China vs. Japan: Asia's Other Great Game

Beijing and Tokyo will undoubtedly compete long after U.S. foreign policy has evolved.

Asia’s Other Great Game

By Michael Auslin

*** “We confer upon you, therefore, the title ‘Queen of Wa Friendly to Wei’ . . . We expect you, O Queen, to rule your people in peace and to endeavor to be devoted and obedient.”—Letter of Emperor Cao Rui to Japanese empress Himiko in 238 CE, Wei Zhi (History of the Kingdom of Wei, ca. 297 CE) ***

*** “From the emperor of the country where the sun rises to the emperor of the country where the sun sets.”—Letter from Empress Suiko to Emperor Yang of the Sui Dynasty in 607 CE, Nihon Shoki (Chronicles of Japan, 720 CE) ***

THE SPECTER of the world’s two strongest nations competing for power and influence has created a convenient narrative for pundits and observers to claim that Asia’s future, perhaps even the world’s, will be shaped, in ways both large and small, by the United States and China. From economics to political influence and security issues, American and Chinese policies are seen as inherently conflictual, creating an uneasy relationship between Washington and Beijing that affects other nations inside Asia and out.

Yet this scenario often ignores another intra-Asian competition, one that perhaps may have as much influence as that between America and China. For millennia, China and Japan have been locked in a relationship even more mutually dependent, competitive and influential than the much more recent one between Washington and Beijing. Each has sought to dominate, or at least be the most influential in, Asia, and the relations of each with their neighbors has at various points been directly shaped by their rivalry.

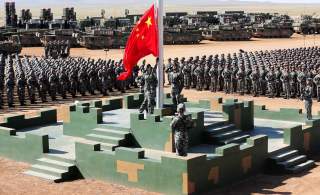

There is little question today that the Sino-American competition has the greatest direct impact on Asia, particularly in the security sphere. America’s long-standing alliances, including with Japan, and provision of public security goods, such as freedom of navigation, remain the primary alternative security strategies to Beijing’s policies. In any imagined major-power clash in Asia, the two antagonists are naturally assumed to be China and the United States. Yet it would be a mistake to dismiss the Sino-Japanese rivalry as a simple sideshow. The two Asian nations will undoubtedly compete long after U.S. foreign policy has evolved, and regardless of whether Washington withdraws from Asia, grudgingly accepts Chinese hegemony, or increases its security and political presence. Moreover, Asian nations themselves understand that the Sino-Japanese relationship is Asia’s other great game, and is in many ways, an eternal competition.

CENTURIES BEFORE the writing of Japan’s first historical records, let alone the formation of its first centralized state, envoys from its leading clan appeared at the court of the Han Dynasty and its successors. Representatives of the land of “Wa” were recorded as first arriving in Eastern Han in the year 57 CE, though some accounts place the first encounters between Chinese and Japanese communities as far back as the late second century BCE. Not surprisingly, these earliest references to Sino-Japanese relations are in the context of China’s intervention on the Korean Peninsula, with which ancient Japan had long-standing exchanges. Nor would an observer at the time be shocked by the Wei court’s expectation of deference to China. Perhaps slightly more surprising is the seventh-century attempt by an upstart island nation just beginning to unify to assert not merely equality but superiority over Asia’s most powerful country.

The broad contours of Sino-Japanese relations became clear early on: a competition for influence, an assertion by both of their respective superiority, and an entanglement with Asia’s geopolitical balance. Despite the passage of two millennia, the base of this relationship has changed little. Today, however, a new wrinkle has been added into the equation. Whereas throughout the previous centuries only one of the two nations was powerful, influential or internationally engaged in any given era, today both China and Japan are strong, united, global players, well aware of the other’s strengths and their own weaknesses.

Most American and even Asian observers presume that it is the Sino-American relationship that will determine Asia’s future, if not the globe’s, for the foreseeable future. Yet the competition between China and Japan has been of far longer duration and is of a significance that should not be underestimated. As the United States enters a period of introspection and readjustment in its foreign and security policies after Iraq and Afghanistan, as it continues to struggle to maintain its widespread global commitments and as the full scope of Donald Trump’s desired readjustment of U.S. foreign policy continues to take shape, the eternal competition between Tokyo and Beijing is poised to enter an even more intense period. It is this dynamic that is as likely in its own way to shape Asia in the coming decades as that between Washington and Beijing.

