressive agenda—at the center of its power structure. Indeed, they advance such an agenda, for example, in the form of a controlling religious police that is responsible for enforcing sharia compliance.

Another prominent feature of Wahhabism is its emphasis of armed jihad, or religious war, whose interpretations range from defensive to offensive ones. Saudi Arabia has a proven track record of sponsoring armed jihad (directed at the former Soviet Union’s occupation of Afghanistan). Saudi Arabia’s religious bona fides also stem from its status as the birthplace of Islam and home to its two holiest mosques.

The discovery of oil wealth not only helped Saudi Arabia forsake instituting political, economic and religious reforms, but also allowed it to export Wahhabism worldwide, by providing funds for constructing and operating mosques and religious schools, scholarships, education materials, religious leaders’ salaries and the employment of millions of guest workers from Muslim-majority nations.

Indeed, a leading Saudi government-funded charity involved in spreading Wahhabism worldwide, The Muslim World League, calls on “individuals, communities, and state entities to abide by the rules of the sharia.”

The Saudi effort has been consequential.

My new analysis of a 2013 START (Study of Terrorism And Responses to Terrorism) report reveals that in terms of the number of fatalities, the top eight terrorist groups are of the Islamist variety, and altogether constitute over 95 percent of the fatalities induced by the top ten terror groups.

The top three—together inducing 65% of the fatalities—are the Taliban, Islamic State and Boko Haram, which are either founded or led by the aforementioned religious leaders.

This is no coincidence. The militant groups that wage armed jihad for the purported cause of making sharia as the law of the land must rely on religious leaders for their exegetical expertise and as a conduit to the public. Religious leaders, especially radical ones, have every interest in enabling sharia as the law of the land.

There exists significant support among religious leaders for armed jihad in some nations. For example, even in countries such as Egypt and Saudi Arabia, where the governments have long coopted religious institutions, a significant subset of the religious leaders have espoused armed jihad. I used the results of a public poll in Pakistan to suggest that over 25 percent of all religious leaders there view jihad exclusively in an armed context.

In Saudi Arabia and Pakistan, where support for sharia and religious leaders are high, religious education is being emphasized at the expense of modern subjects. This has undoubtedly caused socioeconomic stagnation, and has made armed jihad a vocation for many unemployed and underemployed youths.

What is the basis of religious leaders’ influence, and how is it connected to violent radicalism?

My published analysis of a 2013 Pew Research Center report reveals that a public’s support for religious leaders’ role in politics rises and falls with its support for sharia as the law of the land. This correlation suggests that the extent of religious leaders’ influence in a community stems from their role as the primary interpreters of sharia and is dependent on sharia’s popularity. Thus, it is in the leaders’ interest to promote sharia.

In those nations with entrenched violent radicalism, sharia and religious leaders tend to be highly influential. This observation is supported by an analysis of a 2002 poll conducted in fourteen Muslim nations, which concluded that those who support a larger role for religious leaders in politics are more likely to support terrorism.

Notably, if support for sharia law is less in the community, so is the influence of religious leaders, and in general, so is the extent of violent radicalism there. This suggests that any scriptural content deemed offensive does not necessarily become material for incitement in such communities, because those who can credibly invoke them—religious leaders—have low levels of support.

Any significant local support for sharia can have far-reaching consequences. ISIS has even managed to successfully recruit youths from European Muslim communities who are neither religious nor well-informed on sharia, but are attracted by the popular and esteemed local cause of advancing a sharia-governed caliphate and the thrill of waging armed jihad.

A measure of the current state of knowledge and policies it entails is elucidated in President Obama’s speech at the 2015 “Summit on Countering Violent Extremism.” The speech steered clear of the aforementioned dynamic of religious leaders and sharia, but instead chose to single out “ideology/ideologies” as the cause, without elaborating or identifying their basis.

Is there more to sharia’s influence than what meets the eye? Perhaps—if the extent of radicalism and socioeconomic stagnation in sharia-governed, but oil-rich Saudi Arabia is any indication.

Central to religious leaders’ influence, it now appears, is the popularity of the narrative that sharia is an all-encompassing “divine law.” But sharia is merely religious leaders’ interpretation of Islam. This is a little secret that Baghdadi may not want you to know.

Moorthy S. Muthuswamy is a Fellow at the American Center for Democracy. He is author of Defeating Political Islam: The New Cold War (Prometheus Books, 2009).

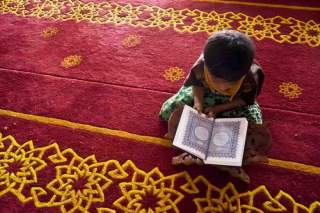

Image: Flickr/Tanti Ruwani