U.S. Nuclear Strategy and the Future of Arms Control

Pessimism about Chinese or Russian intentions is certainly warranted, but their future capabilities for carrying out a disarming first strike are uncertain.

According to recent press reports, the Biden administration has approved a secret nuclear strategy designed to adapt U.S. defense planning to the anticipated rise of China as a third nuclear superpower, continuing competition from Russia, and possible challenges from North Korea. The highly classified document approved in March 2024 seeks to adjust what is called “Nuclear Employment Guidance” to a new international environment of competing and colluding, hostile nuclear powers.

In June 2024, Pranay Vaddi, the senior director for arms control and nonproliferation at the National Security Council, noted that the new strategy emphasized “the need to deter Russia, the PRC, and North Korea simultaneously.” The Biden strategy reflects the Pentagon’s projections that China will expand its long-range nuclear weapons to 1,000 by 2030 and 1,500 by 2035, approximately the same numbers as those currently deployed by the United States and by Russia.

On the other hand, noted scholar and national security analyst Theodore Postol contends that the Biden strategy is no more than a tacit acknowledgment of a decade-long U.S. technical program to improve U.S. capabilities “to fight and win nuclear wars with both China and Russia.” According to Postol, a relatively new “super-fuse,” already being fitted onto all U.S. strategic ballistic missiles, more than doubles the ability of the Trident II D-5 Submarine Launched Ballistic Missiles (SLBMs) to destroy Russian and Chinese nuclear-armed intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) in hardened silos.

As he explains, the current U.S. nuclear ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) force has “about 890 W-76 100 kt and 400 W-88 475 kt warheads.” The 400 W-88 warheads equipped with the super-fuse have the combined accuracy and yield to destroy Russian silo-based ICBMs before they can be launched. However, these numbers of W-88s are insufficient to destroy both Russian and (expected numbers of) Chinese ICBMs before launch. Therefore, arming the W-76 warheads with super fuses means that:

“It is now possible, at least according to nuclear-war-fighting strategies, for the United States to attack the more than 300 ICBM silo-based ICBMs that China has been building since about 2020 with the copious numbers of available 100kt W-76 Trident II warheads. The rapid expansion in “hard-target kill capability” of the 100kt W-76 warhead also makes it simultaneously possible for the United States to attack the roughly 300 silo-based Russian ICBMs.”

Postol contends that the improved hard target kill capabilities will enable a preemptive U.S. strategy, at least as perceived in Moscow and Beijing, and lead both Russia and China to take reactive countermeasures that increase the degree of nuclear deterrence instability.

The Biden strategy calls for further discussion with respect to the assumptions about China’s nuclear rise and the most appropriate response to that eventuality, should it occur. The Postol account of U.S. nuclear warhead modernization warns against the effects of undisciplined technicism without inspection of the larger contexts of policy and strategy surrounding technology innovation. Further discussion will contextualize both China’s growing nuclear capabilities and concerns about the deployment of U.S. or other first-strike-enhancing technologies within the broader compass of nuclear deterrence stability and arms control.

Biden’s Nuclear Strategy and China’s Rise

Regarding the Biden nuclear strategy, the assumption that China will necessarily seek to maximize its numbers of strategic nuclear delivery systems between now and 2035 is not necessarily an incontestable proposition. China has several options for building its future military forces, including nuclear forces.

First, China might decide that a minimum deterrent is sufficient. A minimum deterrent would provide them with enough survivable long-range weapons to inflict unprecedented damage against an attacker’s economy and society, including its largest population centers, and against selected civil and military infrastructure.

Second, China might favor an assured retaliation plus a flexible response strategy. This definition of employment policy would include the ability to launch strikes against enemy nuclear retaliatory forces, political leadership, nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) systems, and selected conventional forces, in addition to those covered by minimum deterrence.

Third, a more ambitious strategy would include, in addition to minimum deterrence and assured retaliation requirements, capabilities for extended nuclear warfighting and enduring NC3 systems, post-attack survivability for political and military leadership, and options for neutralizing enemy space control and cyber defenses.

Thus far, it appears that China’s aspirations with regard to nuclear modernization and employment policy have moved away from the first option and toward the second. Pacing or outdoing the United States and Russia in the more ambitious third strategy by the mid-2030s would require financial and military commitments that divert resources from other purposes and, in the event, would stimulate countermeasures from Washington and Moscow. Regardless of the current “bromance” between President Vladimir Putin and President Xi Jinping and joint military exercises conducted by the two sides, neither Russia nor China can rule out the possibility of future adjustments in policy leading to cooler or even conflictual objectives in Asia. Therefore, while China’s nuclear rise explicitly threatens the United States in the near term, it also implicitly threatens Russia in an uncertain future of global geopolitics and enhances China’s strategic ambitions to become the world’s leading great power.

