America, Not Duterte, Failed the Philippines

Washington pushed the Philippines away by failing to honor moral, if not legal, obligations to its long-standing ally.

“This is very alarming,” Bito-onon told Reuters. To inhabitants of the surrounding area, Beijing’s actions were a threat. “The Chinese are trying to choke us by putting an imaginary checkpoint there,” the mayor said. “It is a clear violation of our right to travel, impeding freedom of navigation.” Freedom of navigation has had no more staunch defender than the United States, but in recent years America has been reluctant to confront China as it attempted to restrict others in its peripheral waters. Washington’s abandonment of Manila was especially evident when an arbitral panel in The Hague handed down its landmark decision in Philippines v. China last July, invalidating the nine-dash line and ruling against China on almost all its positions.

The tribunal held that Mischief Reef and Second Thomas Shoal are within the Philippine exclusive economic zone and on the Philippine continental shelf, and that there was no basis for any claim by Beijing to these two features. With regard to Scarborough, it decided China had violated the traditional fishing rights of Filipino fishermen by exercising control of the shoal. Moreover, the panel ruled that Beijing had operated its vessels at Scarborough so as to create a “serious risk of collision and danger to Philippine ships and personnel,” breaching its international obligations. The Philippines, as a signatory to the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), brought the action in 2013, shortly after the Chinese had seized Scarborough. At first, Beijing did not realize the significance of the case filed by Benigno Aquino, Duterte’s immediate predecessor, but China eventually grasped its importance and contested the jurisdiction of the arbitral panel in December of the following year.

Beijing did not accept arbitration delimiting sea boundaries when in 1996 it ratified UNCLOS. Yet its ratification implicitly accepted arbitration of other matters. In October 2015, the arbitration panel asserted jurisdiction over seven of the fifteen claims raised by Manila. In response, China withdrew and did not participate in the substantive phase of the case.

Beijing denounced the 479-page award issued last July. It called the panel a “law-abusing tribunal,” the case a “farce.” The decision “amounts to nothing more than a piece of paper.” “The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China solemnly declares that the award is null and void and has no binding force,” Beijing announced on the day it was issued. “China neither accepts nor recognizes it.” Chinese experts, apparently speaking at the behest of their government, threatened war.

And Duterte, who assumed the presidency two weeks before the decision was handed down, had grounds to be even more upset at America. Secretary of State John Kerry did say China should accept the award, but he spoke without seriousness. He did not pressure Beijing to honor its obligation to accept the ruling, but instead leaned on Manila to bargain with China, backing the Chinese position on starting talks. Kerry’s posture was indefensible. Chinese officials had publicly refused to accept the award as the basis for negotiations. The secretary of state, it was clear, was more intent on avoiding confrontation with a lawless Beijing than upholding centuries of U.S. commitment to defend the global commons.

Duterte, among others, has noticed Washington’s reluctance to protect his beleaguered country. “America did nothing,” he said in October 2015, referring to China’s reclamation activity. “And now that it is completed, they want to patrol the area. For what?” His views on the topic have been nothing if not consistent. America, he maintained at the end of December, should have stopped China “when the first spray of soil was tossed out to the area.” “He feels aligning with our allies against China is not going to benefit the country,” said Jesus Dureza, Duterte’s close friend and cabinet-level peace adviser, describing the president’s views. “The idea is that our allies are not going to go to war for us, so why should we align with them?”

Perfecto Yasay Jr., Duterte’s foreign minister until March, expanded on this theme of betrayal. He noted the “stark reality” that the Philippines cannot defend itself and, in a Facebook post aptly titled “America Has Failed Us,” wrote,

Worse is that our only ally could not give us the assurance that in taking a hard line towards the enforcement of our sovereignty rights under international law, it will promptly come to our defense under our existing military treaty and agreements.