TO MAKE a claim that Asia’s future will be decided between China and Japan may sound fanciful, especially after two decades of extraordinary economic growth that has vaulted China into becoming the world’s largest economy (at least according to purchasing power parity calculations), and a concomitant quarter-century of apparent Japanese economic stagnation. Yet the same claim would have sounded just as unrealistic back in 1980, except in reverse, when Japan had racked up years of double- and high single-digit economic returns while China had barely emerged from the generational disaster of the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution. Just a few decades ago, it was Japan that was predicted to be the global financial power par excellence, countered only by the United States.

For most of history, however, it would have seemed delusional to compare Japan with China. Island powers rarely can compete with cohesive continental states. Once China’s unified empires emerged, starting with the Qin in 221 BCE, Japan was dwarfed by its continental neighbor. Even during its periods of disunity, many of China’s fragmented and competing states were nearly as large, or larger than, all of Japan. Thus, during the half-century of the Three Kingdoms, when Japan’s Queen of Wa paid tribute to Cao Wei, each of the three domains, Wei, Shu and Wu, controlled more territory than Japan’s nascent imperial house. China’s natural sense of superiority was reflected in the very word used for Japan, Wa (倭), which is usually accepted to mean “dwarf people” or possibly “submissive people,” thus fitting Chinese ideology regarding other ethnicities in ancient times. Similarly, Japan’s geographical isolation from the continent meant that the dangerous crossing over the Sea of Japan to Korea was attempted only rarely, and usually only by the most intrepid Buddhist monks and traders. The early Chinese chronicles repeatedly introduced Japan as being a land “in the middle of the ocean,” emphasizing its isolation and difference from the continent. Long periods of Japanese political isolation, such as during the Heian (794–1185) or Edo (1603–1868) periods also meant that Japan was largely outside the mainstream, such as it was, of Asian historical development for centuries at a time.

The dawn of the modern world turned upside down the traditional disparity between Japan and China. Indeed, what the Chinese continue to call their “century of humiliation,” from the Opium War of 1839 to the victory of the Chinese Communist Party in 1949, was largely contemporaneous with Japan’s emergence as the world’s first major non-Western power. As the centuries-old Qing dynasty and China’s millennia-old imperial system fell apart, Japan forged itself into a modern nation-state that would inflict military defeats on two of the greatest empires of the day, China itself in 1895 and czarist Russia a decade later. Japan’s catastrophic decision to invade Manchuria in the 1930s and fight both the United States and other European powers resulted in devastation throughout Asia. Yet even as China descended into decades of warlordism following the 1911 Revolution, and then the civil war between Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists and Mao Zedong’s Communists, Japan emerged from the vastation of 1945 to become the world’s second-largest economy.

Since 1990, however, the tide has reversed, and China has come to occupy an even more dominant global position than Tokyo could have imagined at the height of its postwar prominence. If international power can crudely be conceived of as a three-legged stool, comprising political influence, economic dynamism and military strength, then Japan only fully developed its economic potential after World War II, and even then lost its position after a few decades. Beijing, meanwhile, has come to dominate international political fora while building the world’s second most powerful military, and becoming the largest trading partner of over one hundred nations around the globe.

Yet in comparative terms, both China and Japan today are wealthy, powerful nations. Despite nearly a generation of economic doldrums, Japan remains the world’s third-largest economy. It also spends roughly $50 billion per year on its military, boasting one of the world’s most advanced and well-trained defense forces. On the continent, with its audacious Belt and Road Initiative, free-trade proposals and growing military reach, China is widely considered the world’s second most powerful nation, after the United States. This rough parity is new in Japan-China relations, and has been perhaps the single greatest, if often unacknowledged, factor in their contemporary relationship. It is also the spur for the intense competition the two are waging in Asia.