The preceding analysis does not necessarily mean that China intends to be the leading global military power per se. China’s military, including its nuclear forces, is only one component of a holistic strategy that seeks to maximize its global political, economic, technological, and other instruments of influence. China’s nuclear forces are intended as instruments of deterrence and armed persuasion that forestall any efforts by other powers to use their nuclear weapons for coercive diplomacy, including threats to conduct large-scale conventional war against China in the Indo-Pacific theater of operations. From this perspective, China seeks regional conventional military superiority supported by its nuclear forces as instruments of an anti-access/area denial (A2AD) strategy in the South China Sea and the first and second island chains.

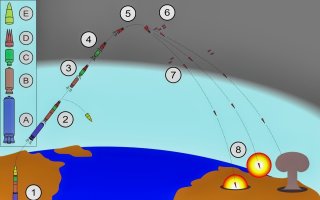

Finally, concerning the specifics of China’s strategic nuclear force modernization, the PRC is a long way from fielding a triad of delivery systems comparable to the diversity of U.S. land-based ballistic missiles (ICBMs), submarine-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs) and long-range bombers. The diversity of delivery systems in the U.S. strategic nuclear arsenal ensures against any successful preemptive first strike by either Russia or China, or both. This last observation is contestable with respect to future deployments by the powers compared to its currently available forces. Some imagine a future in which China and Russia might gang up on the United States with combined strategic nuclear forces capable of executing a disarming nuclear first strike.

Pessimism about Chinese or Russian intentions is certainly warranted, but their future capabilities for carrying out a disarming first strike are uncertain. Experts estimate that China has already produced and deployed a stockpile of about 440 nuclear weapons for delivery by land-based ballistic missiles, sea-based ballistic missiles, and bombers. Approximately sixty additional warheads may also have been produced, with more in production, eventually enabling the PRC to arm additional road-mobile and silo-based missiles and bombers. This is consistent with the U.S. Department of Defense estimates that the PRC possessed over 500 operational nuclear warheads in May 2023 and will probably have more than 1,000 by 2030.

Each arm of the currently deployed U.S. strategic nuclear triad is scheduled for qualitative upgrades into a new generation: Sentinel ICBMs; Columbia-class ballistic missile submarines (SSBNs); and B-21 Raider long-range bombers. U.S. nuclear C3 systems are also being upgraded, including their space-based components. Assuming the fulfillment of the Biden administration’s nuclear modernization plans into the 2030s by his successors, a robust strategic nuclear force posture will confront potential aggressors. In addition, the United States may be able to deploy next-generation anti-missile and air defenses in another decade, which will further complicate enemy nuclear first-strike planning and, in particular, address concerns about hypersonic weapons in that regard.

U.S. Warhead Modernization

In contrast to concerns about nuclear modernization plans by U.S. adversaries, Theodore Postol warns that the United States may be placing itself into a race that will lead Russia and China to improve first-strike capabilities. Faced with an American warhead modernization program that will place at risk increased numbers of Russian and Chinese ICBMs, they will have little choice but to respond, and perhaps asymmetrically. Dr. Postol notes the example of Russia’s Poseidon autonomous nuclear-powered and nuclear-armed unpiloted underwater vehicle (UUV) as one example of an asymmetrical response to improving U.S. first-strike capabilities.

On the other hand, U.S. military planners recognize the need to preserve a certain proportion of the sea-based strategic deterrent for later stages of employment instead of first strike forces. Assuming a future U.S. sea-based deterrent of twelve Columbia-class SSBNs, with ten operational at any given time, planners would want to preserve at least six boats for retaliation missions instead of preemption.

Moreover, of ten available boats, not all are at their assigned patrol destinations at the same time: some are returning from patrol locations, and others may be heading for patrol destinations. The first-strike vulnerability of U.S. ICBM and bomber forces is much higher than the vulnerability of ballistic missile submarines and their SLBMs. Using SSBNs as first-strike weapons can also give away their locations. Surviving U.S. sea-based nuclear forces is essential for posing a continuing threat to Russian or Chinese high-value targets, including their remaining nuclear forces, command-control systems, conventional forces, and economic infrastructure, following an enemy first strike. Thus, U.S. nuclear war plans will almost certainly assign some prompt counterforce missions to ICBMs instead of SLBMs.

In addition, not all Russian and Chinese ICBMs are deployed in silos. Russia has significant numbers of ICBMs in mobile basing, and China is thought to have significant numbers of long-range missiles that are mobile and based in underground tunnels. In Russia’s case, its survivable ICBMs are supplemented by its Borei-class ballistic missile submarine force with Bulava missiles, providing an additional survivable component to its deterrent and carrying a nontrivial number of warheads.

