China vs. Japan: Asia's Other Great Game

Beijing and Tokyo will undoubtedly compete long after U.S. foreign policy has evolved.

INCREASINGLY, CHINESE and Japanese foreign policies in Asia appear to be aimed at countering the influence—or blocking the goals—of each other. This competitive approach is taking place in the context of the deep economic interactions noted above, as well as the surface cordiality of regular diplomatic exchanges. In fact, one of the more direct clashes is taking place over regional trade and investment.

With its head start on economic modernization and postwar political alliance with the United States, Japan helped shape Asia’s nascent economic institutions and agreements. The Manila-based Asian Development Bank (ADB), founded in 1966, has always been led by a Japanese president, working closely with the American-dominated World Bank. The two institutions set most of the standards for lending to sovereign states, including expectations for political reform and broad national development. In addition to the ADB, Japan also expended hundreds of billions of dollars of official development assistance (ODA), starting in 1954. By 2003, it had disbursed $221 billion worth of aid globally, and in 2014, it still budgeted approximately $7 billion of ODA globally; $3.7 billion of this amount was spent in East and South Asia, mostly in Southeast Asia, and particularly in Myanmar. The political scientists Barbara Stallings and Eun Mee Kim have observed that overall, more than 60 percent of Japan’s overseas aid goes to East, South and Central Asia. Japanese assistance has traditionally been targeted for infrastructure development, water supply and sanitation, public health and human-resources development.

In contrast, China’s institutional initiatives and aid assistance traditionally lagged far behind Japan’s, even though it too began providing overseas aid in the 1950s. Scholars have noted that it has been difficult to evaluate China’s development assistance in part because of the overlap with commercial transactions with foreign countries. Moreover, over half of China’s aid goes to sub-Saharan Africa, with only 30 percent going to East, South and Central Asia.

In recent years, Beijing has begun to increase its activity in both spheres, as part of a comprehensive regional foreign policy. Perhaps most notable has been China’s recent attempts to diversify Asia’s regional financial architecture by establishing the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Proposed in 2013, the AIIB formally opened in January 2016 and soon attracted participation from nearly every state, except Japan and the United States. The AIIB explicitly sought to “democratize” the regional lending process, as Beijing had long complained about the rigidity of the ADB’s rules and governance, which gave China under 7 percent of the total voting share, compared to over 15 percent for both Japan and the United States. Ensuring China’s dominant position, Beijing holds 32 percent of AIIB’s shares, with 27.5 percent of the voting power; the next-largest shareholder is India, with just 9 percent of shares and just over 8 percent of the voting power. Compared to the ADB’s asset base of approximately $160 billion and $30 billion in loans, however, the AIIB has a long way to go in reaching a size commensurate with its ambitions. It was initially capitalized at $100 billion, but only $9 billion of the that so far has been paid in—$20 billion is the goal. Given its initially small base, the AIIB disbursed only $1.7 billion in loans its first year, with $2 billion slated for 2017.

For many in Asia the apparent aid and finance rivalry between China and Japan is welcome. Officials from countries that desperately need infrastructure, such as Indonesia, hope that there will be a virtuous cycle in the ADB-AIIB competition, with Japan’s high social and environmental standards helping to improve the quality of China’s loans, and China’s lower-cost structure making projects more affordable. With an estimated need for $26 trillion in infrastructure development by 2030, according to the ADB, the more sources of financing and aid the better, even if Tokyo and Beijing view both financial institutions as tools for larger goals.

Chinese president Xi Jinping has pegged the AIIB to his ambitious, some would say grandiose, Belt and Road Initiative, essentially turning the new bank into an infrastructure-lending facility along with the older China Development Bank and the newer Silk Road Fund. In comparison to Japan, China has focused the majority of its overseas aid on infrastructure, and the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) serves as the latest, and largest incarnation of that priority. It is the BRI, also known as the “new Silk Road,” that represents one of the key challenges to Japan’s economic presence in Asia. At the inaugural Belt and Road Forum, held in Beijing in May 2017, Xi pledged $1 trillion of infrastructure investment spanning Eurasia and beyond, essentially attempting to link land- and sea-based trading routes in a new global economic architecture. Copying a page from the ADB, Xi also promised that the BRI would seek to reduce poverty around Asia and the world. Despite widespread suspicion that the amounts ultimately invested in the BRI would be significantly less than promised, Xi’s scheme represents as much a political program as an economic one.