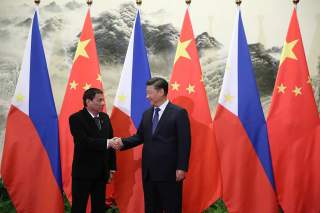

Moreover, Duterte has also made it clear he will not side with America because he believes that in East Asia it has already “lost,” something he made clear during his Beijing trip.

THE UNITED States has by no means lost in any sense of that term, but nuanced, hesitant-looking U.S. policies have created that impression. Washington, throughout the Bush and Obama administrations, inadvertently created the appearance of weakness, and the appearance of weakness is now costing Washington a crucial treaty ally. As Duterte, who obviously prides himself on his strength, makes clear, everyone wants to be on the winning side.

There are, however, several signs that the rift between Manila and Washington can narrow in coming months. First, American policies are moving in a direction more to the liking of the Philippines. The trend began sometime around the beginning of last year. “Early 2016 saw a perceptible uptick in American naval patrols and surveillance activities close to the Scarborough Shoal, which may have contributed to China’s decision to postpone any construction activity on the disputed feature,” Richard Heydarian, a foreign-affairs expert in Manila, told me.

Moreover, the Financial Times reports that last March, President Obama privately warned Chinese ruler Xi Jinping that he would do all he could to prevent the reclamation of Scarborough—“a stark admonition,” as the paper put it—and there are indications Obama repeated the stern words during the G-20 meeting in September in the Chinese city of Hangzhou. American efforts, Manila believes, had some effect. This March, Defense Secretary Delfin Lorenzana publicly suggested that Washington stopped China at the last minute from cementing over Scarborough. President Trump looks like he will continue to move in his predecessor’s more resolute direction. During his January confirmation hearing, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson stated that China would not be allowed to occupy its reclaimed features in the South China Sea. Moreover, White House spokesman Sean Spicer reiterated Tillerson’s position when he said that the administration would not permit China to grab disputed features. “Under Trump, there is growing confidence that the U.S. will adopt a more robust stance against China,” Heydarian notes about attitudes in the Philippine capital.

The new direction is the product of a realization that, for its own reasons, Washington must stop China from reclaiming and militarizing Scarborough. Militarization would allow the People’s Liberation Army to complete a triangle formed by the airstrip on Woody Island in the Paracels and the three runways on the seven reclaimed islands in the Spratly chain. The interlocking facilities would give Beijing the ability to enforce an air-defense identification zone over the South China Sea, much like the one it declared over the East China Sea in November 2013. Each year, some $5.3 trillion of goods passes on and over the South China Sea—much of it moving to or from the United States—so Washington does not want any other country, especially China, to control the skies over that crucial body of water.

Moreover, there is a sense in Washington that, as Beijing adopts progressively more hostile policies, it must keep China’s navy and air force penned inside what Chinese strategists call the “first island chain.” The Philippine president, who governs a sprawling archipelago in the center of that chain, could give China’s forces easy access out of the South China Sea to the Western Pacific, thereby exposing, among other things, Taiwan and the southern portion of Japan.

Second, nations other than the United States also have an interest in preventing the Philippines from becoming a Chinese dependency. Both South Korea and Japan are critically reliant on tanker shipments from the Middle East crossing the South China Sea. Seoul, now embroiled in a deepening political crisis, has no time for outreach to the Philippines. Tokyo, on the other hand, is working the problem hard. Its prime minister, Shinzo Abe, was the first head of government to pay a call to the country since Duterte took office, traveling to see the Philippine leader at his home in Davao City in January. Abe’s trip followed that of his foreign minister, Fumio Kishida, who was the first foreign minister to go there during Duterte’s administration.

In Duterte’s home, Abe shared a simple breakfast in the kitchen, and the Japanese leader brought gifts. Not only is Tokyo funding a drug-rehabilitation center—thereby helping the Philippine leader with his most important domestic initiative—it is also pledging $8.7 billion in assistance. Money talks loudly in Manila and helps Japan, a staunch U.S. ally, maintain a vital link between Washington and its most troublesome treaty partner. Tokyo, in short, may be the factor keeping Duterte from a final defection to China.