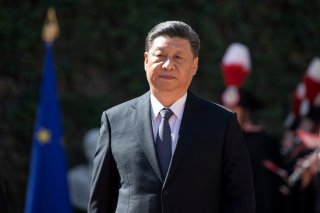

What If Xi Jinping Was Framed for the Chinese Balloon?

Xi had no reason to send an obvious and provocative espionage balloon into American airspace. Other factions within the CCP, however, did.

As the Chinese spy balloon hovered over Montana, Secretary of State Anthony Blinken made the decision to postpone his scheduled visit to China. The stakes of that visit were already high, with the two sides expected to discuss the ongoing semiconductor chip embargo, Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy’s visit to Taiwan, the war in Ukraine, and more. Now, neither side will have that opportunity. President Joe Biden promises that the balloon incident will not ultimately weaken U.S.-China relations, but there is little doubt that domestic pressure to get tougher on the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has intensified.

By no stretch of the imagination does this look like what Xi Jinping would have wanted, especially at this juncture. Not long ago, the CCP had extended an olive branch to the United States and the West, hoping to improve relations in ways that would benefit Chinese trade with Europe and America and allow greater proximity to its greatest political rival. China’s ambassador to the United States, Qin Gang, had taken advantage of that emerging proximity, personally attending a Washington Wizards game and sending Chinese New Year greetings to the American audience before the game. Such efforts will now be put on hold following the balloon incident.

Given the negative fallout that was sure to come in the wake of flying a massive spy balloon in Western skies, why would the CCP have made such a move? One possible explanation is that this was part of China’s espionage routine, and that the CCP wanted to project a strong image ahead of Blinken’s visit. That explanation assumes, however, that China was unprepared for the strength of the American diplomatic response—something that seems unlikely from a country as sophisticated as China. What Xi Jinping needs right now is to de-escalate tensions with the United States, and serious provocations flown in American skies run counter to that goal. And if Xi truly wants to show his military might to Washington, a balloon is too light a weight.

According to the Wall Street Journal, the top Chinese leadership might not have even been aware of the balloon before it was informed by the U.S. State Department. How can it be that “U.S. officials are confident, however, that China directed the balloon” although “they don’t know if Beijing initially intended for the balloon to travel south over the U.S. heartland after it ventured over Alaska.”

If launching the balloon over the U.S. territory was not Xi Jinping’s idea, that leaves two distinct possibilities. One possibility is that certain Chinese bureaucrats were politically insensitive enough to release the balloon over the United States before Blinken’s visit without asking Beijing for permission. A second possibility is that this was done by internal opposition to Xi, with the intention of further straining U.S.-China relations and making an international mockery of Xi's leadership. The latter possibility is no less likely than the former.

In either case, who is the likeliest “candidate” that is out of step with Xi Jinping? Quite likely, it would be the Chinese military.

On February 4 the U.S. Department of Defense issued a statement refuting the Chinese claim that the balloon was a mere weather balloon. In the statement, a senior official stated that “This was a PRC surveillance balloon. This surveillance balloon purposefully traversed the United States and Canada. And we are confident it was seeking to monitor sensitive military sites. Its route over the United States, near many potential sensitive sites, contradicts the PRC government’s explanation that it was a weather balloon.”

This claim is bolstered by Chinese companies’ own claim that they produce such balloons for military use. For example, according to the website of China Zhuzhou Rubber Research & Design Institute Co Ltd., it is a government-owned military research institute with weapon production licenses. Its military supporting products were used in the “Shenzhou V” manned spacecraft, and have won the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) General Armament Department commendation. It is a designated research institution for the weather balloons of all military branches of the PLA.

Following the shooting down of the first balloon, the United States swiftly sanctioned six Chinese companies involved in the production of such balloons.

Chinese law also provides circumstantial evidence that this is a military balloon. According to Article 70 of the Civil Aviation Law of the People’s Republic of China, the state shall exercise unified management of the airspace. This means that private individuals are prohibited from launching any flying objects without government permission. Thus, a massive surveillance balloon sent into the stratosphere and left hovering over the United States for multiple days could not be the act of a civilian company—this act must have been sanctioned by someone in the military or government, with the former being a likelier suspect given its direct responsibility over securing airspace.

It is possible the balloon could have been part of a military research project, and such projects are generally not reported to Xi Jinping. Approval from a military intelligence organization, such as the PLA’s Intelligence Bureau of the Joint Staff Department, would suffice. But the usage of this balloon was far from a routine experiment, given its sensitive timing and the balloon’s lengthy stay in the United States. This has given rise to speculation that it was meant primarily for Americans to see, causing a surge of negative opinions regarding the CCP.

