What the World Can Learn from Taiwan's China Experience

Nations large and small are trying to benefit from the upside of China’s ascent while managing the attendant geopolitical risks.

As China’s economic gravity becomes inescapable and its military reach extends into the Western Pacific and the Indian Ocean, nations large and small are trying to benefit from the upside of China’s ascent while managing the attendant geopolitical risks.

China’s continued rise presents a series of balancing acts. How to engage China economically while limiting vulnerability to coercion. How to welcome Chinese foreign-direct investment (FDI) while protecting critical sectors of the economy. And, how to maintain a credible military deterrent with limited defense resources.

Due to its unique position as an island democracy that China regards as a breakaway province, Taiwan has struggled with these balancing acts for years. Its successes and failures are instructive, pointing the way for countries only now coming to grips with the reality of Chinese power and influence.

Economic Engagement Versus the Danger of Coercion

Economic engagement with China—ranging from trade to investment to tourism—has become an imperative for every nation in search of opportunities to boost domestic growth. Globally, more than 120 countries now count China as their largest trading partner. China has rapidly become a leading source of outbound FDI flows. From Japan to Southeast Asia to Australia, Chinese visitors have become an important driver of the domestic tourism industry.

Although economic engagement with China can yield substantial benefits, the often-lopsided interdependency that results provides Beijing with a basis for exerting coercion. Taiwan’s experience offers nations both a cautionary tale and a potential way forward.

In the period following China’s economic opening under Deng Xiaoping, Taiwan led the way in economic engagement with China. Cross-Strait trade, investment and tourism linkages blossomed. Economic ties with China bolstered Taiwan’s economy, which benefited from moving factories across the Strait to take advantage of the mainland’s considerably cheaper labor costs, and also ramped up exports to meet the insatiable demand presented by China’s ballooning domestic market. Over time, Taiwan became profoundly entangled with China economically. As of 2015, roughly 40 percent of Taiwan’s exports went to China, the stock of Taiwanese investment in the mainland reached approximately 133 billion U.S. dollars, and visitors from China, while recently declining, still generate 3.5 million customers for Taiwan’s domestic businesses and tourism markets annually.

Yet this lopsided interdependence has translated into vulnerability to Chinese coercion. Reacting to the election of Taipei’s more China-skeptical president, Tsai Ing-wen, Beijing curtailed the number of Chinese tourists to Taiwan. China’s trade volume with Taiwan in 2016 also fell by 4.5 percent. This economic pressure had a clear intended outcome: to compel Tsai to affirm an oral statement in 1992 by the leaders of Taiwan and mainland China agreeing on the existence of an undefined “One China.”

To its credit, Taiwan has started to take steps to limit its vulnerability to economic coercion. In a bid to balance its dependence on China, Taipei has pursued closer ties with Southeast Asia, Australia, New Zealand and South Asia. Taiwanese investment to Southeast Asia has doubled, and as tourism from China declined, visitors from the rest of Asia have surged.

Even nations with seemingly cordial relations with Beijing can quickly become targets for economic coercion, as China’s economic punishment of South Korea following the deployment of a U.S. missile defense system there made eminently clear. Taiwan’s initial success in diversifying its economy away from China should serve as a guiding example for countries throughout Asia now dangerously over dependent on China for trade and investment.

Chinese FDI Versus Protecting Economic Crown Jewels

Long a major recipient of FDI, China has become a leading investor globally. While China’s outbound investment initially focused on extractive industries clustered for the most part in developing countries, more recently, its companies have piled into advanced economies. For example, in the United States, Chinese investment more than tripled in 2016 compared to the prior year.

Chinese investment in advanced economies promises to deliver significant welfare benefits in terms of short-term job creation. Yet it also presents a challenge to long-term economic competitiveness, with Chinese companies strategically investing in high-technology industries and startups in key fields, such as artificial intelligence and robotics. In recent months, American concerns about the implications of Chinese targeted investment have sharply risen, as exemplified by the U.S. president intervening to block a deal between a Chinese venture capital firm and a U.S. semiconductor company.