China’s SSBN/SLBM force is inchoate and small compared to Russia’s or the United States’, but China is intent on improving its sea-based deterrent to upgrade that portion of its strategic nuclear triad. Neither China nor Russia has a strategic bomber force that matches America’s current and future forces, but bombers are not competitive with missiles as first-strike weapons. If it can survive enemy first strikes, however, the U.S. strategic bomber force can contribute significantly to post-attack strikes and deterrent missions.

Nuclear policy expert Henry Sokolski has noted that growing numbers of Chinese and Russian nuclear weapons may pose insuperable challenges to U.S. force modernization, especially with regard to damage limitation objectives in U.S. nuclear employment policy. He proposes that, instead of expanding the U.S. nuclear arsenal to maintain a high level of damage limitation, policymakers should consider another approach to making an enemy first strike implausible or impossible. The alternative is an exponential growth in the number of possible aim points that China and Russia would have to target to neutralize America’s deterrent. For example, silo-based ICBMs could be transitioned to mobile basing, and alternative basing on commercial aircraft, trains, and ships should also be explored. Ultimately:

“Instead of Russia and China needing hundreds of nuclear-armed missiles and thousands of nuclear warheads to accomplish [a successful first strike], you would want to force them to require tens of thousands of warheads—and still not be confident of knocking out all of America’s nuclear force.”

From a scientific perspective, Dr. Sokolski’s proposal has appeal, but as a political proposition, it is likely to meet with strenuous objections from the U.S. strategic planning and policy communities. Intelligence estimation dealing with tens of thousands of warheads on each side would be challenging to existing capabilities for monitoring and verification of weapons deployments. Arms control would, therefore, become more complicated and possibly unmanageable in practice. Reciprocal competition in creating additional aim points for strategic weapons could expand the list of weapons and launchers demanded by Chinese, Russian, and American militaries in order to restabilize deterrence. In addition, a “successful” standoff in nullification of a comprehensive first strike could drive competition into more limited first strike opportunities against selected targets among U.S. allies in Europe and Asia. Another likely outcome, if comprehensive attacks via heavy metal are precluded, is that states will look in other directions for strategic surprise: strikes against space-based assets for warning, attack assessment, reconnaissance, communications, and geolocation, as well as attacks on cyber defenses.

As opposed to simply upgrading warheads or deploying newer generations of launchers, the major nuclear powers might seek tacit or explicit arrangements to limit the “bonus” from nuclear first strike as a last resort, i.e., preemption, relative to riding out the attack and retaliating. Hypersonic weapons pose a particular problem in this regard. Hypersonics threaten to reduce the amount of time available for warning, attack characterization, and response to any nuclear first strike. In addition, some hypersonics can be equipped with evasive countermeasures to ballistic missile and air defenses. The proliferation of nuclear-armed hypersonic glide weapons or hypersonic cruise missiles would create additional pressures for automation of the nuclear response process by artificial intelligence or other digital decision aids. Faced with the possibility of imminent threats involving little or no warning time, decision-makers could be tempted to prioritize preventive instead of preemptive first strikes under crisis conditions.

Planning for the Future(s)

China’s nuclear rise is a matter of imminent concern to U.S. political leaders and their military advisors, and China’s ambitions to become a global nuclear superpower merit close attention. On the other hand, China’s nuclear modernization ambitions are not necessarily inconsistent with nuclear strategic stability and the control of future arms races. China has options among alternative nuclear futures, and even under its currently projected levels of deployment (1,000 weapons on international launchers by 2030 and 1,500 weapons by 2035), China would remain within the envelope of strategic nuclear weapons deployed by the U.S. and Russia under existing New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) protocols. U.S. planners are understandably concerned about the possibility of combined Sino-Russian nuclear attacks or coercive diplomacy. Still, Chinese and Russian interests do not always line up on the use or threat of nuclear weapons. Moreover, neither U.S. nuclear warhead modernization nor Chinese nuclear expansion can create a first-strike capability that can prevent unacceptable and historically unprecedented retaliation against the attacker or attackers. Nuclear employment policy matters insofar as it reinforces deterrence; otherwise, it is the pursuit of dead ends.

Stephen Cimbala is a Distinguished Professor of Political Science at Penn State Brandywine and the author of numerous books and articles on international security issues.

Lawrence Korb, a retired Navy Captain, has held national security positions at several think tanks and served in the Pentagon in the Reagan administration.

Image Credit: Creative Commons/Wikipedia.