This is not the first time a blunder by the Chinese military, at a critical moment and in direct opposition to Xi Jinping’s wishes, has left him in an embarrassing diplomatic position. In September 2014, Xi Jinping visited India for the first time as general secretary of the CCP. This was a critical visit, involving twelve key agreements between the countries—including China’s commitment to invest $20 billion in India’s infrastructure over the next five years. But during the visit, border guards from both countries clashed along the India-China border. Indian media reported that, in the week prior, Chinese troops built a temporary road across the Line of Actual Control in the disputed border area of Ladaka and into Indian territory. India mobilized thousands of troops to the area to confront a significant number of Chinese soldiers. In a joint press conference after the talks, Modi called for a “clarification” of the Line of Actual Control on the border, putting Xi Jinping in an awkward position.

Xi’s predecessor, Hu Jintao, faced a similar situation when he met U.S. Defense Secretary Robert Gates on January 11, 2011. On the day of the meeting, China conducted a test flight of its newly developed J-20 fighter jet. Gates confronted Hu about the flight, asking if the move was directly related to his visit. Hu made clear that he had no prior awareness of the military maneuver, discovering the details only after he asked Chinese military personnel about it following his discussion with Gates.

Hu Jintao did not take control of the military during his tenure—it was essentially under the control of his predecessor and political rival, Jiang Zemin. This situation has continued into the Xi Jinping era: although Xi has made sweeping reforms to the military, promoting a large number of people he trusts to be senior generals (such as war zone commanders), the military is still not fully under his control. Chinese military sources have told me that many senior generals are estranged from the troops under their command.

By the time of the 20th National Congress, Xi Jinping had essentially crushed any opposition to him. At least on the surface, no one dares to oppose him. However, his tendency to place his own political allies in key positions has alienated large numbers of CCP cadres. But with his stronghold on control of the country, there is little they can do internally. In the minds of Xi’s opponents, the only one who can truly deal a heavy blow to Xi now is the United States.

Yet Xi and the CCP are now inextricably linked. Xi has tied the fate of the Communist Party to his own. And Xi’s—and thus, the CCP’s—fundamental view of the United States will not change. In light of this, the United States needs to remain acutely aware of a few things.

One is that the balloon incident, which has increased public pressure to get tougher on the CCP, has the potential to tighten the alliance between the Chinese Communist Party and Russia. Since the incident reinforces Xi’s understanding that the overall trend in U.S.-China relations is towards rivalry and confrontation, he may cling ever more tightly to his relationship with Russia, currently China’s only ally with international military and political strength.Without Russia, China would stand alone in its confrontation with the West. And, if China were to attack Taiwan by force in the future, it would need a steady rearguard. Whether they have a friend or a foe on the other side of the 1,000-kilometer Russian-Chinese border will determine whether China dares to fight with confidence in the front.

To maintain the surety of that rearguard, China has continued to support Russia in its aggression against Ukraine. The Wall Street Journal recently revealed that import and export data from Russian customs obtained by C4ADS, a nonprofit organization, demonstrate that Chinese state-owned defense companies have been shipping navigation equipment, jamming technology, and jet fighter parts to sanctioned Russian state-owned defense companies since the start of the Russo-Ukrainian War. In addition, Russian imports of computer chips and chip components have now largely reached pre-war averages. Most of these shipments come from China.

The promise made to Vladimir Putin last year by Li Zhanshu, chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People’s Congress, that China would support Russia, was not false—and the overall pattern of the CCP’s confrontation with the West, with Russia as an ally, will not change. The Russo-Ukrainian War, if ending in a Ukrainian victory and Putin’s ouster or Russia’s fall to the West, would be a heavy blow to Xi and the CCP. In that case, Europe and the United States would no longer face a security threat from Russia, leaving them free to focus their collective energies on dealing with the CCP. That situation is unwelcome enough in the eyes of Xi, incentivizing him to possibly offer his services as a mediator between the West and Russia in negotiations for an early end to the war while keeping Putin in power. This move though should not be seen as evidence of solidarity with Western values and intentions—rather, it is a self-serving means to preserve their military and economic strength to battle the West, including preparing for a larger war in the Taiwan Strait.

Simone Gao is a journalist and host of Zooming In With Simone Gao, an online current-affairs program.

Image: Shutterstock.