America, Not Duterte, Failed the Philippines

Washington pushed the Philippines away by failing to honor moral, if not legal, obligations to its long-standing ally.

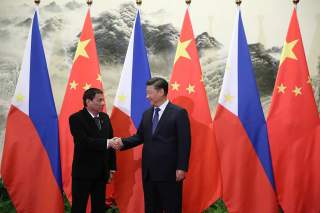

Third, Beijing will also impede Duterte from completing his pivot to China. After all, the Philippines, whether it publicly admits to it or not, is involved in a zero-sum contest with the Chinese state. Beijing now labels its South China Sea claims as “core” and “irrefutable,” and Duterte, although he can make temporary accommodations on issues like fishing rights, cannot compromise sovereignty. If he cedes territory as Beijing demands, he could lose his job. In October, on the eve of the president’s trip to Beijing, Supreme Court Senior Associate Justice Antonio Carpio remarked that Duterte can be impeached if he surrenders Scarborough Shoal. Duterte may say China “has never invaded a piece of my country all these generations”—what he told the Chinese during his October visit—but that is manifestly untrue. And Beijing is ramping up efforts to dominate specks that Filipinos believe are theirs.

Fourth, many in Manila are concerned about Duterte moving the Philippines into the Chinese sphere of influence. Among the pro-U.S. voices is the influential Fidel Ramos, a former president. Ramos, who has counseled Duterte, called his anti-U.S. statements “discombobulating,” and there is general concern in the Philippine capital about anti-Americanism getting out of control. The Philippine military, which has seen fit to change presidents from time to time, is almost uniformly pro-American.

These attitudes are in line with Philippine popular opinion. Poll after poll indicates general support for America, usually around 90 percent. No country, as the last Pew Research Center survey notes, has a more favorable view of the United States than the Philippines. And, predictably, poll after poll indicates that the Philippine public expects Duterte to defend the country’s sovereignty. A recent Pulse Asia survey showed that 84 percent of Filipinos want Duterte to assert rights over South China Sea features, in accordance with the July 12 Hague ruling. In a response to growing public concern, Foreign Minister Yasay revealed in January that he had filed formal protests with Beijing over its activities at Scarborough and in the Spratly chain.

FINALLY, DUTERTE’S ability to reorient Manila’s policy will eventually be undermined by an erosion in his popularity at home. So far, the president enjoys wide support, effectively giving him the latitude to do what he wants. Up to now, his war on drugs has been the centerpiece of his governance and, it appears, the main reason for his big following. The war, marked by extrajudicial executions and state-sponsored murders, has been bloody, claiming over seven thousand lives since his inauguration. During this period, police have been “pro-actively gunning down suspects,” the conclusion Reuters draws from a 97 percent kill rate in police raids.

“Duterte Harry’s” extraordinary campaign has encountered stiff opposition from the Catholic Church and human-rights activists, however, and the president has begun to feel the heat. One of the first signs of trouble for him appeared in late January when Malacanang Palace, the presidential office, had to ask the public to give the “Punisher,” another of Duterte’s nicknames, “an allowance for mistakes.”

Mistakes, like the October kidnapping and killing of a South Korean businessman by antinarcotics officers at the Philippine National Police headquarters, have already slowed his drug war, leading to the late January suspension of the effort. And as more horrible stories pile up, his brutal campaign will surely lose support as police excesses become too blatant—and as his attacks against the Church force the bishops to go on the offensive against him.

Furthermore, another bad sign for Duterte is the reports of growing corruption. The country fell on Transparency International’s Corruption Index last year, and the appearance of venality is something that will affect his legitimacy. Duterte should remember that another tough-guy president, Joseph Estrada, was ousted from power over the issue.

All these domestic trends are crucial because, as Duterte loses altitude, he will inevitably lose the clout to fundamentally change the balance of power in East Asia. Yet President Trump may only have a small window to reverse Manila’s course. In January, Duterte said he was going to Beijing in May to meet Xi Jinping again. That’s about the same time he is expected to travel to Russia.

Why is Duterte intent on traveling to Beijing and Moscow? In September, he said he might “cross the Rubicon” and end the mutual-assistance treaty with the United States in order to ink defense pacts with China and Russia.

Gordon G. Chang is the author of The Coming Collapse of China. Follow him @GordonGChang.

Image: President Rodrigo Duterte and President Xi Jinping shake hands prior to their bilateral meetings at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing on October 20, 2016. Wikimedia Commons.