Functioning as a quasi-trade agreement, the BRI also highlights the free trade competition between Tokyo and Beijing. Despite what many consider a timid and sluggish trade policy, Japanese economist Kiyoshi Kojima had actually proposed a “Free Trade Area of the Asia-Pacific” as far back as 1966, although the idea was not taken seriously until the mid-2000s, by the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum. In 2003, Japan and the ten-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) began negotiating a free-trade agreement, which came into effect in 2008.

Japan’s major free-trade push came with the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), which it formally joined in 2013. Linking Japan with the United States and ten other Pacific nations, the TPP would have accounted for nearly 40 percent of global output and fully a quarter of global trade. However, with the United States withdrawing from the TPP in January 2017, the pact’s future has been thrown into doubt. Prime Minister Abe has been loath to renegotiate the pact, given the political capital he spent on getting it passed in spite of agricultural-lobby opposition. For Japan, the TPP still remains the germ of a larger community of interests based on enhanced trade and investment, and adoption of common regulatory schemes.

China has sought over the last decade to catch up with Japan on the trade front, signing its own FTA with ASEAN in 2010, and updating it in 2015, with the goal of reaching two-way trade totaling $1 trillion and investment of $150 billion by 2020. More significantly, China has adopted a 2011 ASEAN initiative, the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), which would link the ten ASEAN nations with their six dialogue partners: China, Japan, South Korea, India, Australia and New Zealand. Accounting for nearly 40 percent of global output, and linking close to 3.5 billion people, the RCEP increasingly has come to be seen as China’s alternative to TPP. While Japan and Australia in particular have sought to slow final agreement over RCEP, Beijing has been given a huge boost by the Trump administration’s withdrawal from TPP, and the widespread impression that China is now the global economic leader. Tokyo is finding little success in combating such opinion, yet continues to try to offer alternatives to China-dominated economic initiatives. One such approach is to remain engaged in RCEP negotiations, and another is to have the ADB co-fund certain projects with the AIIB. This type of cooperative competition between Japan and China may become the norm in regional economic relations, even as each seeks to maximize its influence in both institutions and with Asian states.

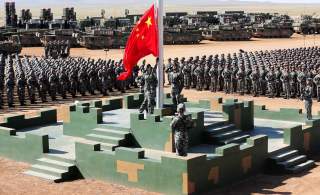

On security matters, there is a far more direct struggle for influence and power in Asia between Beijing and Tokyo. This may sound odd when applied to Japan, which is well-known for its pacifist society and the various restrictions on its military, but the past decade has seen both China and Japan seek to break out of traditional security patterns. Beijing is focused on the United States, which it sees as a major threat to its freedom of action in the Asia-Pacific region. But observers should not dismiss the degree to which Chinese policymakers and analysts worry about Japan, in some cases considering it an even bigger threat than America.

Neither Japan nor China has any real allies in Asia, a fact often overlooked when discussing their regional foreign policies. They dominate, or have the potential to dominate, their smaller neighbors, making it difficult to create bonds of trust. Moreover, memories of each as an imperial power are well remembered in Asia, adding another layer of often-unspoken wariness.

For Japan, this distrust has been abetted by its fraught attempts to deal with the legacy of the Second World War, and the sense on the part of most Asian nations that it has not sufficiently apologized for its wartime aggression and atrocities. Yet Japan’s long-standing pacifist constitution and limited military presence in Asia after 1945 helped tamp down suspicions of its intentions. Since the 1970s, Tokyo has prioritized building ties with Southeast Asia, though until recently those were primarily focused on trade.