Taiwan has long navigated the delicate balance of how to benefit from an influx of Chinese money while protecting economic crown jewels. While China has invested in Taiwan’s high technology sector, which opened factories and research facilities across the strait, Taiwan has still managed to protect a key economic crown jewel—its world class semiconductor industry. These chip makers were excluded from the first wave of Chinese investment allowed into Taiwan, a policy that, while controversial, persisted through an era of economic rapprochement.

Now, despite growing pressure from domestic business, Taiwanese president Tsai Ing-wen has given even further scrutiny to Chinese investments in advanced technologies. Owing to concerns over China’s access to national-security critical and commercially-vital intellectual property, several high-profile microchip investment deals have fallen through in 2017 alone.

For advanced economies attempting to benefit from Chinese investment while still retaining key technologies that will drive long-term growth, the lesson from Taiwan is clear: take a targeted approach that focuses on a small set of genuine economic crown jewels.

Maintaining Deterrence Versus Limited Defense Resources

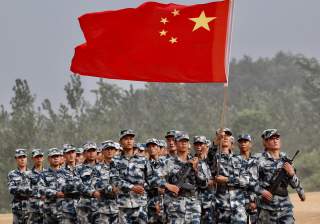

The Asia-Pacific security landscape increasingly features an imbalance of military power between China and its neighbors. Beijing’s long-term effort to modernize the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has paid off. With a blue-water navy, an increasingly cutting-edge air force, and a streamlined and more lethal army, China’s military has become a “high-tech force capable of regional dominance.” This transformation has erased longstanding sources of deterrence in the Asia-Pacific: the qualitative military edge that some U.S. allies and partners once enjoyed over China and the insurmountable power-projection challenge created by the region’s maritime geography.

For nations in China’s periphery, maintaining a conventional deterrent simply by spending more on national defense is infeasible. Democratic and not-so-democratic governments across the region must navigate the guns versus butter tradeoff. Even if they could ratchet up military expenditures, matching China would prove impossible: China’s military outlays in 2016 surpassed that of Japan, South Korea, Southeast Asia, Australia and India combined.

The deterrence predicament that many countries in the Asia-Pacific now confront emerged first for Taiwan. Leaving aside the potential for U.S. intervention, Taiwan’s qualitative military edge and the ninety miles of water separating it from mainland China constituted a foundation for deterrence until the 2000s. However, this foundation has substantially eroded as China has systematically invested in military capabilities needed to compel reunification.

Taiwan’s response illuminates the challenge of maintaining conventional deterrence amidst limited defense resources—a challenge that governments in China’s periphery increasingly face. Since the 2000s, Taiwan has grappled with how to strike the right balance between upgrading traditional military platforms, purchasing new weapons systems, and investing in asymmetric capabilities that could, at a relatively low cost, complicate China’s use of force. Within Taiwan, debates over the right balance remain ongoing. In practice, Taiwan’s government has gradually moved toward a hybrid approach that pairs selective investments in large-scale platforms, like submarines with asymmetric capabilities or like a highly mobile multiple-launch rocket system and upgrades to its supersonic anti-ship cruise missile.

If Taiwan can successfully execute this hybrid approach, it could serve as an example to other Asian militaries that seek to deter China’s use of force in a resource-constrained budgetary environment. If Taiwan fails, regional militaries, especially those with modest budgets, should learn a different lesson: avoid a hybrid approach and focus on low-cost, asymmetric capabilities as the best deterrent.

As China’s economic influence and military reach continues to expand, the balancing acts Taiwan has managed will become increasingly familiar to nations across the Asia-Pacific region and beyond. Unlike Taiwan, many will not have the advantage of vibrant democratic institutions, an advanced economy and a close security partnership with the United States. For these countries, learning from Taiwan’s successes and its mistakes is imperative; failure to do so could result in the erosion of sovereignty as economic and military vulnerability to China precludes any choice that contradicts Beijing’s will.

Daniel Kliman is a senior fellow for Asia-Pacific Security at the Center for a New American Security (CNAS) in Washington DC, and until July 2017, served in the Department of Defense. Harry Krejsa is the Bacevich Fellow at CNAS.

Recommended:

Why North Korea's Air Force is Total Junk